Online platforms have created an open space that facilitates communications of different cultures and the exchange of different opinions among users, but they have also led to an exponential growth of hate speech, which increases the harm to target groups (Citron, 2011). However, hate speech is a concept that is intertwined with political, philosophical, ethical, and sociocultural issues and is constantly being defined. It changes according to social contexts, history, and cultural values are tolerated differently in different social contexts and have not been uniformly defined. As an active actor, the state has produced and delineated the range of acceptable public speech, defining what is speakable and unspeakable (Butler, 1997). While The balance between defining and limiting hate speech, and protecting the right to freedom of expression on online platforms has always been a challenge (Flew, 2021). The difficulty of addressing this issue is compounded by differences in national laws and international treaty regimes.

This essay discusses the reasons for the difficulties in managing online hate speech, analyzes the potential radicalization of gender antagonism and misogyny by unclear hate speech boundaries through a case study: the recent P&G article regarded insults to women, and reflects on future measures that should be taken by states and platforms to improve hate speech governance.

Difficulties of Online Hate Speech Governance

The Internet no longer applies to single state regulation. The dominance of cyberhate governance has shifted from the state to individual Internet technology companies. Most platforms define hate speech based on its universal definition, but there are differences in the specific content restrictions. For example: In the case of protected gender, Facebook (2021) explicitly defines derogatory terms related to gender and expressions that are better or worse than a protected characteristic as hate speech, and gives specific examples for reference, such as “I believe that males are superior to females”. While Twitter only states that sexist content is prohibited, but does not have any further information. These discrepancies led to different perceptions of hate speech, different expectations of hate speech governance, and an inability to reach agreed-upon standards and norms. A survey on hate speech tolerance in 2017 shows that 82% of Americans said people have difficulty agreeing on a definition of hate speech (Ekins, 2017).

Internet companies with slower or less proactive technological development and management responses are seen more as irresponsible and guilty entities, from flagging and reporting tools, to word and link filters and blacklists. These mechanisms are inherently limited, as they leave little space for clear and open discussion of why something is considered offensive (Crawford and Gillespie, 2016). Machines can immediately identify copyrighted or banned material (eg: pornography) but are far less capable of distinguishing between content that is offensive or malicious to people than humans (Murgia and Warrell, 2017). Yet hate speech on the Internet is wrapped in a sea of massive, anonymous, border-crossing Internet content that simultaneously takes on a multilingual, multiform appearance and combines emojis, images, audio, and video, with content that is increasingly obscure, abstract, and symbolic, and it is thought impossible for humans to keep up with the diversity of content and the speed at which it appears.

Controversial Article Posted by P&G

In the absence of a clear definition of the boundaries of online hate speech, gender equality remains a distant goal while more and more people recognize the importance of gender identity, and gender-based violence, hate speech, and disinformation are widely used online and offline to chill or kill women’s expression (Khan, 2021).

On March 13, P&G published a controversial article on its official account “P&G Member Center” titled “Do women’s feet smell 5 times worse than men’s? If you don’t believe it, smell it”. In the article, P&G created a comparison between men and women and pointed out “women’s dirty” through several misleading subheadings in the form of scientific truths. The content of the advertisement includes: Women often don’t wear socks, which turns their shoes into a veritable sauna which makes their feet stink; The stink is due to the fact that women’s feet contain six times more bacteria than men’s; Women’s chest areas smell worse than men’s, that their hair is twice as dirty due to infrequent washing, and that their underwear is dirtier on average——even for women who pay close attention to personal hygiene.

Ironically, the purpose of the article was just to recommend its own line of women’s wash products. When the article came out, it caused dissatisfaction and boycott from the majority of female users, who said that personal hygiene has nothing to do with men and women and that the content of this P&G ad was insulting and offensive to women, and was deliberately creating a comparison between men and women and selling anxiety.

The article was immediately reposted to Weibo, and the hashtag “P&G was Charged with insulting Women” hit the headline. Further causing cross-platform hate speech. Weibo completely turned into a battlefield of gender antagonism. Some male users thought the article was a popular science article with a scientific basis, the overreaction of female users precisely illustrated the odiferous of feminism. Some of them even said, “It’s a fact that women stink, and it’s useless for you to defend yourselves”. And some female users also hit back at all men, “Men are the ones who stink”.

It is important to note that in the P&G article, to highlight their “scientific”, the conclusion claims that men’s foot bacteria reproduction rate is 400%, women’s is 2300%. However, we cannot find an authoritative data source, any endorsement from professional academic journals, or a sufficient data sample for this conclusion. But Phillip (2021), a Neurologist mentioned something related: males and females has the same number of sweat glands. However, males secrete approximately five times the size and volume of each gland than females.

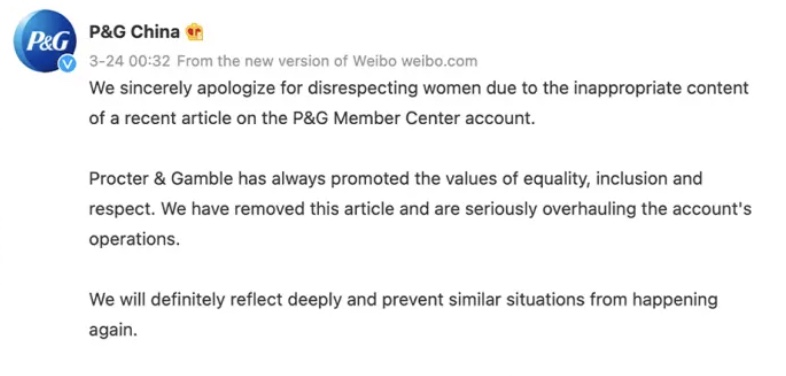

After an outcry, P&G removed the article and issued a public apology for the inappropriate content of the article that was disrespectful to women. They promised that they would seriously overhaul the account’s operations and certainly reflect deeply and prevent similar situations from happening again.

Whether the Content of the Article Constitutes Online Hate Speech?

The International Network Against Cyber Hate(2019) explicitly categorizes “misogyny” among the seven types of hate speech, but there is little division between the concepts of misogyny and sexism. Sexism has the following characteristic: it has a probative component, providing reasons to believe that men are inherently superior to women. (Richardson-Self, 2018). Obviously, the description of women as “dirtier” than men in the entire P&G article is a reflection of this characteristic.

The P&G article itself may not be directly defined as misogynistic, but it has intentionally or unintentionally created gender antagonism. Sexism does not absolutely mean antagonism or hostility, it can be used to serve misogynistic purposes. (Manne, 2017). As in the case of the Weibo comments attacking women, when some men directly cite the “scientific basis” of the article to further insult women and show direct hostility. The article has become a weapon of misogynistic speech.

The article is actually the edge-ball of misogyny and hates speech in the guise of “science”. Misogyny is seen as a more deeply rooted and violent expression of sexism. But violence is not limited to overt expressions, it can also be expressed through a subtle or unconscious way of scrutinizing and regulating women (Savigny, 2020). The article ignored the possible negative effects on women (e.g., stirring up antagonism, stigmatizing women, labeling women, creating self-doubt, low self-esteem, and anxiety in some women), tried to make women believe they are dirty through derogatory terms and inaccurate information just for its marketing purposes.

Why No Platform Involvement

The ambiguity and uncertainty of the legal provisions. The platforms as third-party subjects of law enforcement, specific regulatory matters need clear legal empowerment from the state. While The concept of online hate speech is rarely used in China’s internet governance discourse system. It does not currently have a specific law on hate speech, there are only relevant provisions in laws and regulations. For example, Article 15 of Measures for Managing Internet Information Services (2000) prohibits the reproduction and dissemination of content that insults or defames others and infringes on the legitimate rights and interests of others. However, there is no certain definition of insulting speech and conducts, which brings some problems to the relevant rules of platforms.

High-speed network information dissemination with Unclear Criterions of Content Audit. In the new media environment, the high communication rate of the Internet can quickly spread public opinion information throughout the network. Weibo does not even audit content until after it has been sent, and users can search or see what is posted instantly. The emergence of hashtags and auto-push functions gives more space for hate speech to spread. In such a situation, the current methods of regulating online violence are lagging behind

The platform’s inadequate rules and audit system significantly reduce the efficiency of problem handling. In China, the content audit rules of platforms like WeChat and Weibo are not public, so it increases the difficulty of determining whether specific content is offensive.

As for the auditing mechanism, the algorithmic audit can only filter specific sensitive content (politically exposed people, pornography, violence, etc.) for processing in the first step, so the platforms rely more on users to report hate content that needs to be judged and processed further by the content moderator in most cases(Zhang and Mao, 2021) The “notice and delete” rule cannot completely stop the spread of online violence because the speed of uploading of inappropriate information is much faster than identifying and deleting of it. Therefore, even if online violence is finally removed, it does not have the effect of clarifying the facts and cleaning up the online space.

Conclusion and Reflection

Hate speech has broken through time and space to become a global problem. In the reality of the increasing proliferation of hate on the Internet, instead of the state and government, internet technology companies have become the active and main role in regulating hate speech. They are at the crossroads where they must take responsibility for avoiding risk, promoting values and responsibility, identifying the nature of hate speech, and guiding users to self-regulate. While there is no industry consensus on how to regulate hate speech. On this basis, the big tech companies must serve as models. They need to define hate speech in their rules and regulations in order to identify and regulate it.

At the technical level, Platforms need to continuously improve the rules and logic of machine auditing, and constantly improve the internal auditing rules of platforms so that they can accumulate enough data and enable machines to provide more accurate identification of hate speech.

While only relying on the autonomy of the platforms, spontaneous moral supervision and resistance to hate speech are not enough. Maintaining network security and creating a good international information dissemination environment requires the joint efforts of the international community as hate speech transcends national borders(He and Jiang, 2018). The regulation of hate speech should be agreed upon at the international level, and special laws should be enacted to regulate it, which is definitely a long way to go in the face of the different realities of global history, culture, and ideology.

References

Buttler. J. (1997). Sovereign Performatives in the Contemporary Scene of Utterance[J]. Critical Inquiry, 23 (2): 350-377.

Cost. B, (2022). P&G claimed women’s feet are ‘5 times’ stinkier than men’s but they regret it. New York Post. https://nypost.com/2022/03/29/procter-gamble-retracts-advert-claiming-that-women-smell-worse-than-men/

Crawford, K., & Gillespie, T. (2016). What is a flag for? Social media reporting tools and the vocabulary of complaints. New Media & Society, 18(3), 410-428. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2476464

Citron, D. K., & Norton, H. (2011). Intermediaries and hate speech: Fostering digital citizenship for our information age. BUL Rev, 91, 1435. https://scholar.law.colorado.edu/articles/178/

Ekins, E. (2017). 82% Say It’s Hard to Ban Hate Speech Because People Can’t Agree What Speech Is Hateful. Cato Institute. https://www.cato.org/blog/82-say-its-hard-ban-hate-speech-because-people-cant-agree-what-speech-hateful

Facebook. (2021). Community Standards Enforcement Report. https://transparency.fb.com/zh-cn/policies/community-standards/hate-speech/

Inach. (2019). What Is Cyber Hate.chrome-extension://cdonnmffkdaoajfknoeeecmchibpmkmg/assets/pdf/web/viewer.html?file=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.inach.net%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2FWHAT-IS-CYBER-HATE-update.pdf

Khan. I. (2021). ‘Sexism and misogyny’ heightened; women’s freedoms were suppressed. United Nations. https://news.un.org/en/story/2021/10/1103382

Manne, Kate. 2017. Down girl: The logic of misogyny. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Murgia, M& Warell, H. (2017). Why tech companies struggle with hate speech. Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/2aaa13b2-1ba2-11e7-bcac-6d03d067f81f

Phillip, A. L. (2012). Primer on the Autonomic Nervous System. Cambridge: Academic Press.

Richardson-Self, L. (2018), Woman-Hating: On Misogyny, Sexism, and Hate Speech. Hypatia, 33: 256-272. https://doi.org/10.1111/hypa.12398

Savigny, H. (2020). Sexism and Misogyny. The International Encyclopedia of Gender, Media, and Communication. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119429128.iegmc092

State Coucil. (2000). Laws of the People’s Republic of China. AianLII. http://www.asianlii.org/cn/legis/cen/laws/mfmiis499/

Zhang, J& Mao, Y. R. (2021). Content Audit of Domestic Platform Media: Motivation, Current State and Breakthrough. Publishing Journal, 29(6), 76.

Twitter. (2021). The Twitter Rules. https://help.twitter.com/zh-tw/rules-and-policies/hateful-conduct-policy