Introduction

Due to the rapid development of the Internet today, its functions are increasingly rich, making it like a miniature landscape of society. Many social phenomena and behaviors are also reproduced on the Internet. And that includes hate speech. (Matamoros-Fernández, 2017) Online hate speech has become more common with the globalization of the Internet. Research shows that in 2017, 41 percent of Internet users in the United States reported experiencing some degree of online hate speech and harassment (Flew, 2021). Through the amplification of digital platforms and social media, the harm and threat of online hate speech cannot be ignored.

Firstly, I will research about the state of online hate speech to illustrate its threat in this blog. Secondly, I will analyze the challenges and dilemmas of online hate speech governance from the perspectives of Internet users, internet governance and legal framework. Thirdly, as a research method, I will use case study to make a more intuitive evaluation and further emphasize the harm of online hate speech. By analyzing the imperfections of the current governance of online hate speech to find the direction of future exploration.

About Online Hate Speech

How to define hate speech?

From the perspective of discourse, hate speech is considered as “public speech that defame or is hostile to a certain person or group based on gender, race, nationality, religious belief or other group characteristics, or praises and encourages violence against the target in words”. (Matamoros-Fernández, 2017) These derogations and insults can be explicit or implicit, including sexism, regionalism or racism, depending on the characteristics of the group.

From the legal perspective, the definition of hate speech varies from region to region or country to country. In some regions or countries, the primary legal basis for identifying hate speech is the identity and characteristics of the group being abused. In other countries, some hate speech is vaguely defined and constitutionally protected. (Herz and Molnár, 2012) What victims can do is to seek legal help and remedies for themselves, depending on the specific circumstances of the violence or the encounter, depending on the corresponding provisions of civil and criminal law.

Particularity of online hate speech

There is a significant difference between online hate speech published on digital platforms and hate speech in the real world, both in the process of generation and the severity of the consequences. That is why Internet platforms and digital media are supposed to be amplifiers of hate speech (Herz and Molnár, 2012).

On the one hand, as revealed above, some countries lack legal restrictions on the online hate speech, which makes the perpetrators unscrupulous. The victim’s recourse to other laws often results in the perpetrator receiving only a lesser sentence (Herz and Molnár, 2012). Such a paltry price does not serve as a wake-up call to the perpetrator.

On the other hand, what makes the Internet an amplifier for hate speech has to do with the Internet algorithms that aggregate similar messages. Hate speech is aggregated, and victims are further horrified by the sheer volume and consistency of hate speech victims receive from digital platforms. (Gorwa et al., 2020) In addition, with the development of Internet technology, it provides more possibilities for netizens to connect with each other, which allows online hate speech to infiltrate into more channels. At the same time, the globalization of the Internet allows more people to participate in online media, and more and more diverse group identities coexist in the same platform community. Taken together, these causes contribute to the exponential spread of hate speech.

Although there is a view that speech does not directly lead to public violence (Flew, 2021), the possibility that people can be aroused by mass effect in the context of inflammatory speech for a long time cannot be ignored. Because the overwhelming online hate speech affects not only the victims or the victim groups, but also the perpetrators who participate in the online hate speech are inevitably affected by a subtle influence. Since one of the hallmarks of hate speech is that the perpetrator rationalizes his or her hostility to the victim by attributing generally repugnant qualities to someone’s group identity (Flew, 2021). The subconscious denial of the victim’s dignity results in the perpetrator becoming more aggressive. And this kind of consequence as a kind of social hidden trouble cannot be ignored.

As it turns out, the level of violence that accompanies hate speech online is also escalating. Most of the victims received responses to offensive online comments and channel messages, sexual harassment and life-threatening content. Some of the victims of online hate speech will be affected even in real life, as their personal information is almost completely disclosed under “doxing” (Flew, 2021). Victims’ other digital platform accounts, real names, contact numbers, home addresses and even personal histories were doxed. A small number of victims may even be followed, followed or photographed. The barrage has forced some victims to cancel all media channels and even leave their hometowns. The more traumatized victims are unable to return to group life because they have difficulty maintaining trust in society (Brown, 2022).

Dilemmas and Challenges

Although the possible consequences of online hate speech are serious, there is still no perfect and effective method to prevent online hate speech. This is due to resistance from users, platform regulation and the law.

Figure 1: Hate speech under the cover of freedom of speech

Complex resistance from huge number of users

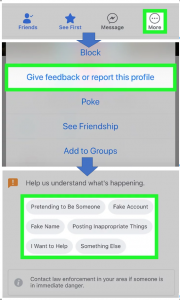

While users crave free speech, the boundaries of hate speech are blurred. Then there is a part of the perpetrator that does not see their words as hate speech or violence. On the other hand, hate speech is difficult to be censored and punished, because many perpetrators will use humorous rhetoric to cover up the aggression of the speech itself (Matamoros-Fernández, 2017).

As victims of online hate speech, most of them seek help from the platform and hope to be properly dealt with by the platform, but the results are often unsatisfactory. This should start from the digital platform’s complex reporting mechanism. The vast majority of digital platforms only passively receive and review reports from users (Bowers and Zittrain, 2020). And the procedure for users to report posts manually is complicated. Take Facebook as an example, users are required to provide screenshots, copy links of comments or posts, provide the account name of the person being reported, and so on. As shown in the figure (Figure 2), the report button is unobtrusive on the page and the operation is tedious. As more hate speech posts appear, it becomes more difficult to report them. And even if relevant evidence is presented, the complaint is likely to be dismissed.

Figure 2: The process of reporting users on Face Book platform

Dilemmas of platform governance

To be clear, under Communications Decency Act 230, Internet platforms and digital media developers are not responsible for content users post on their platforms. This sets the stage for Internet platform developers to remain neutral. (Byrd and Strandburg, 2019) But it also gives Internet users more freedom to create any content, including online hate speech. In order to maintain the image and business model of platform, some digital platforms do not directly intervene in the communication process of online hate speech. The inaction of platform is seen as favoring perpetrators of online hate speech (Matamoros-Fernández, 2017). The truth is that platform governance has moved towards paying attention to what users’ post, but its effectiveness remains questionable. In addition to the above-mentioned reasons (hate speech is difficult to screen), the limitations of current Internet technology and digital algorithms are also one of reasons. As platform censors some sensitive words from being posted, users can often find other words to replace them, or create a new metaphor.

Challenges to the existing legal framework

Under the existing legal framework, laws against hate speech include those aimed at maintaining public order and those aimed at protecting human dignity. The problem is that laws designed to protect public order require higher thresholds to be breached and are therefore not usually enforced. Laws designed to protect human dignity fall short on punishment. Laws designed to protect human dignity allow trials for online hate speech to be carried out, but punishments are often mild. (Bell, 2009)

Evaluation: Take the case of Maria Ressa

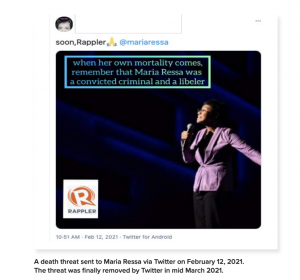

I will use the experience of Filipino journalist Maria Ressa, CEO of Rappler, as an example to further assess the threat of online hate speech by putting the discussion in a real context. Maria Ressa, an investigative journalist and media executive in the Philippines, has won the Guillermo Cano Prize for Press Freedom. The award recognizes advocates of media freedom, especially those who are at risk for doing so. Indeed, Maria Ressa risks her personal safety every day. There is evidence that Maria Ressa is a frequent target of online hate speech. (Posetti et al., 2021) In 2016, she received 90 real-name or anonymous hate speech messages online every hour. The online hate speech included repeated slurs and threats to “rape Maria Ressa to death,” as well as viral memes that superimposed her head on male genitalia. Maria Ressa’s personal information was also doxed, including the address of her Manila newsroom.

Figure 3: Online hate speech against Maria Ressa

In addition to death threats and rape threats, perpetrators of online hate speech have been hostile to other features of Maria Ressa. The perpetrators slandered Maria Ressa because she is a woman, denied her dignity because of her skin color, and affronted her sexual orientation. (Posetti et al., 2021) Among other things, we can note that the online hate speech even targeted her career.

Using natural language processing, an analysis of abuse, threats and harassment collected from hundreds of thousands of Twitter and Facebook posts targeting Maria Ressa between 2016 and 2021 revealed:

- According to statistics, for every comment in support of Maria Ressa on her Facebook page, there were approximately 14 comments containing hate speech or personal attacks on Maria Ressa. And 34 percent of the 14 percent of hate speech categories could be classified as misogynistic, sexist and discriminatory.

- Nearly 60 percent of the hostile comments about Maria Ressa extracted from Facebook and Twitter sought to destroy her professional credibility as a journalist and the public’s trust in her by undermining her reputation. (For example, # Fake-News Queens; # “LIAR”; “# Presstitute”)

- Facebook and Twitter have both made promises to properly address hate speech comments about Maria Ressa. In fact, Facebook failed to effectively curb the hate speech perpetrated against Maria Ressa. According to Maria Ressa herself, she feels “much safer” on Twitter.

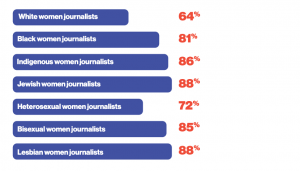

Figure 4: Different levels of online hate speech experienced by female journalists (Posetti et al., 2021)

In fact, Maria Ressa is not the only female journalist who has been victimized by online hate speech.

Analyzing 2.5 million social media posts, surveying 900 journalists in 125 countries and conducting more than 170 interviews, UNESCO’s new report shows how women journalists are victimized by online hate speech. One in five of those surveyed had been attacked offline as a result of online hate speech, while more than a quarter had been left with serious psychological trauma. More than 40 percent of female journalists surveyed said they had been targeted by orchestrated by perpetrators. (Posetti et al., 2021)

Figure 5: Online hate speech is depriving female journalists of their media freedom

Source:https://en.unesco.org/sites/default/files/the-chilling.pdf

What is orchestrated online hate?

In the case of Maria Ressa, online hate speech against Maria Ressa created an enabling environment for real-life persecution of Maria Ressa. In less than two years, ten arrest warrants were issued and Maria Ressa was detained twice. Maria Ressa was fighting nine different cases at the time. And with the stigmatization of online hate speech, if she is convicted, she could spend the rest of her life in prison. The online hate speech that Maria Ressa encountered turned out to be part of an elaborate attack on the news media by perpetrators. (Posetti et al., 2021) These facts prove that the damage caused by online hate speech is not entirely virtual. Even worse, online hate speech is a prelude to the perpetrator’s destruction of a person or group of people.

Result and Prospect

Efforts to intervene against online hate speech remain fraught with difficulties, with a lack of clear criteria for determining what constitutes hate speech and resistance from users, media platforms and lawmakers. Efforts to intervene in online hate speech continue to be hampered by a lack of clear standards to determine what constitutes hate speech, resistance from users, media platforms and lawmakers, and the inability to reach a broad consensus. In spite of this dilemma, it is imperative to curb online hate speech, because the case of Maria Ressa proves that the harm caused by online hate speech is no longer completely virtual. The absolutism of free speech and digital media platforms are becoming important tools of anti-society (Flew, 2021). And how to balance freedom of speech to moderate censorship, and how to complement the law about online hate speech to make it more perfect, national conditions, these issues are the direction we need to explore at present and in the future.

References:

Bell, J. (2009). Restraining the heartless: Racist speech and minority rights. Ind. LJ, 84, 963.

Bowers, J., & Zittrain, J. (2020). Answering impossible questions: Content governance in an age of disinformation. Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) Misinformation Review. https://doi.org/10.37016/mr-2020-005

Brown, A. (2022). Models of governance of online hate speech. Retrieved 8 April 2022, from https://edoc.coe.int/en/fundamental-freedoms/10357-models-of-governance-of-online-hate-speech.html

Byrd, M., & Strandburg, K. J. (2019). CDA 230 for a Smart Internet. Fordham L. Rev., 88, 405.

Flew, T. (2021). Chapter 3: Hate Speech and Online Abuse. Regulating platforms. pp. 91-93. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Gorwa, R., Binns, R., & Katzenbach, C. (2020). Algorithmic content moderation: Technical and political challenges in the automation of platform governance. Big Data & Society, 7(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951719897945

Herz, M., & Molnár, P. (Eds.). (2012). The content and context of hate speech: Rethinking regulation and responses. Cambridge University Press.

Matamoros-Fernández, A. (2017). Platformed racism: The mediation and circulation of an Australian race-based controversy on Twitter, Facebook and YouTube. Information, Communication & Society, 20(6), 930-946.

Posetti, J., Shabbir, N., Maynard, D., Bontcheva, K., & Aboulez, N. (2021). The Chilling: global trends in online violence against women journalists. research discussion paper, UNESCO, https://unesdoc. unesco. org/ark:/48223/pf0000377223.