Introduction

Workplace surveillance is never a new story, but its explosion during the epidemic times is far beyond our imagination. Work from home not only shifts our workplace from the physical world to the digital void of Zoom meetings and Slack channels, but also opens the door to more intrusive monitoring in employee’s home and devices. According to research in UK on over 2000 companies, one in five firms had started using electronic tracking measures to monitor employee’s online activity as of December 2020 (Hughes, 2021). The demand for employee monitoring software only trends upwards in 2021, with a 71% leap in global demand in December compared with the pre-pandemic average (Migliano & O’Donnell, 2022).

Employers have moved beyond “panic-buying” of remote surveillance technologies during the outbreak of the pandemic to strategic planning of long-term use of monitoring technologies in work environment. With the surge of remote work, employers are incentivized to monitor employees to minimize their risk and liability to third parties, prevent leakage of confidential information, and more often, improve productivity (Masoodi et al., 2021). Moreover, emerging technologies boost the trend of analysing employee’s digital performance as a mean of manpower management. Webcam surveillance, keyboard monitoring, facial recognition and GPS tracking are some of the common tracking technologies that can be executed with just a click (Masoodi et al., 2021).

This blog will first examine different types of behaviour tracking techniques with two monitoring software, Controlio and Sneek, as the case studies. Each software has a remarkable increase of users during the first lockdown, with number tripled in Controlio (Wood, 2020) and five-fold in Sneek (Jones, 2020). The author will then elaborate on the implications and challenges of accelerating workplace surveillance after the inevitable shift to remote working and the integration of Artificial Intelligence in productivity management. Potential threats on employee’s digital privacy at work will be highlighted. The blog will be concluded with possible ways to fight against the uncontrollable expansion of workplace surveillance.

Big Brother Is Watching You: Controlio & Sneek

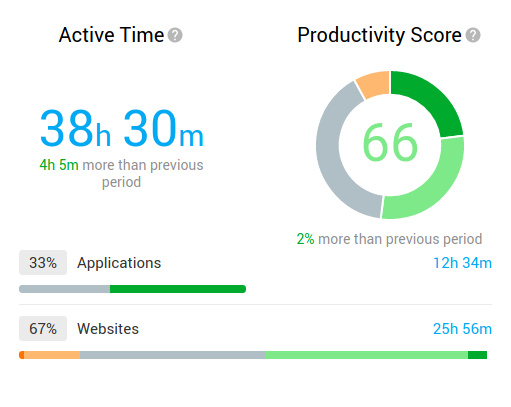

Controlio is an employee tracking software focusing on desktop and keyboard activity monitoring (Controlio, 2021). The software provides screen recording function, which allows employer to record, check and download all the screen activities in employee’s computer. All the tracked activities are automatically categorized into various aspects, such as business, communication, or design, etc. Employee’s time spent on different categories will be recorded on the dashboard of the software. Other than desktop monitoring, behaviour rules can be created by employer to restrict employees from accessing certain websites or downloading specific software. Employer will receive alerts if any employee has broken the rules. In addition, keystrokes logging allows employer to record keys typed by the worker, regardless of whether they are writing an email or typing in a password.

With vast amount of employee’s data in the system, the software can instantly analyse the performance of every employee and come up with a “productivity score”. The software will record the time when the employee is idle, active, productive, neutral, or distracted, according to their keyboard and mouse activity and the applications used. Employer can overview the productivity ranking and active time of employee on the dashboard. While some other software measures distraction by tracking the frequency of employee “switching between applications” (Masoodi et al., 2021), Controlio allows the employer to label the nature of application and websites. It is also worth noting that the software is capable of covert surveillance.

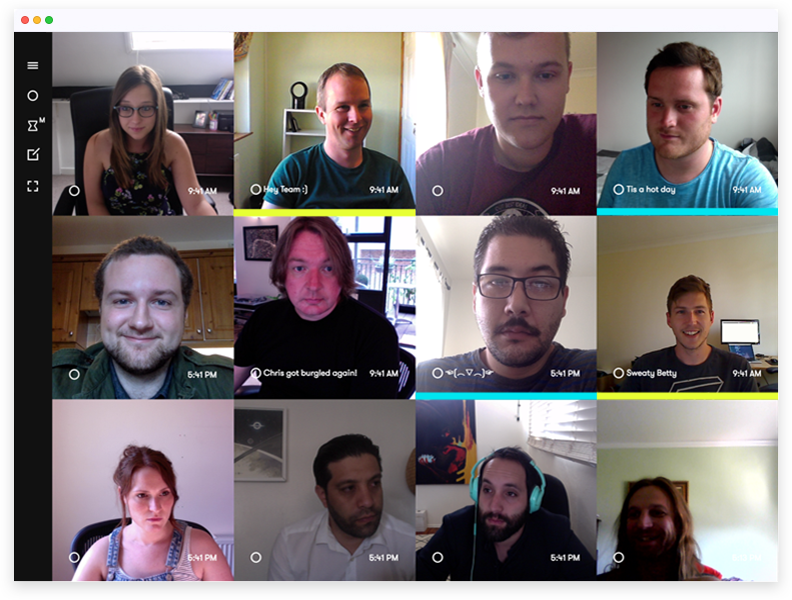

On the contrary to Controlio, Del Currie, cofounder of Sneek, told Insider that the software is designed to re-create the office atmosphere where you can see your co-workers working together with you (Holmes, 2020). The software takes pictures of employee with the laptop’s webcam between intervals of one minute to five minutes. Anyone in the chat room can start an instant video call by clicking on other’s picture (Sneek, 2016).

Implications and challenges

These two examples are just a sneak peek of thousands of workplace surveillance software in the marketplace. Nevertheless, some implications and challenges on the digital right of employee can already be observed from these cases, including the extent of consent surveillance, employee’s level of control over personal data, purpose of surveillance and power imbalance on digital privacy.

The Extent of Consent Surveillance

Despite the capability of covert surveillance in Controlio, Section 20 (3)(a) of the Workplace Surveillance Act in Australia explicitly opts out its use for the aim of tracking worker’s productivity. Still, employer is permitted to install any electronic surveillance with 14 days prior notification to employee and the obligation to state in the company policy (Frayne, 2022). Does that mean employee’s productivity will increase with a consent surveillance? Research has illustrated the negative correlation between employee’s levels of perceived workplace monitoring and attitude towards the surveillance systems (Riso, 2020), which means the higher the degree of monitoring is observed by the workers, the more they hate the system. Unfavourable attitude towards excessive workplace surveillance leads to high level of stress, diminished trust in management, adverse social relation in workplace and higher chance to engage in deviant bahaviours such as being absent, late or less proactive (Masoodi et al., 2021). Martin, Wellen and Grimmer’s research on relationship between Australians’ perceived degree of workplace surveillance and counterproductive work behaviours (CWB), such as withholding their effort or disobey the management, has further proven that more invasive they view workplace surveillance, the more they engaged with CWB (Martin et at., 2016).

Employee’s Level of Control over Personal Data

The degree of control over personal data is one of the key concerns of employee under workplace surveillance. Under screen recording activity and keystroke logging in Controlio, employees have no control over the data generated by their own activities. Although safety of the user information is promised by Andrew Makhanev, the project manager of Controlio, who mentioned to ABC news that they did not sell the user’s data stored by the company, which is situated in New York, for half a year to any third part, he pointed out that only customer, i.e. employer, have access to these information (Wood, 2020). A study in America found that when employees feel that they are powerless in controlling over the data that is collected by their employers during the surveillance process, they are more prone to deem unfair in work procedures, which further lower their trust on top management and commitment on the organization (Chory et al., 2016).

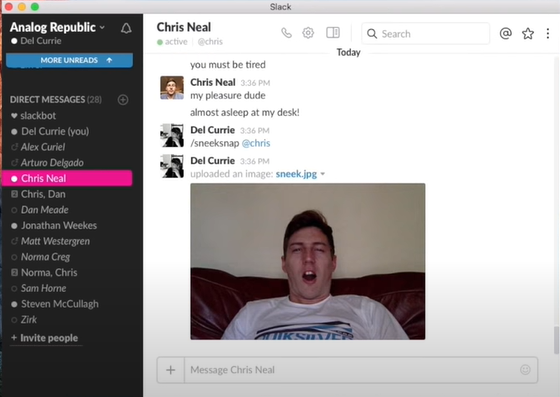

Being always ready for video call and work in front of the gaze of co-workers exerts tremendous mental stress on workers, not to mention the lack of control over the use of image. Sneek provides the function of “Sneek Snap”, which allows user to capture an image of their colleagues or employees and send out through Slack channels or google (Sneek, 2016). No warning in advance, so the photograph could be you doing anything – smelling your hair or picking your teeth. Ball and Margulis’s (2011) study has again proven that employees with lower control over the surveillance will be more likely to have higher stress level.

Purpose of Surveillance and Data Collection

Being spy without a legitimate reason is worse than living in a digital prison – even prisoners know their charges. The purpose of workplace surveillance is deemed to be crucial when it comes to employee’s sense of intrusiveness of certain technology, especially in public sphere. Employees are prone to dislike certain monitoring technology if they do not observe a clear purpose for that surveillance measure (Masoodi et al., 2021). According to a study in Canada, public servants and citizens deem that monitoring physical activity is more intrusive and unreasonable than digital surveillance (Charbonneau, 2020). Webcam surveillance in Sneek is viewed as more excessive and unreasonable in terms of tracking performance or productivity. With the technology of facial recognition, further privacy concern lies on the usage of video data including facial expression, eye movements and tone of voice. Global companies such as Microsoft and Amazon have already applied machine-learning algorithms to analyse the body movements and the quality of communication (Masoodi et al., 2021).

Another concern on surveillance is the bias of algorithmic intelligence driven system over employee’s work performance. Most of the time, employees are not informed with how their productivity is being assessed. For example, social networking sites are labelled as distraction in Controlio. However, many occupations including marketing, design, and sales require workers to access these platforms for data collection and communication purpose. Furthermore, creativity can hardly be measured by a quantifiable factor. The report published by European Union on electronic workplace surveillance pinpointed that enhanced internet monitoring brings negative effect on employee’s creativity and autonomy (Ball, 2021).

Power Imbalance on digital privacy

One may argue that consents are given by employees prior the installation of surveillance software. But let’s be honest: how many employees dare to say no to their bosses? Electronic Frontier Foundation commented that choosing between intrusive monitoring and joblessness does not really provide choices for most (Cyphers & Gullo, 2020). Employees often agree to these surveillance measures in order to keep away from potential consequences. The asymmetry of information further deprives worker’s bargaining power on promotion, salary adjustment and even dismissal. Software like Controlio and Sneek performs a 24/7 continuous surveillance over workers’ device, which create massive amount of records on every employee. It is impossible for employees to fully understand the range of the information collected and controlled by the employer (Masoodi et al., 2021).

Some also share concern on the influence of workplace surveillance over workers’ efforts on organizing union. Having a webcam that watching you all day can deter you from chit-chating with co-workers, not to mention organizing collective actions to subvert the management. Workers are at risk of being monitored on their communication with colleagues, thus cooling down possible union activity. In addition, employers gain imbalance advantages in suppressing an organizing drive, such as revenge on union supporters (Garden, 2018). In September 2020, Amazon was exposed in committing secret monitoring over Flex drivers’ social media pages to identify workers “planning for any strike or protest against Amazon” (Gurley, 2020).

How to fight against accelerating workplace surveillance?

Individual Resistances

Same as the high school kids who try to be unseen from the eyes of teachers, workers also play active role to go invisible quietly under the stringent surveillance system. Software imitating computer activity is used to trick the monitoring system on the productivity record. For example, Move Mouse, a software that moves the cursor automatically, has been largely downloaded after the first lockdown as reported in The Telegraph (2020). However, the management could interpret such actions as justification of higher degree of surveillance, leading to a vicious cycle (Anteby & Chan, 2018). This is where the government should step in and review the outdated legislation.

Legislation Review and Greater enforcement

According to Goggin (2019), right to privacy is not laid down in the Australia Constitution. Workplace surveillance is neither covered in The Privacy Act 1988, which includes 13 Australian Privacy Principles that regulate government and private sector players in processing personal information. In New South Wales, Workplace Surveillance Act 2005 bounds the employer’s behaviour in monitoring employees, including phone conversations (Office of the Australian Information Commissioner, n.d.). However, Controlio is a case in point that the privacy laws are outdated in protecting employee’s right at workplace from the emerging surveillance technology. The software can be installed without noticing employees, and the user data is stored in United States, where the Australian privacy laws may not be able to cover it (Frayne, 2022). A greater enforcement and a comprehensive review on the privacy laws can draw clear line on unreasonable monitoring practices that should be banned or restricted in order to protect employee’s shrinking digital right at workplace in the pandemic era.

Conclusion

Emerging technologies support more intrusive and accurate workplace surveillance measures, which have been explosively expanded during the pandemic. Controlio demonstrates the extensive monitoring on desktop and keyboard activity while Sneek illustrates the dystopian webcam surveillance that advocates “team work” environment. The rising concerns on ethics and power imbalance between employers and employees ring the alarm on workplace digital right. Cooperative forces from individuals and government are required to change the situation.

References

Anteby, M., & Chan, C. K. (2018). A Self-Fulfilling Cycle of Coercive Surveillance: Workers’ Invisibility Practices and Managerial Justification. Organization Science (Providence, R.I.), 29(2), 247–263. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2017.1175

Ball, K. (2021). Electronic Monitoring and Surveillance in the Workplace. Publications Office of the European Union. doi:10.2760/5137

Ball, K. S., & Margulis, S. T. (2011). Electronic monitoring and surveillance in call centres: A framework for investigation. New Technology, Work and Employment, 26(2), 113-126. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-005X.2011.00263.x

Boland, H. (2020, August 11). Meet the workers fighting back against bosses who spy on them while working from home. Retrieved April 8, 2022, from https://www.telegraph.co.uk/technology/2020/08/11/meet-workers-fighting-back-against-bosses-spy-working-home/

Charbonneau, É, & Doberstein, C. (2020). An empirical assessment of the intrusiveness and reasonableness of emerging work surveillance technologies in the public sector. Public Administration Review, 80(5), 780-791. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13278

Chory, R. M., Vela, L. E., & Avtgis, T. A. (2015). Organizational Surveillance of Computer-Mediated Workplace Communication: Employee Privacy Concerns and Responses. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 28(1), 23–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10672-015-9267-4

Controlio. (2022). Attendance. Retrieved April 8, 2022, from https://controlio.net/attendance.html

Controlio.net (Producer). (2021, July 14). Controlio Overview [Video file]. Retrieved April 8, 2022, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hn-Wy9W5w_4

Cyphers, B., & Gullo, K. (2020, August 18). Inside the invasive, secretive “Bossware” tracking workers. Retrieved April 8, 2022, from https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2020/06/inside-invasive-secretive-bossware-tracking-workers

Frayne, A. (2022, March 16). Can your boss use electronic surveillance to monitor you when you work from home? Retrieved April 8, 2022, from https://www.mondaq.com/australia/employee-rights-labour-relations/1171560/can-your-boss-use-electronic-surveillance-to-monitor-you-when-you-work-from-home

Garden, C. (2018). Labor organizing in the age of surveillance. Retrieved April 8, 2022, from https://digitalcommons.law.seattleu.edu/faculty/814

Goggin, G., Vromen, A., Weatherall, K., Martin, F., & Sunman, L. (2019). Data and digital rights: recent Australian developments. Internet Policy Review, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.14763/2019.1.1390

Gurley, L. K. (2020, September 2). Inside Amazon’s secret program to spy on workers’ private Facebook groups. Retrieved April 8, 2022, from https://www.vice.com/en/article/3azegw/amazon-is-spying-on-its-workers-in-closed-facebook-groups-internal-reports-show

Holland, P. J., Cooper, B., & Hecker, R. (2015). Electronic monitoring and surveillance in the workplace. Personnel Review, 44(1), 161–175. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-11-2013-0211

Holmes, A. (2020, March 23). Employees at home are being photographed every 5 minutes by an always-on video service to ensure they’re actually working – and the service is seeing a rapid expansion since the coronavirus outbreak. Retrieved April 8, 2022, from https://www.businessinsider.com/work-from-home-sneek-webcam-picture-5-minutes-monitor-video-2020-3

Hughes, O., Staff, T., Matteson, S., Kaelin, M., Wallen, J., Miles, B., & Stone, B. (2021, February 02). Bosses are using monitoring software to keep tabs on working at home. privacy rules aren’t keeping up. Retrieved April 8, 2022, from https://www.techrepublic.com/article/bosses-are-using-monitoring-software-to-keep-tabs-on-working-at-home-privacy-rules-arent-keeping-up/

Jones, L. (2020, September 29). ‘I monitor my staff with software that takes screenshots’. Retrieved April 8, 2022, from https://www.bbc.com/news/business-54289152

Martin, A. J., Wellen, J. M., & Grimmer, M. R. (2016). An eye on your work: How empowerment affects the relationship between electronic surveillance and counterproductive work behaviours. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 27(21), 2635-2651. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2016.1225313

Masoodi, M.J., Abdelaal, N., Tran, S., Stevens, Y., Andrey, S. and Bardeesy, K. (2021, September). Workplace Surveillance and Remote Work: Exploring the Impacts and Implications Amidst Covid-19 in Canada. Retrieved from https://www.cybersecurepolicy.ca/workplace-surveillance

Migliano, S., & O’Donnell, C. (2022, February 11). Employee Surveillance Software Demand up 56% Since Pandemic Started. Retrieved April 8, 2022, from https://www.top10vpn.com/research/covid-employee-surveillance/

Nguyen, A. (2021, May 19). The constant boss. Retrieved April 8, 2022, from https://datasociety.net/library/the-constant-boss/

Office of the Australian Information Commissioner. Workplace Monitoring and surveillance. (n.d.). Retrieved April 8, 2022, from https://www.oaic.gov.au/privacy/your-privacy-rights/employment/workplace-surveillance

Riso, S. (2020). Employee monitoring and surveillance: The challenges of digitalisation. Publications Office of the European Union. https://www. eurofound.europa.eu/publications/report/2020/employee-monitoring-andsurveillance-the-challenges-of-digitalisation

Sneek. (2016, September 27). Sneek. Retrieved April 8, 2022, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M_V5VaIQqk0

Wood, P. (2020, May 21). These programs monitor your every keystroke as you work from home – and report back to your boss. Retrieved April 8, 2022, from https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-05-22/working-from-home-employee-monitoring-software-boom-coronavirus/12258198