Algorithms, such as the Euclidean algorithm for computing the greatest common divisor (GCD) of two integers, have traditionally been thought of as mathematical instructions for addressing specific problems. Algorithms are becoming more common in computer science as rules and processes in tasks like calculation, data processing, and automated decision-making.

Algorithmic selection is increasingly embedded in daily activities. When we consume entertainment products (news services, music, streaming video) and make purchases on Internet platforms, algorithmic recommendations and rankings play a significant part in our selections. People’s offline scenarios, such as restaurants, transportation, and housing choices, are also influenced. In addition, algorithmic selection is used in more vital decisions, including hiring, school admissions, big data policing, and criminal risk assessments in court.

Algorithms are strongly linked to our society. A massive number of data can be utilized by setting up and executing the model, introducing valuable insights and improving efficiency. However, the frequent controversies of algorithm bias and algorithm discrimination in recent years enable people to realize that algorithms are not neutral.

Algorithms do not only operate in cyberspace. If prejudice and discrimination are not addressed, marginalised groups will suffer more unfair outcomes and harm, and social justice will become an unrealistic concept.

Bias in Facial Recognition Technology

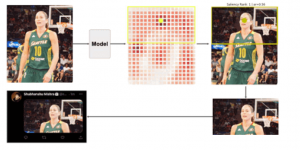

Twitter has received a lot of criticism in 2020 for racial bias in its picture-cropping algorithm. Twitter has an automatic image cropping function, which means that when a user uploads an image, Twitter automatically crops it to meet the aesthetics of the page in preview mode. This cropping does not directly shrink or centre crop the original image, but it preserves the face or other vital details by identifying its content.

According to Twitter users, pictures with headshots of Barack Obama and the U.S. Senate leader Mitch McConnell always showed the latter image in the preview pane on mobile devices (BBC News, 2020). This observation has nothing to do with the two politicians, but it demonstrates that the white face is more likely to appear in the image preview when an image contains both a black and a white face. It reflects the unfairness and the racial bias of Twitter’s facial recognition algorithm and image cropping algorithm, believing that white faces are more important and preferred than black faces. Some users also noticed that the algorithm is more likely to choose men over women in image cropping.

Twitter responded by saying the model showed no racial and gender bias during the testing phase, but they will have more analysis.

Eight months later, Twitter announced the outcomes of our bias assessment. The report states that the algorithm was trained on human eye-tracking data, which means that the saliency score of everything in the image is calculated first, and then the highest scoring region is selected as the centre of the crop.

Source: Twitter

https://blog.twitter.com/engineering/en_us/topics/insights/2021/sharing-learnings-about-our-image-cropping-algorithm

In quantitative testing, they found:

- An 8% higher demographic parity favouring women than men

- A 4% higher demographic parity favouring white individuals than black individuals.

- A 7% higher demographic parity favouring white women than black women.

- A 2% higher demographic parity favouring white men than black men.

This result confirms that the algorithm is slightly biased. Twitter internal researchers conclude that some content on Twitter is inappropriate for seeking algorithms. As a result, Twitter would remove algorithmic cropping, allowing users to choose how to crop images (Twitter, 2021).

In an algorithmic bug bounty competition, Bogdan Kulynych, a graduate student at Switzerland’s EFPL university, further pointed out that the image cropping algorithm on Twitter prefers faces that are younger, thinner, and have lighter skin (Alex Hern, 2021).

Facial recognition technology has been used today for years, but the technology is immature and is often accused of bias and discrimination. The National Institute of Standards and Technology studied 189 facial recognition algorithms, and they report that most facial recognition algorithms are biased. The results still show that for marginalized groups, such as minorities and women, the algorithm has a higher recognition error rate。

Bias in Search Engines

The media’s stereotyping of women and people of colour and its harmful consequences have been studied by many, and the public is increasingly able to identify and criticize discriminatory content. In information science, on the other hand, data and algorithms are always assumed to be objective. Ranking of information retrieval results is generally considered to be a direct effect of relevance without any manipulation and editing. Information culture is expected to be a breakthrough to eliminate social injustice. Even marginalized groups can embrace a large amount of information and alleviate information asymmetry.

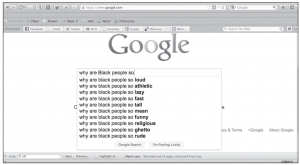

Safiya Noble challenges this perception. She documents her experience of being hit by racism and sexism in search engines. Noble searched for “black girls” in 2011, and the first page showed many porn-related results. She searched “why are black people so,” in 2013, Google autosuggest results were mostly negative, harsh adjectives. When she searched Google images for “professional style” in 2013, it turned up images of primarily white men.

“why are black people so,”

Source: Noble, S. U. (2018). Algorithms of oppression : how search engines reinforce racism.

She points out that each of these searches represents Google’s algorithmic conceptualizations of various persons and concepts.

Information monopolies like Google can adjust to the sorting of web search results. The user’s click, coupled with the business process that allows paid advertising to be prioritized in search results, Google’s creation algorithm can be regarded as an advertising algorithm, not an information algorithm. It also shows that the discriminatory representation of marginalized people on search engine pages corresponds to the lack of social status in the real business world. Google search narrative is more explicitly racist and sexist than that of newspapers, movies, television and other media.

Google’s users indirectly consent to or endorse the algorithm’s results by continuing to use the product. It is almost inevitable that people are encouraged or required to use such search engines and other Google products in various scenarios such as schools and businesses. Discrimination resides in algorithms and computer code, while people increasingly rely on information science technology and artificial intelligence products. Noble is deeply disappointed with digital culture, and she believes that there will also be major human rights issues in the rapidly developing artificial intelligence of the 21st century.

This blatantly discriminatory content no longer pops up on a large scale when searching for the exact keywords today. However, as a significant search engine that relies on advertising for profit, its mechanism has not been changed. Bias in data and algorithms remains, and Noble’s concerns about human rights in the internet ecosystem remain prescient.

Why are algorithms biased?

An algorithm is often considered a “black box” where users can use an algorithm without understanding its inner workings. So everyone, maybe including the programming team, finds it a challenge to analyze Biases and discrimination through algorithms.

One possible reason is that the data reflect widespread biases in history and current society. People create algorithms, and design teams may unconsciously implant their biased values. For instance, in a recruitment algorithm, historical input data shows that a specific position has recruited more men, and in subsequent recruitments, the algorithm tends to rate male candidates higher. That doesn’t mean women can’t excel in that role. The phenomenon of positive feedback can also exacerbate biases when the algorithm continues to run, making the algorithm system more extreme.

Ethnic minorities and women account for a small proportion of Internet companies and may not be sufficiently involved in algorithm design and machine learning. The training data used may not adequately represent the interests of marginalized people, and the backwardness of human society is reflected in the input link.

Companies that provide algorithmic services can profit from discrimination, such as the advertising content (even with bias) supplied by search engine companies, which is an essential source of revenue.

How to eliminate discrimination and bias in algorithms?

User and public reporting and suggestions are the first steps toward correcting algorithmic bias, from the racial and gender biases of Google’s search engine and Twitter’s auto-cropping algorithm scandal to the controversy over Apple credit card being involved in claimed gender discrimination in credit card limits. These discoveries and accusations made Internet companies and the public realize that algorithms cannot escape the long history of racial discrimination and sexism in human society.

Because the black box system will continue to exist, even the algorithmic system designers may be challenged to realize the fairness problems of the algorithm. These kinds of thinking and observations about algorithmic fairness should continue to be encouraged, which can help reduce biases caused by algorithms, intentionally or unintentionally.

With the scandal of algorithmic bias, it becomes clearer that algorithms are not neutral. At the same time, due to the controversies, Internet corporations that provide algorithmic services have been criticized, their reputation has been damaged, and it is more difficult to gain public understanding and trust. As a result, these businesses will rely more heavily on algorithm ethics and algorithm fairness in the process of providing services.

For the bias controversy in image cropping algorithms, Twitter introduced an algorithmic bias bounty competition in 2021. They found it challenging to prevent bias in machine learning (ML) models completely, so they turned to the contestants for assistance in correcting evident biases in their image cropping algorithms (Twitter, 2021). Bogdan Kulynych, who investigates that the algorithm valued slimmer and lighter faces, is the competition’s winner. This bounty competition could be regarded as a public relations stunt, but it also demonstrates its concern for machine learning ethics and willingness to address algorithmic biases.

Internet companies should form a diverse algorithm design team and allow people from different backgrounds to participate in machine learning to introduce more varied viewpoints and avoid bias caused by the limitations of training data.

Business, academic, and civil society actors are taking action to address this technical-level bias, discussing fair computing models, with Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency in Machine Learning (FATML) workshops being an example. Scholars have also begun to link algorithmic models of fairness to philosophical theories of political and economic equality (Heidari, Loi, Gummadi, & Krause, 2018; as cited in Stark, Greene, & Hoffmann, 2020).

When we look at the discussions on algorithms and AI, people-oriented is the cornerstone of algorithm governance carried out by various international organisations through tools and principles, and fairness and diversity in the algorithm are stressed.

For example, in The OECD Artificial Intelligence (AI) Principles, the first principle recognizes that algorithmic systems AI systems may perpetuate existing societal biases and disproportionately affect vulnerable populations, such as minorities, women, children, elderly people etc. This principle emphasizes that AI can and should also be used to empower all members of society and help reduce bias (OECD, 2019).

In the EU’s High-level expert group on the artificial intelligence (AI HLEG) project, experts emphasized that the application of algorithms should comply with ethical principles and respect the fundamental rights of citizens, including marginalized groups. “Diversity, non-discrimination and fairness” as one of the seven principles, recommends the establishment of a diverse design team, stipulates that the AI system should be protected from bias during development, and consult stakeholders throughout the life cycle of the AI system to strengthen civic participation (European Commission, 2019).

Reference List:

European Commission (2019). Communication: Building Trust in Human-Centric Artificial Intelligence. https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/communication-building-trust-human-centric-artificial-intelligence

Ferguson, A. G. (2017). The rise of big data policing : surveillance, race, and the future of law enforcement. New York: New York University Press.

Grother,P., Ngan, M.& Hanaoka Ka. (2019). Face Recognition Vendor Test (FRVT) Part 3: Demographic Effects

https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/ir/2019/NIST.IR.8280.pdf

Noble, S. U. (2018). Algorithms of oppression : how search engines reinforce racism. New York: New York University Press.

OECD (2019). The OECD Artificial Intelligence Principles. https://oecd.ai/en/ai-principles

Stark, L., Greene, D., & Hoffmann, A. L. (2020). Critical Perspectives on Governance Mechanisms for AI/ML Systems. In The Cultural Life of Machine Learning (pp. 257–280). Cham: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-56286-1_9

Van Giffen, B., Herhausen, D., & Fahse, T. (2022). Overcoming the pitfalls and perils of algorithms: A classification of machine learning biases and mitigation methods. Journal of Business Research, 144, 93–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.01.076