Introduction

With the popularity of social media, recording and presenting self-culture is gradually becoming a contemporary habit. Advances in algorithmic recommendations and artificial intelligence technology have made more and more people willing to use social media to get the fastest information. However, along with this, social media platforms disseminate information about women’s bodies and appearance in different ways, influencing their evaluation of their bodies and leading to anxiety and desperate pursuit of women’s appearance. Moreover, algorithmic bias amplifies social male perceptions of beauty and scrutiny of women, all of which exacerbate women’s anxiety about their external body image. Social reality is now increasingly shaped and framed by algorithmic choices in various spheres of life on media platforms. (Just & Latzer, 2017) These influence society’s aesthetic ideologies and the limits of women’s self-perceptions. On the one hand, the distorted personalised aesthetic values shaped by filter bubbles are suspected of inducing and exacerbating women’s mental health problems. On the other hand, personalised filter bubbles in social media contribute to the homogenisation of audiences’ aesthetic consciousness, immersing them in a single bubble of personal values. This can lead to reinforcing extremism, causing polarisation. Therefore, this blog will use the Instagram platform as an example to discuss personalised aesthetics distorted by social media. The blog will focus on how filtering bubbles and algorithmic recommendations can trigger anxiety about women’s appearance and shape users’ perceptions of beauty. Furthermore, suggestions will be made for the regulation and governance of the present algorithmic disruption.

The aesthetic “shaping” of women by Instagram’s beauty filters

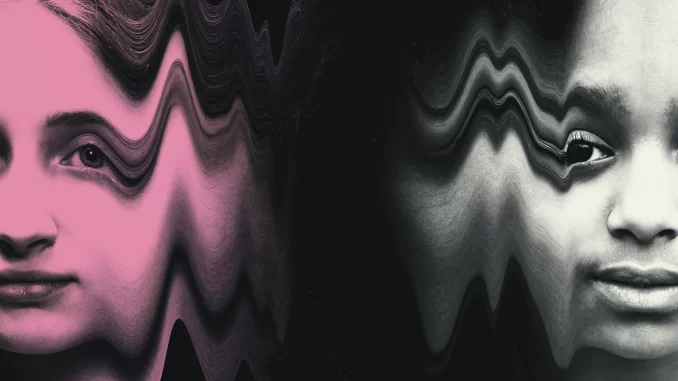

Beauty filters are a product of both social and artificial intelligence technology and, with their emergence, set a whole new aesthetic value for the younger generation. Instagram is one of the most popular and fastest growing social media platforms. It brings a new social experience, interacting with other users by sharing photos and videos. Instagram allows users to take a photo with their smartphone and then add different filter effects to the original photo, which is then shared on social networks. It is because of Instagram’s high quality filter function that it has become a popular filter for the aesthetic trend of the times. Users can adjust the data of the beauty filters, and as the range of adjustable parameters expands, a wide variety of styles of photos emerge on the platform, influenced by the aesthetics of different users. In Instagram’s beauty filters, users can find a wide range of make-up, hairstyles, noses, eyes, mouths, etc. The real subject can be freely and digitally adjusted, allowing the appearance to be transformed to meet the needs of the user. Furthermore, even the hardiest users are tempted to try out filters to smooth the skin, fill in the lips, or enhance the jawline and cheekbones. The decline in user self-esteem interacts with the growing fascination with Instagram filters. A large number of women want to fit into the beauty mode of these facial adjustment and retouching apps to adjust their appearance. (Hamdy, 2022) However, when the platform is flooded with filters creating overly embellished images, it indicates that users have become immersed in a fantasy of their own making, confusing reality with imagination. In 2019, Instagram announced the complete removal of plastic surgery selfie filters. Officials claim to guard the mental health of teenagers and to avoid aesthetic misinformation about plastic surgery filters. But has this solved the problem? The answer is obvious. Use the Fix Me filter and the Plastic filter as examples.

– The Fix Me filter shows the doctor’s dashed markings before the plastic surgery. For example, the “plastic” area is marked with a dotted line, and arrows and notes are used to indicate how the changes are to be made. This filter also adds bruises to the subject’s face to show the recovery period of plastic surgery.

– The Plastic filter gives the subject a more defined and deeper face, with higher cheekbones and fuller lips to show the results of plastic surgery.

Two years later, when we try to search for related Plastic filters on Instagram, we find that related filter themes still exist. The Pillow face filter, for example, shows the look that can occur after excessive Botox and plastic surgery. The new aesthetic standards spread by Instagram act to varying degrees of appearance anxiety among young and middle-aged women, and these so-called aesthetic standards bring with them a great deal of psychological pressure and negative self-evaluation. However, personal aesthetics are not only shaped by the platform’s beauty filters but also by the filter bubbles and algorithmic recommendations behind social media.

Narrow and homogenised aesthetic perceptions due to personalised bubbles

In the age of algorithms, people can be matched to exactly the information they need and prefer. Instagram’s personalised recommendations for streams determine how photos and videos are recommended based on the likelihood that the user is interested in the content or depending on the type of accounts and posts the user interacts with most frequently daily. Eli Pariser spoke at TED in 2011 on Beware online “filter bubbles”. He refers to ‘filter bubbles’, where algorithmic recommendations filter out heterogeneous information and create a personalised world of information for users, placing them in a ‘web bubble’. (Pariser, 2012) This illustrates how users surrounded by filtered bubbles are isolated from the exchange of diverse perspectives. Even though social media enables users to access diverse information, it is associated with increased social polarisation. (Chitra & Musco, 2020) Take the explore feature of Instagram as an example. When users search for content related to beauty, the platform will continuously recommend relevant content based on the user’s search content through a continuous cycle of filter bubbles. The explore page presents photos and images tailored to the user’s needs. Typically, these photos and images may be celebrities or social influencers showing off their flawless appearance and perfect bodies. Research has shown that Instagram use is positively correlated with self-vilification among young women. This relationship arises from the internalisation of social beauty ideals and comparisons of appearance with celebrities on Instagram. (Fardouly et al., 2017) Such an aesthetic value system constantly puts pressure on young people who do not conform to the standards to continuously self-examine their own bodies. The original individuality of the body dissolves under the pressure of aesthetic standards and is framed under an overly perfect, unrealistic standard of beauty. On the one hand, Instagram’s personalised recommendations are subliminally shaping the environment in which users receive information, leading to an inherent reinforcement of value identities. Also, the filter bubble distorts the audience’s understanding of the world, slowly losing the ability to think and judge for themselves. This can lead to the narrowing and homogenisation of individual aesthetic values and can easily create a vicious circle. With more users following content from attractive social influencers in algorithmic recommendation mechanisms, these images get higher engagement and therefore, they are shown to more people. Ultimately, the social bubble is not a direct cause of the posts shown to you. It is also an indirect factor.

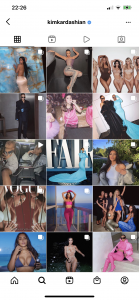

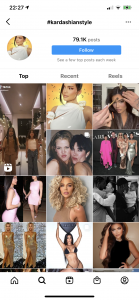

On the other hand, influencers have shaped the definition of ‘beauty’ within the business model through their own influence and discourse, which they continue to replicate and spread. Fisher (2020) points out the fundamental flaw in the Instagram platform itself, which is a carefully orchestrated traffic contest. The most viewed, liked and shared content on the platform is more likely to be pushed to the top of the platform’s public community. In the promotion of the platform, the definition of influencers and celebrity aesthetics is internalised, and the single aesthetic trait is not only deepened but increasingly, the Influencer standard is solidified in the public aesthetic perspective. As a ‘best’ criterion, the Influencer’s facial features are easy to debate and imitate. In the case of Kim Kardashian’s Instagram posts, her outfits, her hair and make-up style have become a worldwide trend to emulate. The hashtag #Kardashianstyle# can even be searched on Instagram, where most of the content is a parody of Kardashian’s ‘hourglass’ figure and style of make-up. The monolithic aesthetic culture of the influencer era is a symbiosis between the aesthetic narrowness of society and the prejudice against women. Since the new media era is also the era of the attention economy, the attention of users is an important resource that the major social media platforms are competing for. In the attention economy, filter bubbles help search engines, websites and platforms to achieve their goals in order to maximise users’ time online. But on the back of filter bubbles and personalised recommendations is the exploitation of consumers’ implicit gender bias and the self-objectification of women for the sake of desire and vanity. It causes them to have their personal aesthetic values distorted by social media.

Suggestions for regulation and governance of algorithmic chaos

In response to the algorithmic chaos that has emerged in social media, I will discuss how to regulate and govern the algorithms in social media from three perspectives: government, platforms and users.

- As a government, we should adopt laws and regulations to regulate the use of business and technology. Structure the Internet market to regulate the content and platform governance laws and regulations, rectify the advertising of aesthetic values, influencer aesthetic is not the only aesthetic standards, encourage the platform to develop a diverse aesthetic approach.

- The platform has the best understanding of how the algorithm works. The algorithm development platform first needs to consciously carry out internal constraints based on complying with the ethical norms of the algorithm. Just & Latzer (2017) suggest that corporate platforms should be required to fully demonstrate the legitimacy of personalised forms of algorithmic governance, requiring co-evolutionary interactions with algorithmic governance and providing solutions through algorithmic design approaches. In 2020, a model Nyome Nicholas-Williams launched the Black community image censorship campaign after discovering that when she posted normal personal photos of herself on the platform, they were immediately flagged by Instagram as unsuitable for viewing because they contained “nudity or sexuality “. The colourism and obesity discrimination brought about by algorithmic bias was exposed by users in this incident, and Instagram CEO Adam Mosseri promised at the time to do a better job of censoring the bodies of plus-size black women. Furthermore, it said the company would provide better user service for underrepresented groups in four areas, including addressing algorithmic bias. (Are, 2020) Algorithmic bias and discrimination can be reduced in content review by increasing human review methods in social media.

- Self-monitoring by users. As social media users, it is essential not to be limited by algorithms in terms of self-values and aesthetic values. Firstly, think about how often you receive the same type of information when using social media, how long you receive it, ask yourself if you need it and reflect on whether it is influential. Secondly, to look critically at algorithms, avoid the domestication of technology and develop a pluralistic aesthetic. Finally, self-appreciation and self-affirmation. Self-appreciation is the beginning of establishing the right aesthetic values.

Conclusion

The use of algorithms allows social users to precisely match information on needs and preferences. However, algorithms are limited to filtering and summarising users’ past behaviour so that people’s future orientation is limited and their rationality is gradually lost. The regulation of technical and ethical values behind digital beauty technology and algorithmic recommendations is still under constant revision and practice. The social prejudices and distortions of aesthetic values brought about by technology require not only social regulation but also an awakening of female consciousness. This is because these issues are closely related to social conflicts and emotional structures. On the one hand, audiences need to learn self-affirmation to respect their bodies and looks. On the other hand, media platforms should also think carefully about whether publishing content has a negative effect and create a better media ecology through the efforts of all parties to establish diverse aesthetic values. It is unrealistic to rely on a single entity to solve the risks of an algorithmic society. In the future, the governance of algorithms will also require the joint participation of multiple entities and levels of regulation.

References List

Are, C. (2020). How Instagram’s algorithm is censoring women and vulnerable users but helping online abusers. Feminist Media Studies, 20(5), 741-744. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2020.1783805

Chitra, U., & Musco, C. (2020). Analyzing the Impact of Filter Bubbles on Social Network Polarization. Proceedings Of The 13Th International Conference On Web Search And Data Mining. https://doi.org/10.1145/3336191.3371825

Fardouly, J., Willburger, B., & Vartanian, L. (2017). Instagram use and young women’s body image concerns and self-objectification: Testing mediational pathways. New Media &Amp; Society, 20(4), 1380-1395. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444817694499

Fisher, T. (2020). The smooth life: Instagram as a platform of control. Virtual Creativity, 10(1), 93-103. https://doi.org/10.1386/vcr_00022_7

Hamdy, R. (2022). How Instagram Filters are Changing Our Perception of Beauty. EgyptToday [Blog post].Retrieved 10 April 2022, from https://www.egypttoday.com/Article/6/99247/How-Instagram-Filters-are-Changing-Our-Perception-of-Beauty.

https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/tech/tech-bytes/instagram-officially-discontinues-standalone-igtv-app/articleshow/89936237.cms. (2022). [Image]. Retrieved 10 April 2022, from.

Just, N., & Latzer, M. (2016). Governance by algorithms: reality construction by algorithmic selection on the Internet. Media, Culture &Amp; Society, 39(2), 238-258. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443716643157

Mooney, D. (2022). FixMe filter [Image]. Retrieved 10 April 2022, from https://www.bbc.com/news/business-50152053.

Pariser, E. (2011). The filter bubble. Tantor Media, Inc.

WONG, J. (2022). Beauty Filters [Image]. Retrieved 10 April 2022, from https://www.technologyreview.com/2021/04/02/1021635/beauty-filters-young-girls-augmented-reality-social-media/.