Introduction

As the use of the Internet has become mainstream since the beginning of the 21st century, people have become concerned about the risks of harm caused by online services, especially regarding the protection of children (Woods, 2021). Today, with the rapid development of the digital age, many online platforms, including social media, blogs, forums, and gaming sites, have rapidly surpassed traditional media, such as newspapers and radio, as the primary channels for people to obtain information, communicate, and interact with each other. However, against this background, a serious concern that cannot be neglected has slowly arisen, that is the potential harms that the content on online platforms may produce, such as defamation, discrimination, misleading information, hate speech and so on. The most effective way to deal with these risks is to establish online regulatory regimes and content moderation facilities to strictly monitor and filter content that should not be posted and discussed on the platform, in order to deal with potential online risks.

So, what is platform content moderation? What are the categories it is divided into and how is it specifically applied? Also, what are the consequences of a lack of effective content regulation? This blog is going to argue the importance of platform content moderation for maintaining a purified public platform and use Mumsnet, the UK’s most popular forum for parents, as an example to demonstrate what challenges a platform may face when it chooses to minimise its moderation policies and maximise the free speech space for its users.

Automated and Human Moderation

According to Roberts (2019), content moderation can be defined as the systematic screening of user-generated content published on websites, social media, and other online sources to assess whether the content is appropriate for a particular site, region, or jurisdiction. Different social media platforms have their own set of content moderation policies, currently there are two main forms of online content moderation, namely automated moderation and human moderation.

Automated moderation relies on artificial intelligence technology, which matches user-posted content with known and “unwanted” data to filter out what is allowed and what is unacceptable to post (Gerrard, Thornham, 2020). In terms of advantages, automated moderation can reduce the burden on human moderators by efficiently and substantially screening and blocking harmful speech. For example, Facebook has claimed that 65% of hate speech content is found and flagged by Facebook before users’ reports. In addition, Gillespie (2020) suggests that there is a certain partnership between automated and human moderation, as the algorithms can recognize the most shocking and scarring content on the platform, such as bloody violence, child abuse, etc., to protect human moderators from having to view them.

From the perspective of disadvantages, automated tools have limitations in content identification because the algorithms cannot perceive human speech context and may be biased in their understanding of the context, thus leading to incorrect judgments. For example, image recognition tools can identify nude body parts, such as breasts, in a video, but automated tools cannot identify whether this is an erotic message or breastfeeding, as algorithms can only locate the target but cannot interpret human culture (Vincent, 2019).

The job of human moderators is to manually review the user-generated content. While human moderation is more reliable than machine learning because of human empathy and contextual thinking, the downside of using human moderation is, first, the massive labor cost – for example, Facebook alone employs 15,000 content moderators working on its platform. The second is that it is psychologically exhausting for ethical considerations. A former Facebook content moderator said in an interview that they spend hours every day combing the dark side of the social network, flagging posts that violate its content policy and viewing brutal images such as those of Palestinian women who died in bombings. In 2020, Facebook mitigated a lawsuit by agreeing to pay $52 million to current and former moderators for mental health issues that arose in the course of their work (Newton, 2020).

Whether using automated or manual moderation, social media platform content moderation policies are critical to maintaining the order of a platform, and when a platform is missing appropriate moderation and regulation, a red flag is created.

Mumsnet’s Transphobia Issue

The intense debate over transgender issues on Mumsnet can be traced back to a 2015 documentary, “Transgender Children,” a BBC documentary by Louis Theroux that aired in April, in which Theroux documented some gender non-conforming children he met in San Francisco. In the wake of the documentary, Mumsnet has erupted into a hot topic of discussion about transgender kids. The site’s pages are filled with vicious comments about transgender people, with users asking whether such children should have access to male or female restrooms and bathrooms; some decrying the fact that no matter how many hormones are taken, males can never become females and females can never become males; and some pro-biological determinist users arguing that transgenderism is absolutely unacceptable (Morgan, 2021).

Going back to the initial purpose that Mumsnet was created for, Mumsnet is a London-based online forum founded in 2000 by Justine Roberts for parents of children and teenagers to discuss matters and support each other. As of today, Mumsnet is now the largest parent website in the UK, with around 7 million unique visitors and around 100 million page views per month (Mumsnet, 2022).

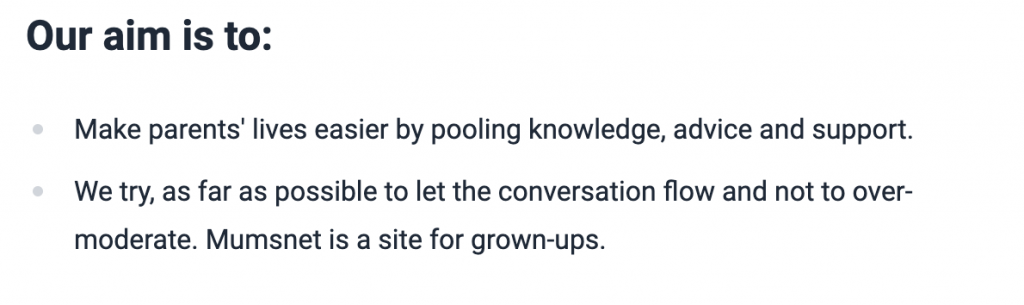

According to the guidelines on the website, Mumsnet is not a pre-moderated forum, nor is it an over-moderate forum. It supports freedom of expression, and its policy is to minimise interference and allow parents to have unhindered conversations. Based on its support for free speech, the website’s content moderation policy can be considered extremely lax, and it is this lax policy that has led to the rampant spread of extremist speech on the site. Mumsnet’s inaction on such speech has further provided anti-transgender groups with a safe haven, and even attracted activists from other social media platforms.

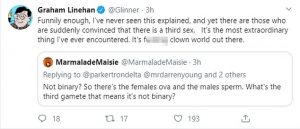

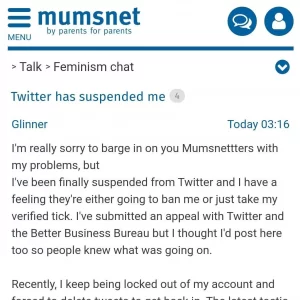

For example, Graham Linehan, an Irish television writer, was permanently suspended by Twitter for posting hate speech about transgender people on Twitter for repeatedly violating the platform’s rules against hateful behavior and platform manipulation. After having his account suspended by Twitter, Graham quickly posted a thread on Mumsnet complaining about his account being blocked by Twitter and attempting to find his allies on Mumsnet. It is telling that the lax content moderation policy and tacit approval of hate speech has turned the parenting platform into an echo chamber for anti-transgender advocates.

In 2018, the website introduced a new, stricter content moderation policy, declaring that “Mumsnet will always stand in solidarity with vulnerable or oppressed minorities.” Mumsnet moderators may now remove potentially harmful or offensive comments, for example, posts that include “trans-identified male”, “Cis” (cisgender, represent someone who is not transgender), and “TERF” (Trans-exclusionary radical feminist) will be deleted by moderators. Nonetheless, the new policy has generated a considerable amount of controversy, as some users believe that words like “Cis” do not normally have an insulting implication. The simultaneous banning of the terms “trans-identified male” and “cisgender” has led to many questioning that Mumsnet’s new moderation principle creates a false equivalence between the behavior of transgender users and anti-trans users.

While the introduction of new policies has been instrumental in the reduction of anti-trans speech, it has not eradicated the pervasive transphobia fostered by the old rules. From a forum originally created for parenting to a swamp of transphobia, from pro free speech to prohibited terms, we cannot help but ask: Where is the line between free speech and hate speech on social media platforms?

Free Speech and Hate Speech

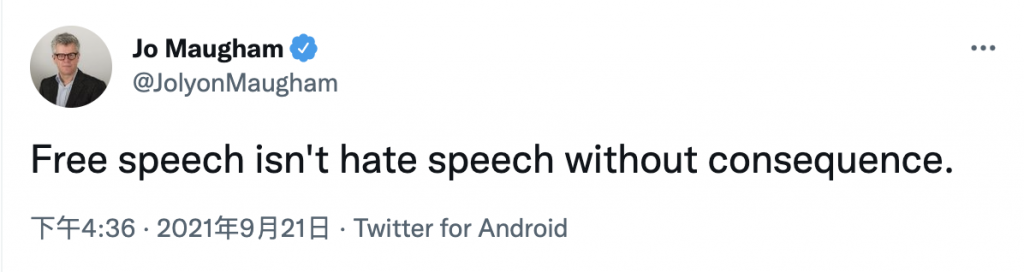

The case of Mumsnet reveals that there can often be a conflict between free speech and hate speech on social media platforms. Freedom of speech usually refers to the right of users to express their opinions on social media platforms, but only if these opinions are in accordance with national laws as well as platform norms; freedom of speech does not mean that anything can be said. Jo Maugham, a British barrister had posted a tweet on Twitter saying, “Free speech isn’t hate speech without consequence.” It’s like as citizens, we all have the right to drive on the road, but that does not mean we are free to break traffic rules or cause trouble on purpose.

In September 2021, social media influencer Justin Hart announced that he had filed a lawsuit against social media giants Facebook and Twitter because he believed the platforms violated his First Amendment right to free speech in the U.S. Constitution. He claims that Facebook and Twitter have repeatedly suspended his account over the past year for sharing what he calls “data” and “scientific research” about Covid-19.

However, the fact is that private companies like Facebook, Twitter and YouTube can set terms and conditions for those who use their platforms. In the case of social media, you must explicitly agree to comply with these terms in order to be allowed to use it – in other words, by using these platforms you are also implicitly agreeing to their censorship policies and content moderation policies.

To borrow a classic quote from philosopher Karl Popper, “in order to maintain a tolerant society, the society must be intolerant of intolerance.” This paradox illustrates the connection between free speech and hate speech on social media platforms, namely that the two are both coexistent and contrary to each other. But in any case, in order to maintain a fair and healthy atmosphere on social media platforms, the role of content moderation is crucial, as it acts as a restraint, or ” intolerance”.

The Future of Platform Content Moderation

The example of Mumsnet is another warning that when a platform lacks a proper content moderation policy, the platform can evolve into a breeding ground for extremists. While companies like Facebook, Twitter, and others have long sought to automate content moderation through artificial intelligence, human content moderators are still at the core, because human have social, cultural and political knowledge, and also cognitive abilities. Therefore, automated moderation is unlikely to replace human moderation, but it can serve as an effective aid and assistance. As Ruckenstein and Turunen (2020) suggest, the machine can rely on its accurate and rigorous algorithms and logic to assist the platform in doing the basic “cleaning work”, while the moderator can be freed up to handle more challenging and controversial work, thus enabling human-machine collaboration.

Conclusion

Freedom is never absolute, and any form of freedom must be limited to a certain degree in order for society as a whole to function effectively and maintain order and stability, and this theory is the same when applied to the social media platform environment. Whether it involves manual or automated moderation, an effective content moderation policy can bring the most critical protection to the harmony and discipline of the platform. Conversely, the lack of moderation policy may allow extremists or even terrorists to publish harmful comments under the banner of “freedom of speech”.

References

Ruckenstein, M., & Turunen, L. L. M. (2020). Re-humanizing the platform: Content moderators and the logic of care. New Media & Society, 22(6), 1026–1042. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444819875990

Gerrard, Y., & Thornham, H. (2020). Content moderation: Social media’s sexist assemblages. New Media & Society. 22. 1266-1286. 10.1177/1461444820912540.

Gillespie, T. (2020). Content moderation, AI, and the question of scale. Big Data & Society. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951720943234

Woods. (2021). Obliging Platforms to Accept a Duty of Care. In Martin Moore and Damian Tambini (Ed.), Regulating big tech: Policy responses to digital dominance (pp. 93–109).

Mumsnet. (2022). About us. Mumsnet. https://www.mumsnet.com/i/about-us

Roberts, S. (2019). 2. Understanding Commercial Content Moderation. In Behind the Screen: Content Moderation in the Shadows of Social Media (pp. 33-72). New Haven: Yale University Press. https://doi-org.ezproxy.library.sydney.edu.au/10.12987/9780300245318-003

Vincent, J. (2019). AI won’t relieve the misery of Facebook’s human moderators. The Verge. https://www.theverge.com/2019/2/27/18242724/facebook-moderation-ai-artificial-intelligence-platforms

Newton, C. (2020). Facebook will pay $52 million in settlement with moderators who developed PTSD on the job. The Verge. https://www.theverge.com/2020/5/12/21255870/facebook-content-moderator-settlement-scola-ptsd-mental-health

Morgan, J. R. (2021). Mumsnet: How Poor Moderation Created a Transphobic Swamp. An Injustice. https://aninjusticemag.com/mumsnet-how-poor-moderation-created-a-transphobic-swamp-adf391ccf9fc