The rapid development of social media provides a diverse platform for people to express themselves freely and allow people to exchange information and ideas with others. However, freedom of expression can also be taken advantage of, resulting in hate speech. In the past two years, the outbreak of COVID-19 increased racism online speech on social media. An increase in online hate speech is exacerbating racial tensions and racial hatred.

What is Hate Speech?

The council of Europe defined Hate Speech as:

many forms of expressions that advocate, incite, promote, or justify hatred, violence, and discrimination against a person or group of persons for a variety of reasons.

Online Hate Speech

Online Hate Speech is a type of speech that takes online with the purpose of attacking a person or a group based on their race, religion, ethnic origin, sexual orientation, disability, and/or gender.

Compared to hate speech offline, online hate speech differs in the nature of the interactions in which it takes place; it occurs in the virtual environment, making the internet users more anonymous which makes them feel less accountable for their behaviors, then leads to more hateful online speech, these hateful speeches can evolve, peak, and fade very quickly. (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, 2021).

In recent years, there are many incidents have shown that how online hate speech led to violence. In France, on 16 Oct 2020, a French teacher called Samuel Paty was beheaded by an Islamist. In a class on freedom of expression, he showed students Charlie Hebdo’s cartoons depicting the Islamic prophet Muhammad, while one of the cartoons presented an image of the prophet Muhammad naked with his genitals exposed. This triggered an online hate campaign and then lead to murder. In America, on 6 Jan 2021, Donald Trump’s supporters stormed U.S. Capitol to protest the outcome of the 2020 election, causing deaths and injuries. Many of these pro-trump insurrectionists used Facebook and other social media platforms to plan their attacks. In recent years, online hate speech is rising in many countries and in different social media platforms. An increase in hate speech led to the rise in violence and discrimination both online and offline.

Racist hate speech online

As social media have come to dominate socio-political landscapes in almost every corner of the world, new and old racist practices increasingly take place on these platforms. (Matamoros-Fernández & Farkas, 2021). Social media has been manipulated as a tool to spread racism, fake news, and hate speech. England football players Bukayo Saka, Jadon Sancho, and Marcus Rashford suffered racist abuse online after they are missing penalties in England’s Euro 2020 final defeat to Italy. A man posted racist comments on his Facebook about these three football players. Online trolls like to post hate messages in the form of abusive comments mentioning ethnicity, skin color, or emojis to get attention and spread racism.

During the COVID-19 outbreak, according to the report from Ditch the Label, between 2019 and mid-2021, on average there was a new post about race or ethnicity-based hate speech every 1.7 secs.

The ethnicity-based and racist hate speech rose by 28% in the UK and US. There are 50.1 million discussions about racist hate speech at that time. Anti-Asian hate speech increased by 1662% in 2020. (Ditch the Label, 2021).

Donald Trump’s “Chinese virus” Tweet incited racial hatred

Figure 1. Donald Trump’s tweet mentioned the “Chinese virus”. (The Atlantic, 2020).

On 16 March 2020, Donald Trump used the term “Chinese virus” to refer to the coronavirus for the first time on social media, exacerbating the tensions between the two nations. Donald trump’s inflammatory rhetoric incited more anti-Asian content on Twitter.

According to the executive director of the World Health Organization (WHO) health emergencies Programme Mike Ryan’s response to Donald Trump’s used term “Chinese virus”:

“Virus knows no borders and they don’t care about your ethnicity, the color of your skin, or how much money you have in the bank. So it’s important we be careful in the language we use leads to the profiling of individuals associated with the virus.” (CNBC,2020).

Besides, Ryan stated that people didn’t call it the North American flu when 2009 (HIN1) pandemic started in North America. Therefore, Ryan appealed to avoid connecting Viruses with any regions.

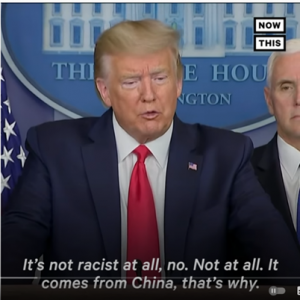

“It’s not racist at all”

Figure 2. Trump’s response to his use of the “Chinese virus”. (Youtube, 2020).

However, when a reporter asked about his use of “Chinese virus” to refer to the Coronavirus, he said:

“It’s not racist at all. It comes from China. I want to be accurate.”

Donald Trump dismissed that his use of the term “Chinese virus” is racist. He claimed that the virus did originally find in China. In his point of view, he didn’t have any racist intentions in this case. Matamoros-Fernandez (2017) stated that platformed racism evokes platforms as amplifiers and manufacturers of racist discourse. As a former president in America and also as a public figure, his language use in every speech or expression online and offline could be highly influential in the social and political worlds. His uses of sensitive and controversial words can quickly incite and exacerbate existing racial hatred and racial tensions, it can trigger more and more hate speech online and even violence offline.

More politicians, journalists, and other online users are still calling Coronavirus “Chinese virus” or other variants of this term such as “Chinese flu” and “Wuhan flu”.

In the weeks after Donald Trump tweeted about the “Chinese virus”, racism and attacks against Asians, especially Chinese have dramatically increased. Racist hate speech spreads online into real life.

“Use of terms like “Chinese virus” by the media and political leaders is unlikely to change a person’s beliefs or attitudes. But it can trigger negative stereotypes that can heighten prejudice and possibly even incite incidents of hate.” (Bushman, 2022).

During the COVID-19 pandemic, many Chinese students and immigrants in foreign countries suffered attacks and hate speech from racists. From being coughed and spit in their faces when they went out and verbally harassed to physical attacks, there are uncountable cases that happened during the pandemic.

On social media platforms, Donald Trump’s “Chinese virus” Tweet rose the anti-Asian hashtags Twitter. A study from the University of California, San Francisco examined nearly 700000 tweets containing a million hashtags to see whether Donald Trump’s use of the term “Chinese virus” may lead to the rise of Anti-Asian language uses on Twitter.

From the study results, researchers found that users who used #chinesevirus hashtags were more likely to use other racist tags. Besides, there are 19.7% of 495289 #covid19 hashtags showed Anti-Asian sentiment, compared with 50.4% of #chinesevirus hashtags. The results of the study clearly presented language matters when naming diseases. The expressions of “Chinese” or “Wuhan” virus which is problematic because it connects the infection with an ethnicity. It can trigger more hate speech about negative stereotypes and racial hatred online.

Is there Freedom for online hate speech?

On social media platforms, different countries have different attitudes and policies toward online hate speech.

In 2017, Germany passed a bill requiring social media platforms to delete illegal hate speech, slander, and other false content within 24 hours of receiving a notification. Ethnic discrimination, advocacy of Nazism, and denial of the Holocaust are illegal.

Similarly, in France, extreme hate speech needs to be removed forcibly, and social media platforms such as Facebook need to provide the user information and IP addresses of online hate speech at the request of the court for investigation.

In America, U.S. law is relatively tolerant of hate speech. The First Amendment of the United State Constitution protects the right to freedom of religion and freedom of expression from government. The First Amendment doesn’t force those social media platforms from preventing their restrictions on hate speech.

In the digital world, people are allowed to share and post their speech and comments anonymously. In contrast to the traditional media, there is no effective restraint on hate speech, the challenge of regulation of online hate speech is the lack of editorial oversight.

However, the prevalence of hate speech is dependent on the sample of content that users view on social media sites. To regulate and monitor hate speech, social media platforms usually take action by removing content when it is identified as hate speech and sending warning notifications to those users, restricting their behaviors and activities on the platform or even banning them.

International communities all have duties to monitor and regulate the spread of hate speech online. The regulation of online hate speech requires hardening the lines between freedom of speech and hate speech. Online hate speech cannot be normalized as free speech because when it goes extreme, it could be used as a social or political tool to spread racial hatred, leading to violence.

Moreover, these social media platforms play an important role in the lives of citizens. The attack on Capitol Hill in 2021 demonstrated how online hate speech on platforms can be manipulated as a political tool to incite violence, leading to death and injuries. In response to this event, Twitter has banned Donald Trump’s account due to his incitement of violence. These social media sites such as Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook all have relative guidelines towards hate speech and how to report hate speech anonymously. However, there is one big challenge of regulations of online hate speech is that the definitions of hate speech are fuzzy and vary on different platforms so that it’s not apparent to identify the hate speech, those social media sites only regulate hate speech based on their independent reports from users.

Overall, social media sites provide an online platform for freedom of expression, on the other hand, increases of hate speech are rapidly growing. Protected by Internet anonymity, extremists share and post hateful content on the platforms wildly. The virtual environment let users more anonymous and easier to express hate or other abusive behaviors. Hate speech can spread very quickly. When hate speech goes extreme, it turns into racial hatred and real-life violence. Especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, anti-Asian hate speech is rising on different social media platforms and many of them led to the violence. The case study of Donald Trump’s “Chinese virus” Tweet demonstrated how Donald Trump incited racial hatred and increased racist hate speech online by using unappropriated and unresponsible expressions to connect the virus with ethnicity. The online platform is used as a political tool to incite violence and exacerbate racial tensions. Avoiding keeping increasing hate speech online, all social platforms have duties to regulate and monitor the online environment.

Reference

Bushman, B. (2022). Calling the coronavirus the ‘Chinese virus’ matters – research connects the label with racist bias. Retrieved from: https://theconversation.com/calling-the-coronavirus-the-chinese-virus-matters-research-connects-the-label-with-racist-bias-176437

Consumer News and Business Channel. (2020). WHO officials warn U.S. President Trump against calling Coronavirus the “Chinese Virus”. Retrieved from:

Ditch the Label. (2021). Uncovered: online hate speech in the Covid Era. Retrieved from:

https://www.ditchthelabel.org/uncovered-online-hate-speech-in-the-covid-era/

Gaspar,G., Djeckmann A. & Neus, A. (2021). Leaders of Tomorrow Urge Social Media Companies to Fight Hate Speech. [Image]. Retrieved from: https://symposium.org/leaders-of-tomorrow-urge-social-media-companies-to-fight-hate-speech/

Matamoros-Fernández, A. (2017) Platformed racism: the mediation and circulation of an Australian race-based controversy on Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube, Information, Communication & Society. Retrieved from:

Matamoros-Fernández, A., & Farkas, J. (2021). Racism, Hate Speech, and Social Media: A Systematic Review and Critique. Television & New Media, 22(2), 205–224. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527476420982230

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. (2021). Addressing hate speech on social media: Contemporary Challenges. Retrieved from: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000379177