Introduction

It goes without saying that algorithms are becoming increasingly common in our daily lives. They dictate the political advertisements we see on our Facebook newsfeed, suggest artists on Spotify, and can even calculate and predict one’s credit risk by analysing an individual’s data. While the availability of large data sets affords a sense of optimisation, these complex systems can be biased and discriminatory based on who trains them and how they are used (Just & Lazter, 2017).

Disentangling how these algorithmic biases come to be is not an easy task, especially due to the lack of transparency and accountability by firms. As a result, we are met with a social reality that is immersed in deep marginalisation and disillusionment.

Algorithms and Algorithmic Bias, Explained

Prior to the inception of algorithms, humans and organisations took to the liberty of making decisions and drawing conclusions in the fields of criminal sentencing, hiring and admissions. These decisions were often governed by local, state and federal laws which guided and regulated the decision-making process in terms of fairness, transparency and accountability (Kossow et al., 2021).

Fast forward to the Network society, some of these decisions are entirely made or influenced by algorithms, whose performance is acknowledged, praised and scrutinised in various contexts (Musiani, 2013). In its most basic form, an algorithm refers to a set of rules and processes used to solve a problem or complete a task, such as calculation, data processing and automated reasoning (Just & Lazter, 2017; Gwaga & Koene, 2018). Created through “mathematical and engineering repetition, trial and error, discussion and negotiation”, algorithms make predictions, determine knowledge and present it in ways that are both digestible and consumable by users (Gwaga & Koene, 2018, p.4). Some notable examples of automated culture include the selection of television shows and film via recommender systems, the choice of services and products in online stores, and the selection of online news via search engines and news aggregators (Andrejevic, 2019).

To this end, algorithms are often incredibly useful tools used to deliver accurate outputs, accomplish tasks, and offer optimisation. They are invisible aids, augmenting our lives in innovative, exciting ways. Yet, as Just & Lazter argue (2017), while the growing societal significance and potential benefits of automated decision-making are vast, public narratives and research tends to focus on the considerable risk and unrealistic expectations of these innovative technologies.

Indeed, as highlighted by Chander (2017), there is growing concern that algorithms discriminate on illegitimate grounds, such as race, gender or sex. This of course is detrimental to the social fabric of any given society, as it reinforces existing power structures, social inequities, and allows autonomous actors with power to further economic and political interests on an individual, public and collective level (Just & Lazter, 2017, p.245). For example, in 2019, researchers from the University of California, Berkeley, discovered a problem with an algorithm that was being used to allocate care to 200 million patients in the US, which resulted in black patients receiving a lower standard of care. The issue occurred as the system was allocating “risk values”, using the predicted cost of healthcare as a determining variable (Logically, 2019). Ultimately, because black patients were generally perceived as being less able to pay for the higher standard of care, the algorithm learned and determined that they were not qualified for such a standard (Logically, 2019).

In this case, the automated decision as examined above is known as bias, which typically carries negative connotations, but is more ambiguous when it is about algorithmic bias. In its most simple terms, algorithmic bias is a “systematic deviation” in an algorithm, output, performance or impact, relative to a norm or standard (Danks & London, 2019, p.2). Depending on the standard or normative used, algorithms can be morally, statistically or socially biased, and can severely impact individuals and groups (Danks & London, 2019). Accordingly, algorithmic bias is particularly concerning for autonomous systems, as they do not actively or passively involve human/s who can “detect and compensate ” for biases in the algorithm (Danks & London, 2017, p.2) . Furthermore, as algorithms become more complex through training different data, it can become difficult to understand how these systems program and arrive at their decisions. Nonetheless, disentangling the different means in which an algorithm can come to be biased will be analysed and examined below.

Factors Causing Algorithmic Bias

In consideration of the above, we now turn to the question, how and why does algorithmic bias occur? Given the complexity of this phenomenon, this analysis cannot be exhaustive, and rather will focus on two factors, that is, historical bias and discrimination, and the white male patriarchy.

Historical Bias and Discrimination

Historical and existing human biases can be embedded in training data (Fazelpour & Danks, 2017). These algorithms are created as a result of biased samples given within a dataset, which may be narrow due to negligence, or because data scientists working on the training process are prejudicial themselves (Serwin & Perkins, 2018). If left unchecked, biased and discriminatory algorithms can foster decisions which can have a widespread impact on individuals and groups.

For example, in 2019, Facebook was accused of posting job advertisements, deliberately targeting men, so women or people over the age of 55 who use the social network couldn’t see them. According to the US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), the job ads were a violation of the Civil Rights Act and the Age Discrimination in Employment Act (Campbell, 2019). Before the EEOC made its ruling, the social media giant disclosed that they will no longer allow businesses to post target ads that could discriminate against users who are women, people of colour, or the elderly (Campbell, 2019).

The White Male Patriarchy

Algorithms aren’t neutral, nor random. As emphasised by Bains (2022), they are influenced by the “same white cis-male patriarchy” that permeates all levels of society. Subsequently, it is argued then that systematic oppression is in fact occurring “behind the computer screen”, as data scientists, who are largely white cis men, lack the cultural nuance to design and train data that reflects the representation of a particular individual or groups (Lee et al., 2019; Just & Latzer, 2017).

This systematic oppression can be reflected in findings of the Discriminating Systems Report (2019), which revealed that only 2.5% of Facebook’s workforce is black, while Google and Microsoft are both at 4%. These striking figures indicate that there is a bias towards employing white cis men in technology firms, which in turn fosters an intersection between “discriminatory workforces and discriminatory technology” (Weiss, 2019). Indeed, the shortcomings of diversity within technology firms ultimately allows racial and gender bias to scale and replicate in ways that deepen and justify patterns of historical discrimination, inequalities and inequities.

To understand the nuances of algorithmic bias and discrimination, we now turn to the case study of the Correctional Offender Management Profiling for Alternative Sanctions (COMPAS) algorithm.

Case Study: The COMPAS (Correctional Offender Management Profiling for Alternative Sanctions) Algorithm

Perhaps the most controversial case of algorithmic bias and discrimination is the Correctional Offender Management Profiling for Alternative Sanctions (COMPAS) algorithm. Developed by Equivant (formerly Northpointe), COMPAS is a statistically-based algorithm used by U.S. courts to assess and predict the risk that a criminal defendant will commit a crime after release (Park, 2019). In states and county’s using COMPAS, defendants are asked to fill out answers to a 137-item questionnaire.

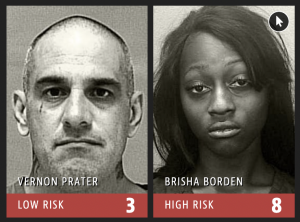

Thereafter, their answers are analysed by the software to generate predictive scores rated between 1 and 10 for factors including “rate of recidivism, risk of violence and risk of failure to appear” (Zhang & Han, 2021, p.1219). Drawing from this score, COMPAS classifies the risk of recidivism as “low-risk (1-4), medium-risk (5-7), or high risk (8-10)” (Park, 2019). This score is subsequently included in a defendant’s Presentence Investigation Report, which assists judges with determinations.

Taken on its own, the COMPAS algorithm seems somewhat reasonable, but the truth is far from reality. Indeed, in 2016, a study conducted by ProPublica revealed that COMPAS demonstrated bias in favour of white defendants, and against black defendants. Comparing the recidivism rates over a two-year period of more than 10,000 defendants in Broward County, Florida, their analysis found that black defendants were predicted to be at “higher risk” of recidivism, and were 77 percent more likely to be assigned higher risk scores than white defendants (Larson et al., 2016).

Given the biased algorithmic conceptualisations of COMPAS, it is not surprising then that the software has raised various concerns and queries among the broader social sphere (Noble, 2018). Mainly, it has raised the question, how does the software calculate its risk score? The fact of the matter is, no one really knows, aside from Equivant. Indeed, in a tell-all with TEDx Talks, Darmouth professor Dr. Hany Farid revealed that the software is a proprietary and tightly held corporate secret, which has detrimental effects on the shared social reality of historically marginalised groups (Just & Lazter, 2017; Noble, 2018). While the how remains unclear, the why comes down to the fact that algorithms are organised, trained, and produced by humans.

Accordingly, if the data itself is embedded in historical discrimination and bias, the output will be reflective of the narrow training data of the creators (Fazelpour & Danks, 2017). Viewing this through COMPAS’ lens, it is clear that the problem grows dramatically. The consequences of this algorithm means minorities will be issued risk scores at an alarming rate, which only drives groups into further inequity and marginalisation (Park, 2019). To this end, it is integral that quality assurance, training and system validation take place to ensure fairness in risk assessment algorithms. Perhaps a step further would be transparency and the right to see the allocation of data, particularly when it is used to make decisions that can have a significant impact on one’s life (Fazelpour & Danks, 2020).

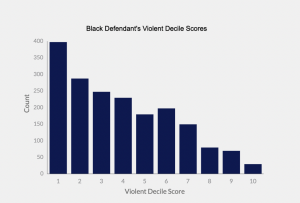

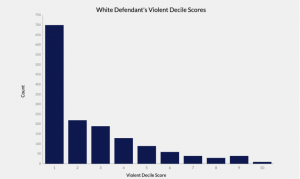

Moreover, in addition to narrow and discriminatory training data, Zhang & Han (2021) also reveal the “static” factors included in COMPAS’ algorithms which can lead to racial bias. Socioeconomic factors such as employment, education and income can impede on the risk scores of defendants (Zhang & Han, 2021). Most notably, COMPAS’s algorithms considers the crime rate of the defendant’s residence, as this brings light to the rates of violence and crime in the given town or suburb. Heavier policing and patrol in minority saturated suburbia can often increase violence and arrest statistics for individuals residing in those areas, in comparison to districts that are populated with white Americans (Zhang & Han, 2021, p.1219). Accordingly, as COMPAS is a statistics based algorithm, this makes black defendants vulnerable to high-risk scores. This can be reflected in the graph below, which demonstrates COMPAS’s violent risk score among 1,912 black defendants, and 1,459 white defendants (Larson et al., 2016).

A mere glimpse at the graphs indicates that there is a clear disparity between the distributions of COMPAS risk scores of white and black defendants (Larson et al., 2016). While it is unclear if this specific data set takes into account socioeconomic factors, it is clear that these automated systems operate and govern in favour of the white majority (Noble, 2018).

Final Thoughts

When wielded correctly, algorithms promote optimisation and efficiency in our day to day lives. Yet, as examined through this analysis, the growing ubiquity of algorithms in our networked sphere certainly raises questions concerning the training of data, transparency of algorithms, and the social and cultural impacts of algorithmic automation (Olhede & Wolfe, 2018; Andrejevic, 2019). In the case of COMPAS, the algorithmic outputs of risk assessments are a reflection of the historical biases and discrimination embedded into the training data. Until data scientists undergo training and quality assurance, and firms become transparent about their automated decisions, algorithmic bias is unfortunately here to stay.

References

Andrejevic, M. (2019). Automated Culture. In Automated Media. London: Routledge, pp. 44-72.

Bains, J. (2021). Bias in Search Engines And Algorithms: Home. Retrieved April 6, 2022, from https://libguides.scu.edu/biasinsearchengines

Campbell, A.F. (2019). Job ads on Facebook discriminated against women and older workers, EEOC says. Retrieved April 6, 2022, from https://www.vox.com/identities/2019/9/25/20883446/facebook-job-ads-discrimination

Chander, A. (2017). The Racist Algorithm? Michigan Law Review, 115(6), 1023–45.

Danks, D., & London, A.J. (2017). Algorithmic Bias in Autonomous Systems, Proceedings of the 26th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Melbourne, Australia: https://www.andrew.cmu.edu/user/ddanks/papers/IJCAI17-AlgorithmicBias-Distrib.pdf

Fazelpour, S., & Danks, D. (2021). Algorithmic bias: Senses, sources, solutions, Philosophy Compass, 16(8), 1-16.

Gwaga, A., & Koene, A. (2018). Minimising Algorithmic Bias and Discrimination in the Digital Economy. Retrieved April 3, 2022, from https://aanoip.org/minimizing-algorithmic-bias-and-discrimination-in-the-digital-economy/

Just, N., & Latzer, M. (2019). Governance by algorithms: reality construction by algorithmic selection on the Internet, Media, Culture & Society ,39(2), 238-258.

Kossow, N., Windwehr, S., & Jenkins, M. (2021). Algorithmic transparency and accountability. Retrieved from Transparency International website: https://knowledgehub.transparency.org/assets/uploads/kproducts/Algorithmic-Transparency_2021.pdf

Larson, J., Mattu S., Kirchner L., & Angwin, J. (2016). How We Analyzed the COMPAS Recidivism Algorithm. Retrieved April 6, 2022, from https://www.propublica.org/article/how-we-analyzed-the-compas-recidivism-algorithm

Lee, N.T., Resnick, P., & Barton, G. (2019). Algorithmic bias detection and mitigation: Best practices and policies to reduce consumer harms. Retrieved April 5, 2022, from https://www.brookings.edu/research/algorithmic-bias-detection-and-mitigation-best-practices-and-policies-to-reduce-consumer-harms/#footnote-6

Logically (2019). 5 Examples of Biased Artificial Intelligence. Retrieved April 3, 2022, from https://www.logically.ai/articles/5-examples-of-biased-ai

Musiani, F. (2013). Governance by algorithms, Internet Policy Review, 2(3), 1-8.

Noble, S.U. (2018) A society, searching. In Algorithms of Oppression: How search engines reinforce racism. New York: New York University. pp. 15-63.

Park, A.L. (2019). Injustice Ex Machina: Predictive Algorithms in Criminal Sentencing. Retrieved April 6, 2022, from https://www.uclalawreview.org/injustice-ex-machina-predictive-algorithms-in-criminal-sentencing/#_ftn5

Serwin, K., & Perkins., A.H. (2018). Algorithmic Bias: A New Legal Frontier. Retrieved April 5, 2022, from https://www.iadclaw.org/assets/1/7/18.1_-_REVIEWED-_Serwin-_Algorithmic_Bias.pdf

Weiss, H. (2019). Artificial intelligence is too white and too male, says a new study. Retrieved April 6, 2022, from https://www.dazeddigital.com/science-tech/article/44059/1/artificial-intelligence-is-too-white-and-too-male-says-a-new-study

Zhang, J., & Han, Y. (2021). Algorithms Have Built Racial Bias in Legal System-Accept or Not?, Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Social Development and Media Communication, Sanya, China: https://www.atlantis-press.com/proceedings/sdmc-21/125968551