1. Introduction

The Internet has increasingly influenced different social, economic, and cultural aspects of human life where associated emerging issues are managed and conducted following a set of rules for the Internet and associated digital technologies and platforms. These rules are referred to as governance that regulates effective use of the Internet and associated platforms, including civil and corporate society actors. This post explores the threats to privacy in a digital age. There is a growing concern among internet users in the United States regarding the federal policies and social media sites in terms of data privacy. Therefore, an improved governance system is required for protecting privacy in a digital age.

2. Right to Privacy

Simply, the right to privacy is a component of several legal systems that seek to limit governmental and private institutional actions that jeopardize persons’ privacy. According to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights by the United Nations(2022), no one is to experience arbitrary interference with their family, correspondence, home, and privacy and are not subject to be attacked upon their reputation and honor . Hence, the right to privacy includes the right to be left alone, the right to secrecy, and the ability to protect oneself from unwanted external interference or scrutiny (Mishra, 2019). In addition, individuals also have the right to take control over personal information and the manner they are used. Apart from that, an individual’s personality, dignity, and individuality are subject to be protected against unaccepted intervention. The right to privacy also provides control over personal decisions and intimate relationships.

Figure1:Right to Privacy

Image Source: Akmllp (2017)

The right to privacy ensures non-discrimination against personal situations such as sexuality, disability, and medical conditions. For instance, a person is not to be questioned unnecessarily upon their sexual orientation. It guarantees personal security and provides liberty of conscience. For instance, every person has the right to follow personal ethical and religious beliefs (Flew, 2018). It also allows having control over personal space and provides freedom from arbitrary invasion. However, the right to privacy can co-exist with the public right to know, use of susceptible information by security agencies to solve crimes, and accountability and transparency of the governmental and institutional decision making.

3. Perspectives on the Right to Privacy and Terms of Services

There are three perspectives associated with the concept of privacy where the privacy fundamentalists are strictly against the disclosure of personal information and are much concerned about privacy. The privacy pragmatists are people that believe the government and the institutions tending to use personal information are needed to be assured by the government upon ethical and meaningful use of data provided (Marwick & Boyd, 2019). In contrast, people who are least protective of their privacy, considering that benefits gained in exchanging personal information outweigh the threat of potential data misuse, are referred to as privacy unconcerned (Suzor, 2019). Therefore, the terms of services are an important factor in determining the extent to which the government or a business entity can access an individual’s personal information. These perspectives are reflected through the consents provided by the users when they accept the terms of services.

Though people seem concerned about their privacy, they do not behave accordingly. According to Marwick and Boyd (2019), it is referred to as the privacy paradox that blurred due to the diminishing differentiating line around consent. The terms of services are the governance documents presented to the users on the Internet or associated platforms by which users may provide consent to fetch various permissions to the intermediaries. This is the legal means to acquire permission to use data for different purposes. Usually, most internet platforms provide an ultimate cautionary to take the service through providing permission or leaving it. However, Botta and Wiedemann (2019) mentioned that the online platforms often demonstrate terms of services that are incomprehensible for the lay users. This questions the governance in terms of transparency maintenance, where a basic requirement for a company is to operate ethically and legally. According to Suzor (2019), people agree with the platform via a clause that sets out a basic rule to limit access or terminate the access at any time with no reason.

It can be threatening as it does not clarify or specify the actions upon which such rules to be applied. This results in a privacy imbalance marked by information asymmetry, where the online platforms gain unlimited power to bargain with their users. Business organizations often try to obtain a dominant position in the market by using these platforms by aggressively using consumer data. As a result, users may lose control over the manner their personal information is being used. It is important to consider the privacy, profiling, data analytics along government data-matching, and surveillance associated with digital rights (Goggin et al., 2017).

4. Case Study

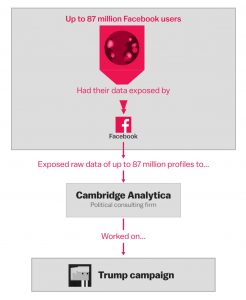

·Background

The Cambridge Analytical scandal, 2018, is a significant instance of privacy invasion where Christopher Wylie, as the Pink-hired whistleblower, exposed a large scale data reaping through Facebook quizzes for political purposes. The information was revealed to The Guardian, The New York Times. Christopher disclosed that Facebook sold millions of Americans’ data without their awareness to a firm, namely Cambridge Analytica, used to promote political agendas. Immediately before the story spread, Facebook barred Wylie, Cambridge Analytica, its parent firm SCL, and the researcher who obtained the data, Aleksandr Kogan, from the network. However, these actions were not enough and were unable to quell the fury of users, policymakers, privacy advocates, and media critics. Facebook’s stock price dropped instantaneously, and boycotts began. Zuckerberg was summoned to appear before Congress, a year of acrimonious worldwide arguments about consumer online privacy rights started. As a result, in 2019 Federal Trade Commission issued a $5 billion penalty on Facebook (Confessore, 2022).

Figure 2:Privacy Invasion

Image Source: Vox (2018)

·Breach of Privacy Rights

European Union states adopted the General Data Protection Regulation in 2016, which was legally enforced in 2018. It regulates the activities of the businesses and other institutions that use personal data from its users. It also enforced that online platforms need to allow users to give informed consent, which can be withdrawn. The law also enables consumers to be informed when their personal information is used. It is about a completely preventable problem that stems from a lack of accountability among the companies that process enormous amounts of personal data and a failure to secure informed consent (Mourby et al., 2018). A literal rule is known as “purpose limitation” is required to prevent unrestricted admittance to personal data. Sharing of data fuels the app economy — for example, maps that collect individual location details or communication apps that access the list of contacts, which may be appropriate. On the other hand, App developers should only gather data that can be demonstrated to be proportionate and essential for the claimed purpose of their service.

Consumers were astonished by the settings on their Facebook accounts, as evidenced by the outpouring of fury in response to the Cambridge Analytica discoveries. Default opt-in, often known as “consent-based on silence,” appeared unjustified. Consent rules under the privacy law must be clearly defined. According to the European GDPR, this must be freely supplied, unambiguous, specific, and informed. It specifies that wording should be clear and straightforward, that no unjust words should be used, and that separate consent should be granted for distinct data processing procedures (IT governance, 2022). It should be able to agree to one but refuse to agree to another. The terms and conditions cannot be interpreted as a contract that includes all of our interests and rights. The Constitution guarantees the right to privacy, and the Supreme Court’s landmark privacy decision reminds us that any intrusion into privacy must be justified and reasonable. There is also a requirement for obligations to satisfy proportionality and fairness standards regardless of the user’s consent. For instance, consents are not to be used as a legitimization of data collection for a specific purpose.

Clear standards will be required in the legislation for what corporations claim to be “legitimate interests,” which are presented as a substitute to consent. If individuals cannot realistically expect their data to be used in specific ways, or if doing so would violate their rights to meaningful signup, then the commercial interest should take precedence. Combining disparate databases, where data was originally obtained in different contexts and for multiple reasons, and creating sophisticated profiles of persons outside their permission, is not legitimate, appropriate, or essential. The Cambridge Analytica incident shows that implementing the substance and spirit of privacy regulation can be difficult. This pessimism, though, should only lead to tighter governance. A powerless regulation is significantly simpler to ignore during the enforcement stage and during the conformity stage. A powerful data protection body with defined rules and punitive powers will have a huge impact on the legal risk calculation of enterprises that provide services to common consumers (Casey, Farhangi & Vogl, 2019).

5. Increased Susceptibility to Privacy Invasion Due to Data Portability

The provision for consumers to be able to switch platforms for using their personal data has unlocked a wide array of vulnerabilities. Furthermore, the portability technology is far from perfect, and the users tend to fail to track their data across platforms (IT Governance, 2022). Data and privacy breaches are commonly associated with a business competition where consumer data are misused to fulfil business purposes (Strowel & Somaini, 2021). Though data obtained through market research and consumer feedback are used for business improvement purposes, the extent to which the information is used is regulated by this legislation. The GDPR enforces eight rights, one of which is the right to data accessibility or portability. It enables data subjects to obtain and reuse data that a data controller has on file for them. Consumers can store the data for personal use or transmit it to another data user. The data must be submitted “standardized, generally used, and machine-readable.”

The right applies to the personal information given by the user to the controller. Therefore, platforms like the Facebook data governance system have to recognize the proportion and the extent to which a user’s data is collected (Choi, Jeon & Kim, 2019). This does not just refer to users’ information to create an account, such as their names and addresses. It also relates to individual information gathered by corporations while observing a person’s behavior. Therefore, personal data may include browsing history or raw data processed from smart wearable devices and location and traffic data. A clear difference should be made between these personal data given to the collector and the additional information provided to the organization to make a user profile (Mourby et al., 2018). Whenever individuals implement their right to data portability, they do so without damage to any other right. After exercising the right to data portability, a data subject may keep using the data operator’s services, but this does not change the operator’s rights or obligations. Data portability does not immediately activate the right to deletion, and it does not affect the data’s original retention duration. As long as the controller is still performing operations, the subject in question can exercise their right.

6.Conclusion

In conclusion, the right to privacy comprises the right to be left alone, the right to secrecy, the ability to shield oneself from unwelcome external intervention or examination, and the right to determine which personal information to reveal and how it is used. The Cambridge Analytica issue demonstrates how difficult it can be to apply both the substance and spirit of privacy governance. On the other hand, this pessimism should only result in tougher rules. The privacy-related perspectives of the users also significantly influence their decisions on giving away personal information. Therefore, data portability has to be provided with greater emphasis while securing individual privacy rights. Data portability refers to an individual’s ability to access and reuse personal data across several platforms for their reasons. In the legislation, clear standards will be necessary for what companies claim to be “legitimate interests,” which are portrayed as a substitute for consent. If individuals cannot realistically expect their data to be used in certain ways, or if doing so violates their rights to informed consent, then corporate entities should take precedence.

References

Akmllp. (2017). Is our Private Life Really Private? – Right to Privacy. Retrieved from https://www.akmllp.com/insights/is-our-private-life-really-private-right-to-privacy/

Botta, M., & Wiedemann, K. (2019). Exploitative conducts in digital markets: Time for a discussion after the Facebook Decision. Journal of European Competition Law & Practice, 10(8), 465-478. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeclap/lpz064

Casey, B., Farhangi, A., & Vogl, R. (2019). Rethinking Explainable Machines: The GDPR’s’ Right to Explanation’Debate and the Rise of Algorithmic Audits in Enterprise. Berkeley Tech. LJ, 34, 143. https://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/berktech34&div=8&id=&page=

Choi, J. P., Jeon, D. S., & Kim, B. C. (2019). Privacy and personal data collection with information externalities. Journal of Public Economics, 173, 113-124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2019.02.001

Confessore, N. (2022). Cambridge Analytica and Facebook: The Scandal and the Fallout So Far. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/04/us/politics/cambridge-analytica-scandal-fallout.html

Flew, T. (2018). Platforms on trial. Intermedia, 46(2), 24-29. https://eprints.qut.edu.au/120461/

Goggin, G., Vromen, A., Weatherall, K., Martin, F., Webb, A., Sunman, L.& Bailo, F. (2017) In Digital Rights in Australia. Executive Summary and Digital Rights: What are they and why do they matter now? Sydney: University of Sydney.

IT Governance. (2022). The GDPR: Understanding the right to data portability. Retrieved from https://www.itgovernance.eu/blog/en/the-gdpr-understanding-the-right-to-data-portability

Marwick, A. & Boyd, d. (2019). Understanding Privacy at the Margins: Introduction. International Journal of Communication, pp. 1157-1165. https://web.s.ebscohost.com/abstract?direct=true&profile=ehost&scope=site&authtype=crawler&jrnl=19328036&AN=139171463&h=om1iv1yJKsiDoJwpzRkKAzYWMTitqa6U%2fBVmJSgZ4QEfNMt6PyFd2dO%2fnX%2bJWEC6Et%2bK%2bi2QKw3MVsaOKwLnoA%3d%3d&crl=c&resultNs=AdminWebAuth&resultLocal=ErrCrlNotAuth&crlhashurl=login.aspx%3fdirect%3dtrue%26profile%3dehost%26scope%3dsite%26authtype%3dcrawler%26jrnl%3d19328036%26AN%3d139171463

Mishra, N. (2019). Building Bridges: International Trade Law, Internet Governance, and the Regulation of Data Flows. Vand. J. Transnat’l L., 52, 463. https://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/vantl52&div=15&id=&page=

Mourby, M., Mackey, E., Elliot, M., Gowans, H., Wallace, S. E., Bell, J., … & Kaye, J. (2018). Are ‘pseudonymized data ways personal data? Implications of the GDPR for administrative data research in the UK. Computer Law & Security Review, 34(2), 222-233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clsr.2018.01.002

Strowel, A., & Somaini, L. (2021). The transparency of online platforms pursued by EU laws still needs Legal Design tools for empowering the users. A program for future research. Legal Design Perspectives: Theoretical and Practical Insights from the Field, 159. https://dial.uclouvain.be/pr/boreal/object/boreal%3A254387/datastream/PDF_01/view#page=159

Suzor, N. (2019). ‘Who Makes the Rules?’. In Lawless: the secret rules that govern our lives. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 10-24.

United Nations. (2022). Universal Declaration of Human Rights. United Nations – Peace, dignity and equality on a healthy planet. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights

Vox. (2018). The Facebook and Cambridge Analytica scandal, explained with a simple diagram. Retrieved from https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2018/3/23/17151916/facebook-cambridge-analytica-trump-diagram