Have you ever thought about the origin of your own opinions when you express them on a specific issue? Possibly came from someone’s social media post that you strongly agree with. However, what if your opinions are biased, and whatever you view might have been personalised specifically for you?

Figure.1 Viewing news on the media platform. Retrieved from:https://www.bbc.com/ukchina/simp/vert-fut-44996579

Nowadays, social networks provide a global platform where anyone can easily find the exact information they are looking for. Especially during the pandemic, various social restrictions forced more and more people to search for news via digital media in their daily lives. Take Facebook as an example. Facebook is the most dominant network for people finding, reading, and watching the news. A large percentage of respondents in the Digital News Report (2016) said they get news or ideas from Facebook. On the side of the platform, there are 1.15 billion users and 699 million daily active users on Facebook, and more than 3.5 billion contents are shared every week (Nagulendra & Vassileva, 2014). The large volume of data can easily result in platform overload.

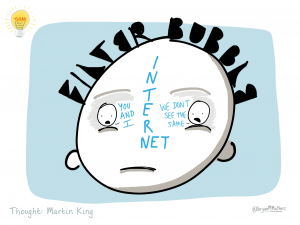

Figure. 2 Viewing Facebook news in eyes Retrieved from: https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_9655584

But how did Facebook handle this issue? It utilises the filtering function to reduce the amount of irrelevant content while presenting the most relevant content to users. Although this kind of personalised filtering system could create a comfortable space that allows users only to view posts similar to their position. The purpose has shifted from delivering new events to only recommending content that matches users’ preferences, causing them to accept similar information passively, creating a “filter bubble”. Individualised recommendation systems make it convenient for users to adopt information. Still, at the same time, it also creates the “filter bubble” effect, which causes the loss of opinion autonomy (Bozdag & Van Den Hoven, 2015).

In this blog, I will discuss the concept of the filter bubble, and how it works in the blinding victory of U.S. former president Donald, Trump winning the electoral. In addition, I will critically arise the thinking about whether the filter bubble becomes a threat to a democratic society. And at the last, I will propose a future prospect on filter bubble.

– The understanding of the Filter bubble

Paraiser (2011) introduced the concept of filter bubbles, which is an algorithmic filtering technique to limit access to more diverse perspectives on a particular subject. In other words, filter bubbles occur as a result of social media algorithms that introduce like-minded people to interact with each other, creating an environment where users are exposed to congenial, opinion-confirming content to the exclusion of more diverse, opinion-challenging content (Kitchens, et al., 2020). It could draw people to identify the viewpoint rather than challenging or critical thinking about the particular views. Filter bubbles could create a state of cognitive isolation as a result.

Causes for Filter Bubble

However, what circumstances will arise a filter bubble? The obvious cause is the algorithm’s over-recommendation. The disparity between classes and geographies on social networks determines users’ features. And new media platforms’ precise clustering of users and personalised recommendations contribute to this trend, resulting in a disparity between the different groups of users receiving tweets. The over-recommendations caused by algorithms tend to homogenise and polarise access to information for the same groups of people and reinforce the individual’s filter bubble. Kreitner(2016) proposes that fake news is spread by users sharing unverified information from unknown sources. But the personalised recommendations will prevent users from viewing information that contradicts their own beliefs. Therefore, it exacerbates group bias after audiences watch this unreal news. As a result, users’ information adoption process is widely influenced by algorithms and unconsciously limited to “filter bubbles” that match their information preferences.

Secondly, the causes of filter bubbles are closely associated with users’ habits and psychological situations. Matias et al.(2017) argue that even if users don’t get trapped in the online bubbles, they still cannot escape the biases and limitations of their opinions in the real world due largely to the herd mentality. Facebook’s core data science team analysed the interaction trajectories of 10.1 million U.S. Facebook users and found that the type of information they receive is affected by factors like how diverse their friends are(Karyotis et.al, 2018) The “filter bubble” isn’t all caused by algorithmic recommendations, but rather by users’ self-selection. Indeed, the personalised recommendations rely on the user’s behavioural history, but the user’s active action is also one of the decisive factors that ultimately lead to filter bubbles.

– Trump’s mature manipulation of the filter bubble

The former U.S. President Donald Trump is a billionaire businessman who has never held elected office. In 2016, Trump defeated Hillary Clinton to win the electoral, the one who is more recognised by the public. During his tenure, he has been called nuts or the most irresponsible president, but still has numerous loyal supporters who love him steadfastly. Most people cannot understand why Trumpism has flourished, and so many other people are insulated from it. How come a person who is so controversial has so many faithful followers? Or do Trump’s followers make decisions with their independent minds and autonomous judgment?

Figure.3 Trump’s loyal supporters Retrieved from: https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/should-democrats-try-to-win-over-trumps-supporters-or-just-move-on/

To answer this question, let’s look at the 2016 United States electoral outcome. From the side of the voter, indecisive and curious voters often use search engines and social media platforms to research candidates while making the final choice, and filter bubbles may work a significant effect at this moment. Assume that voters are given biased search results, which means the final result becomes unfair to some extent.

From the side of social media platforms, Facebook and Google’s algorithmic personalisation tools may insulate people from opposing viewpoints, causing people holding diverse views to be placed in an opposite social environment. According to research, Facebook has reached 67% of American adults, and most of them, around 40% of adults, said that they get news from Facebook (Baer, 2016). We can conclude that this platform has unprecedentedly worked to centralise public online opinions. It also stands as a significant part of America’s political judgment. The massive and oriented information on Facebook makes people easier to make political decisions. That also means the mass users’ opinions and thoughts are largely dependent on the composition of our social networks. According to this phenomenon, Facebook data scientists took over six months to research the action of Facebook users. Research finds some users who like to watch “soft” content like entertainment or celebrity information are less likely to click hard content in their feeds. They only clicked 7% of political issues or sciences in their whole feeds (Baer, 2016). That means Facebook’s algorithm gradually causes users less likely to accept cross-disciplinary content. They trust their viewing content, and treated the “news feed” as “a feed of my friends’ opinions.”

Accordingly, it can be shown that the majority of Trump voters fell into the filter bubble phenomenon on social media. Personalised search algorithms only show voters what they want to see rather than what is actual (Palano,2019). They will get grouped by the primary interests or demographic groups on the platform algorithm setting. The majority of these groups are made up mostly of the working class, looking for hope from Trump if he wins the election (Smith, 2016). The lower-income white supporter is not what we usually call middle class: It’s more accurately referred to as a working class. Lipset wrote in 1959 that “authoritarian attitudes and ethnic prejudices are more natural in lower classes than in middle and upper classes” (Smith, 2016), whereas Donald Trump’s words represented that he is the most staunch defender of white working-class politics, he makes this group of people feel safe. Meanwhile, Trump and his team are making sure that there are enough discussion contents and searches relevant to this category, that straightly heading to his target voters, and therefore consolidating his support. Trump’s supporters would never know that they are already disconnected from other viewpoints and trapped in a cycle of filtered messages.

As the result, Trump’s supporters are therefore likely to create small political parties with similar views, to prevent themselves from receiving any information challenging their beliefs. Users might receive different search results and friend list updates when using the same keyword, according to Pariser (2011). The reason for this is that the system can prioritise, filter, and hide information based on the user’s previous interactions with the system and other factors (Bozdag 2013; Diakopoulos 2014). Especially when it comes to political information, such as deciding about voting for which candidate, a filter bubble that happens in search results may cause the voter to overlook opposing viewpoints on a topic. That means, that Trumpists might receive biased information, and this information is all suits their thoughts. Nevertheless, this kind of negative effect of the filter bubble will be the erosion of the civic discourse, reducing the information quality and the diversity of perspectives.

– Filter Bubbles and Democracy

As a very rough description, democracy refers to a collective decision-making process that is characterised by equality among the participants (Christiano 2006). There are various models of democracy but in this blog. I will mainly talk about the deliberative democracy model that emphasised to make decisions from individual preferences and autonomy. Because in relevant to Trump’s cases, his wining is largely up to the individual’s preferences’ vote. According to the previous section, the filter bubble intentionally affects the voters’ thoughts and decisions. Under the liberal view of democracy, it states to uphold the values of freedom of choice, reason, and individuals should violate their autonomy, as it will interfere with their ability to choose freely, and to be the judge of their interests. But the emergence of the filter bubble becomes an obstacle to the realization of deliberative democracy.

Filter bubbles are a hazard to achieving deliberative democracy, it limits and controls the liberty of thought. This is due to filtering bubbles leading to homogenising information and giving audiences one-sided views, which result in recipients receiving messages that are more biased and less objective. When this occurs, the diversity of available information and ideas is reduced, making it more difficult for people to discover new perspectives, ideas, or facts. A continuous filter bubble without recognising differences will lead to the result of an information cocoon, which will lessen the chances of achieving democratisation. The term information cocoon refers to a phenomenon in which people are accustomed to pursuing their self-interests within their preferred information domain, essentially binding their lives to it (Peng & Liu, 2021).

As technology provides an independent and boundless space of knowledge and thought, some people may further escape the contradictions of society and isolate their thoughts from others’ opinions. The cocoon of data grips readers, allowing them to share and publish the same information. This will make it impossible for people to consider things objectively and see the bigger picture. Consequently, individuals who are democratic will not have perfect, liberty arguments, which leads to lessening the completely fair election results.

– Future Directions of Filter Bubble

The emergence of a filter bubble indicates that the web does not interfere with values. Although it has neither good nor evil, it is not neutral. As Stiegler (2001) points out, there are technical trends and technical facts. A technological trend is something that does not change by an individual’s ability in the future, it will develop in a certain direction like an unstoppable trend. But on the other hand, technological facts are inevitable but is possible to make some changes. The filter bubble phenomenon is a technological fact. In the future, when everyone realised the problem of the filter bubble, people could ask Internet companies to make any arrangements. For example, providing better quality content and expressing a more comprehensive ethical state. Those technological companies can also make adjustments to some algorithms, indicators, and elements.

All opinions should be questioned. All situations should be critically reflected upon. Filter bubbles provide a diversity of perspectives, and also, in a way, have become a part of our social structure. It is important to challenge them. Whether we are conducting academic research or browsing the contexts, we should spontaneously show openness to diversity of opinions. As more people become aware of filter bubbles, it may become a catalyst that encourages people to seek alternative news sources and to accept opposing views with an open mind. At that time, true democratisation would follow.

Reference Lists

Baer, D. (2016). The ‘Filter Bubble’ Explains Why Trump Won and You Didn’t See It Coming. The Cut. Retrieved 9 April 2022, from https://www.thecut.com/2016/11/how-facebook-and-the-filter-bubble-pushed-trump-to-victory.html.

Bozdag, E., & Van Den Hoven, J. (2015). Breaking the filter bubble: democracy and design. Ethics and information technology,17(4), 249-265.

Karyotis, C., Doctor, F., Iqbal, R., James, A., & Chang, V. (2018). A fuzzy computational model of emotion for cloud-based sentiment analysis. Information Sciences, 433, 448-463.

Kreitner, R. (2016). Post-Truth and Its Consequences: What a 25-Year-Old Essay Tells Us About the Current Moment. The Nation. Retrieved 9 April 2022, from https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/post-truth-and-its-consequences-what-a-25-year-old-essay-tells-us-about-the-current-moment/.

Newman, N., & Fletcher, R. (2016). REUTERS INSTITUTE DIGITAL NEWS REPORT 2016 [Ebook] (1st ed., pp. 7-10). The University of Oxford. Retrieved 10 April 2022, from https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/research/files/Digital%2520News%2520Report%25202016.pdf.

Matias, J. N., Szalavitz, S., & Zuckerman, E. (2017). FollowBias: supporting behaviour change toward gender equality by networked gatekeepers on social media. In Proceedings of the 2017 ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing, 1082-1095.https://doi.org/10.1145/2998181.2998287

Moeller, J., & Helberger, N. (2018). Beyond the filter bubble: Concepts, myths, evidence and issues for future debates.

Palano, D. (2019). The truth in a bubble is the end of ‘audience democracy and the rise of ‘bubble democracy’. Soft Power, 6(2), 36-53. DOI: 10.14718/SOFTPOWER.2019.6.2.3

Pariser, E. (2011). The filter bubble: How the new personalized web is changing what we read and how we think. Penguin.

Peng, H., & Liu, C. (2021). Breaking the Information Cocoon: When Do People Actively Seek Conflicting Information?.Proceedings of the Association for Information Science and Technology,58(1), 801-803. https://doi.org/10.1002/pra2.567

Stiegler, B. (2001). Derrida and technology: fidelity at the limits of. Jacques Derrida and the Humanities: a Critical Reader, 238.