Online Harassment: The Current Situation And Dilemma Facing Online Harassment

Graphic 1. Screenshot from YouTube. #MoreThanMean. 2016.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9tU-D-m2JY8

Introduction:

Bullying and harassment are increasingly moving online in today’s technologically advanced environment (“Online harassment”, 2020). Users are obliged to accept confused sources of information, untrustworthy websites, and online harassment while humans enjoy the carnival party brought about by the Internet. One aspect of Internet governance that demands special attention is online harassment. In the United States, four out of ten people have been or are being harassed online, five out of ten people have been harassed online because of their sexual orientation, and eight out of ten people have been harassed online in gaming communities. Each line of data represents a real individual who is being unfairly cyberbullied, hence the focus of attention and solutions to this problem is on researching and analyzing online harassment. This blog will examine cyber harassment data, use case studies to demonstrate the negative impact of cyber harassment on individuals’ real lives and society as a whole, and finally discuss the options and measures available to combat cyber harassment at the level of internet platforms and individuals.

Overview:

1.What is online harassment?

To protect yourself and others on the Internet, the first task is to recognize what online harassment is.

Humphris (2019) defines online harassment as ‘the use of information and communication technologies by an individual or group to repeatedly cause harm to another person with relatively less power to defend themselves’. In other words, it is about harmful behavior directed at an individual or group, including cyberstalking, sexting, trickery, upskirting, etc. Some researchers consider online harassment to be a new type of traditional (offline) bullying, with the exception that it occurs online and the substance of the bullying remains the same (Barkoukis, Brighi, Casas et al, 2015). However, “Online harassment” (2020) argued that compared to face-to-face bullying, cyberbullying, as a kind of chronic stress, has more long-term psychological and physical effects.

2.Who is being harassed on the internet?

We are all potential victims of online harassment.

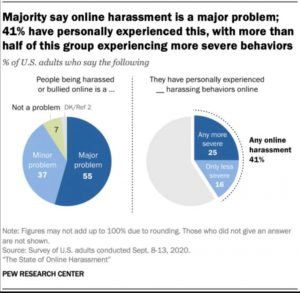

As stated by the latest Pew chart, 41% of individuals have experienced online harassment, with more than half of those have experienced more serious behaviors (graphic 2). Although this figure has not changed since 2017, both the breadth (variety) and depth (intensity, severity) of online harassment have increased (Pew Research Center, 2021). While this graphic indicates the staggering coverage of online harassment, when combined with the types of individuals targeted, it reveals that the social impact of online harassment is more serious than we might imagine. In terms of Pew Research Center (2021), more than 80% of the Internet gaming community has been subjected to online harassment, while 50% of lesbians, gays, and bisexuals have experienced online harassment because of their sexual orientation. What’s more, 54% of black people and 47% of Hispanics have experienced online harassment as a result of their race.

In conclusion, the two Pew Research Center studies show the current state of online harassment and its social impact in terms of population coverage and group categories. These disheartening statistics make it clear that each and every one of us is a potential victim of online harassment. Fortunately, these data now helps us to begin consciously avoiding online harassment; however, comprehensiveness of the data must to be considered. Due to the recent advent of the COVID19, many people are now studying and working online, resulting in the emergence of a new group that was not present in previous survey data. They may have encountered more online harassment as a result of restrictions and shifts from physical to online for schools and workplaces (Anderson, 2022). Therefore, to improve the accuracy of the data, assessment agencies should consider the new Internet student population.

Graphic 2. Source: Pew Research Center. 2021. Edition. Retrieved from:

Case study:

Authoritarian data provides us with an idea of the scope and frequency of online harassment, but how severe is the harm caused by harassment? What impact does it have on the individual and society levels? Following these questions, I would use a combination of case studies and theoretical knowledge to highlight society’s attempts to combat online harassment.

#MoreThanMean Campaign: An anti-online harassment campaign for vulnerable groups

As a digital media campaign, the #MoreThanMean campaign was pioneered by Just Not Sports, an independent media organization. The campaign’s goal was to make society aware of the limitations and hardships faced by women working in sports journalism through online harassment, in order to increase social inclusion of women in sports journalism, break through the stereotypical male-dominated sports journalism industry, and hopefully give women the courage to enter the sports journalism workplace, and other male-dominated industries. The campaign was launched in April 2016 and quickly gained over 3 million views, attracting the attention of mainstream media and progressive platforms at the time, and has since reached over 4.8 million views.

Graphic 3. Screenshot from YouTube. #MoreThanMean. 2016.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9tU-D-m2JY8

This seemingly feminist movement, however, does not position itself as ‘feminist,’ but rather focuses on how feminist ideas can gain traction in cyberspace (Antunovic, 2018), attempting to reverse women’s passive position online in order to protect women’s rights. The #MoreThanMean video features two female sports talk show hosts, and the show invites male readers to participate at random and asks them to read real Twitter posts. The tweets aren’t quite as extreme at the begin of the reading, the readers interacted with the journalists, and the atmosphere was relatively relaxed until later on, when they began reading some extremely abusive words, the male readers lowered their heads and stopped looking at each other with the female journalists.

Graphic 4. Screenshot from YouTube. #MoreThanMean. 2016.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9tU-D-m2JY8

Not only the male readers themselves, but also the viewer in front of the screen, was flabbergasted by this outpouring of emotions. The unrestricted nature of online harassment, the apparent openness to free speech, and the usage of even invisible anonymity (Chen et al., 2018) effectively expresses the dehumanizing and demeaning expressiveness of harassing posts on Twitter. Social media platforms are also places for unfiltered abuse (Antunovic, 2018), and this type of online harassment, which focuses on abusing women on public platforms, was first shown in public, but not for the first time in front of these female journalists. Julie DiCaro (2015), a rape victim, faces online harassment on Twitter on a frequent basis, with comments such as “Get raped again!” and even death threats. There is no doubt that the campaign was a success, bringing unprecedented attention to female journalists, but there is another aspect to it that is worth considering.

The #MoreThanMean campaign’s popularity stems from the fact that it emphasizes how this type of online harassment is linked to the nature of work, the workplace, and gender, as well as providing a focal point for the battle against female online harassment in the digital media sphere. It also demonstrates how other groups affected by online harassment, such as bullied schoolchildren, might be empowered. However, there were certain evident issues throughout the campaign. This male-dominated campaign of organization, reading, and reflection did not appear to make a significant difference in the position of female journalists who are verbally assaulted, marginalized, criticized, and even threatened. It is apparent that the campaign remains inside the traditional paradigm, that it has not shifted away from a male-dominated perspective. Second, re-exposure of journalists to widespread public acceptance of online harassment and harassment in journalism can easily lead to them being labeled as emotionally sensitive or professionally toxic, potentially preventing them from reporting harassment or seeking help, and resulting them down a more marginalized path (Chen et al. 2020; Kotisova 2017, 2019).

Evaluation:

What’s the solution for online harassment?

It is difficult to find a straightforward answer to online harassment (York, 2015). Online harassment has had varied degrees of harmful impact on individuals and society, even harming people’s daily lives, according to the facts from the aforementioned publications and the social phenomena. In response to the academic and societal debate around Twitter, the company has made improvements for this reason as well. Twitter enlisted the Women, Action, and Media (WAM!) network to assist with online abuse monitoring and remediation (York, 2015). harassment, the individual behind the account could re-register a new account for free and resume their own anonymous harassment, which was enabled by the platform’s nature. So, to offer a different solution, is it possible to solve this problem using external technologies without altering the platform’s purpose? Today, there are several solutions to help with management, such as BlockTogether (York, 2015), dashboards that enable users manage and restrict other nuisance accounts, and are often regarded as being just the right amount of helpful by most users. However, such management solutions have limitations, and it is possible that shared accounts would be blocked.

There are measures that can be taken to reduce the risk of online harassment, but they cannot offer perfect protection (Anderson, 2022). First and foremost, mindful protection and discernment of messages is an efficient strategy to prevent online abuse on a personal level. Cultivate and cultivate vigilance when using the Internet, and attempt to prevent disagreeable online behavior. Second, safeguard digital privacy, including email addresses, account numbers, and passwords, and familiarize yourself with and understand the platform’s policies before using it. Third, use your browser’s privacy settings to communicate freely without disturbing others. Fourth, persons who are subjected to cyberbullying or online harassment can report it to defend their privacy and safety. Furthermore, it is vital to keep an eye on the situation. Furthermore, in order to effectively promote the governance of the general Internet environment, it is required to monitor the platform’s governance of online harassment and actively exercise the right to monitor the platform.

Conclusion:

Focusing on Online Harassment, one of the most difficult issues in Internet Governance. This blog has analyzed the latest data from the Pew Research Center on online harassment, analyzing the depth and breadth of its impact on society. The #MoreThanMean campaign also represents a group of female journalists who are victims of online harassment standing up to it in real life. Despite its limitations, its influence has been a significant step forward in the battle against online abuse, encouraging more victims to speak up. Finally, this blog looks at how platforms can try to manage online harassment accounts and how users can safeguard their privacy via the lens of Internet platform governance and autonomy. To build a benign Internet environment and achieve greater Internet governance, many efforts from platforms and governments, institutions, and deliberate information control by users are still required. However, due to the current constraints of Internet governance, societal concerns like online harassment will continue to necessitate the collaboration of numerous stakeholders to resolve the current impasse. The Internet ecosystem would be in turmoil if adequate measures and ways of governance are not supplied in a timely manner, given the ever-increasing figures of victims of online abuse.

Reference:

Anderson, K. (2022). Getting acquainted with social networks and apps: understanding, preparing for and responding to online harassment. Library Hi Tech News, 39(2), 6-10. doi: 10.1108/lhtn-06-2021-0042

Antunovic, D. (2018). “We wouldn’t say it to their faces”: online harassment, women sports journalists, and feminism. Feminist Media Studies, 19(3), 428-442. doi: 10.1080/14680777.2018.1446454

Chen, G., Pain, P., Chen, V., Mekelburg, M., Springer, N., & Troger, F. (2018). ‘You really have to have a thick skin’: A cross-cultural perspective on how online harassment influences female journalists. Journalism, 21(7), 877-895. doi: 10.1177/1464884918768500

Dewey, C. (2014). #YesAllMen: Online harassment isn’t just a women’s issue — it hurts guys, too: A new report explains the critical differences between the male and female experience online. Washington: WP Company LLC d/b/a The Washington Post. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.library.usyd.edu.au/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/blogs-podcasts-websites/yesallmen-online-harassment-isnt-just-womens/docview/1615771984/se-2?accountid=14757

Humphris, D. (2019). Tackling Online Harassment And Promoting Online Welfare (p. 14).

Majority say online harassment is a major problem; 41% have personally experienced this, with more than half of this group experiencing more severe behaviors. (2022). Retrieved 8 April 2022, from https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2021/01/13/the-state-of-online-harassment/pi_2021-01-13_online-harrasment_0-02/

Online harassment: The relationship between cyberbullying and job dissatisfaction in the workplace. (2021). Human Resource Management International Digest, 29(2), 29–31. https://doi.org/10.1108/HRMID-11-2020-0251

Roughly two-thirds of adults under 30 have been harassed online. (2022). Retrieved 7 April 2022, from https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2021/01/13/the-state-of-online-harassment/pi_2021-01-13_online-harrasment_0-03/

York, J. (2015). FCJMESH-008 Solutions for Online Harassment Don’t Come Easily. The Fibreculture Journal, (26), 297-301. doi: 10.15307/fcj.mesh.008.2015

Jhaver, S., Ghoshal, S., Bruckman, A., & Gilbert, E. (2018). Online Harassment and Content Moderation. ACM Transactions On Computer-Human Interaction, 25(2), 1-33. doi: 10.1145/3185593