Introduction

In today’s digital age, where people inevitably rely more and more on digital communications to conduct their social, economic and political lives, the human rights that people have outside the network should also be protected online. Alexandra Rengel found that the right of privacy can variously refer to the right to be left alone, the ability to protect oneself from unwanted access by others, the right to secrecy, control over personal information, protection of one’s personality, individuality, and dignity, and control over one’s intimate relationships or over aspects of one’s life (Flew, 2021, p. 76). This blog will discuss the different forms of threats to privacy that arise in the digital age, with China as the background.

Data breaches

While consumers are enjoying the various benefits of the rapid development of the internet, incidents of leakage, theft and trafficking of personal privacy information occur from time to time, and harassment and fraudulent calls and emails are still rampant, which become a common concern for the whole Chinese society and consumers at large. According to the Application Personal Information Leakage Survey Report released by the China Consumers Association in 2018, in the 5,458 valid questionnaires, 85.2% of respondents said they had experienced leakage of personal information. (2018).

According to a report by China Youth Daily, the data breaches of users’ information from Little Red Book (China’s answer to Instagram) led to 50 users being defrauded of a total of RMB 880,000 in 2017 (Li & Jiang, 2017). The investigation found that these victims all had online shopping experiences on Little Red Book, and they had received phone calls from people claiming to be “Little Red Book customer service” who said that they had purchased goods that needed to be refunded because of quality problems. After following the instructions of the “customer service”, the money from these users’ accounts was deducted. The “customer service” sent these victims their order numbers, the details of their delivery addresses, the products they purchased and even their logins and passwords of Little Red Book, so they did no doubt about the identity of the “customer service”. This showed that the fraudsters had almost all the personal information of the users in Little Red Book as well as their national ID information, which they were required to provide to Little Red Book when they registered their accounts.

(Little Red Book, a social media and e-commerce platform in China.)

The founder of YouXia.ORG Baichuan Zhang said, “If there is a massive data breach on online shopping platforms, the first possibility is that their systems are flawed and have been hacked; the second possibility is that insiders illegally peddle users’ personal information” (Li & Jiang, 2017). In response to this incident, Little Red Book did not acknowledge their responsibility for it and said they did not find any information leakage on the platform after internal verification and technical checks. However, the victims insisted that Little Red Book should compensate them for their losses as their personal information was only provided to this platform. Awkwardly, the reality is that in China it is often difficult to determine which part of the process went wrong after an information leak occurs, and the definition of liability and punishment is unclear, and the cost of obtaining evidence and defending users’ rights is high. In the end, due to the lack of evidence, Little Red Book was not punished in any way. Following this, in 2018, Little Red Book received complaints from users for the platform set their privacy settings to allow others to add them as friends by default and to view some of their personal information, resulting in information about what they follow on the platform and their interests being known to strangers. Because of this, Little Red Book was punished by the local market supervision bureau for violating the Consumer Rights Protection Law with a fine of RMB 50,000 (Pei, 2019).

It is clear from this case that Chinese government departments are very light on penalties for online platforms in terms of regulation, which can lead to frequent cases of leakage or infringement of users’ private information by online platforms. And in China, the founders and administrators of online platforms have not placed greater emphasis on protecting the privacy of their users. The CEO of Baidu Yanhong Li commented on the use of personal information at the 2018 China High-Level Development Forum, “I think Chinese people can be more open and less sensitive to privacy issues. If they are willing to trade privacy for convenience, which in many cases they are, then we can do something with the data” (Jiang, 2018). While the leak of 50 million users’ information from Facebook was in full swing and Mark Zuckerberg publicly apologised in several media, as the founder of Baidu which is China’s largest search engine, made such a statement, which was very unacceptable to Chinese netizens. Online platforms have access to users’ personal information, and they have duties and responsibilities to protect the information rather than attempting to exploit it for great gain. The new leader of Germany’s Social Democratic Party has called for rules to govern “digital capitalism”, stating that “we don’t accept that more and more internet platforms are becoming monopolists that don’t take responsibility for society” (Flew, 2019, p. 25). In addition, although each online platform has its terms and conditions, often these are full of loopholes. These terms and conditions always appear when registering a new user or signing up with a new service and the user can only continue with consent. However, almost nobody ever reads these, because not only are they usually written in dense legalese, but also there is no opportunity to negotiate the terms anyway. These terms and conditions are almost all very careful to promise nothing and reserve almost absolute discretion to the owner of the network (Suzor, 2019). This makes most users not even consider whether their personal information is at risk of being exploited, and they only remember these terms when they discover that their rights of privacy have been violated, but in many cases, these terms are not helpful to them in defending their rights. According to the Application Personal Information Leakage Survey Report, about one-third of respondents said they remain silent after their personal information was leaked, which may be a choice based on their inability to respond or an acceptance of the status quo after an ineffective response (2018). On the other hand, China is a developing country with a population of 1.4 billion and the citizens are not sufficiently aware of the importance of protecting their personal privacy on the Internet, especially those netizens without higher education and elderly netizens who are more likely to readily provide their personal information to various unsecured platforms for some convenience.

Ubiquitous surveillance

Everyone’s life is under data surveillance all the time, as people are tracked for records and preferences when browsing the web, every move monitored by cameras when working indoors, and are listened to and recorded by communications companies throughout their conversations with others in-calls…

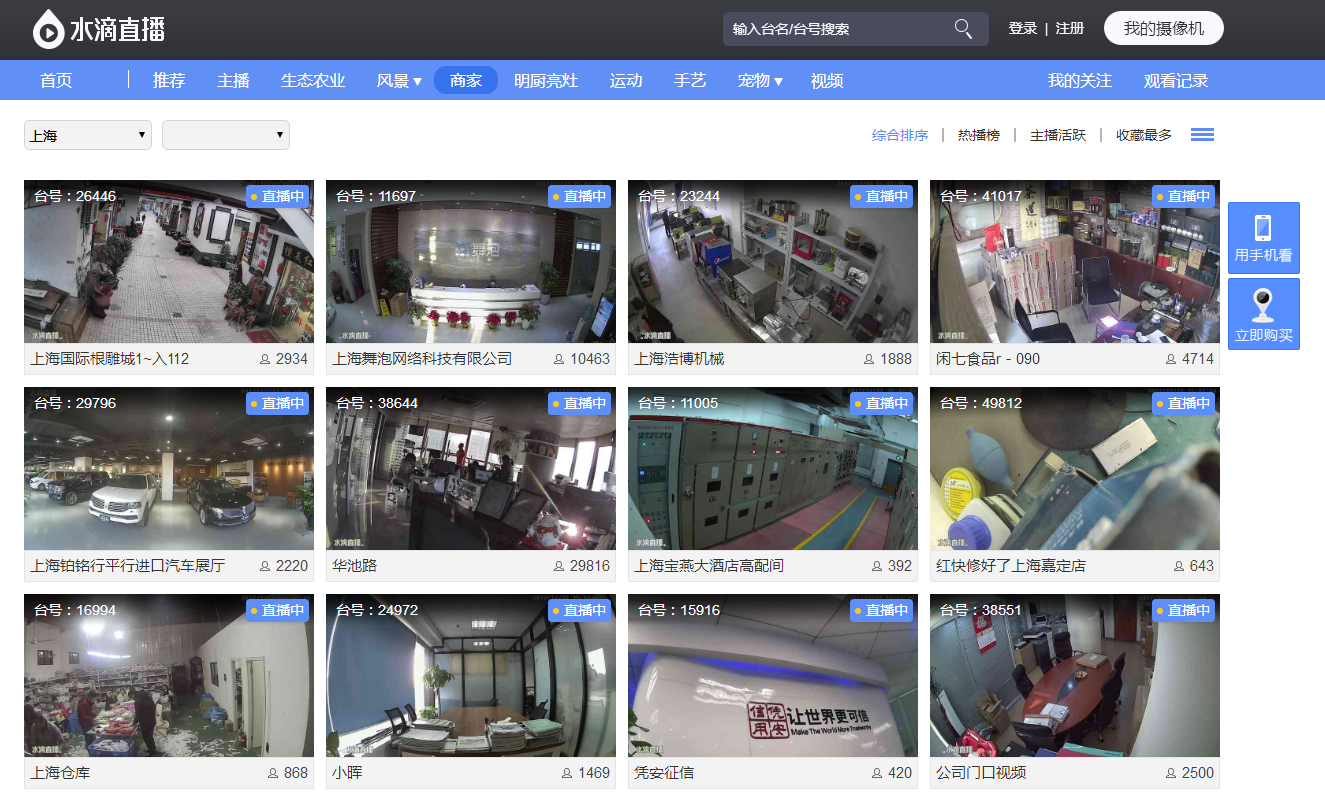

In December 2017, a girl exposed the gross invasion of public privacy of a webcast platform. She had visited several shops, including vegetarian restaurants, restaurants, snack bars and internet cafes. All these shops were installed with “360 Cameras”, through which the scenes inside these shops could be transmitted directly to “Waterdrop Live” in real-time for users to watch and comment on the people and their behaviours in the webcasts. Most importantly, most of the staff and customers were unaware of the live webcasts. Moreover, very few of the shops that the girl visited had posted live webcasting notices (Zhou & Cai, 2017).

(Waterdrop Live.)

Waterdrop Live is a live video lifestyle show platform owned by Qihoo 360 Technology Co. Ltd, provided instant live content from real users, covering entertainment, lifestyle, games, variety, sports and many other areas. It is not a standalone platform, as only those who have purchased a 360 Camera can do live webcasting, but everyone can watch all live content on Waterdrop Live. Those who purchased 360 Camera had done real-name registrations on the platform before they did webcasts, and at the same time, they had agreed to comply with the rules set by the platform, which include that the content webcasted by the user must be free of any private information about themselves or others and not break the law. However, the reality was that most users did not follow these rules. In order to gain attention and traffic, they exposed people’s privacy on the internet for others to watch and comment on. In the wake of public opinion, the Waterdrop Live platform was shut down that year and has never been opened again. However, it is worth noting that both the platform and the users who had webcasted others’ privacy were not punished, which is not fair to the victims at all. A Beijing lawyer said that compared to developed countries such as the United States, the current cost of defending the right to privacy in China is high, but the cost of breaking the law is low (2021). Because of this, more and more people are using illegal means to make huge profits and test the boundaries of the law, and the privacy rights of Chinese citizens have been trampled on for a long time. Especially with the later arrival of pinhole cameras, they can be hidden in any corner to spy on people’s privacy, including hotel rooms, massage parlours, public bathrooms and even on people’s satchels and shoe tops. Because they are so difficult to detect, this has allowed tens of thousands of people to become objects of voyeurism and masturbation as well as tools for profit without their knowledge.

In Korea, violations will be punished with fines of up to 50 million won (about RMB 300,000) if they install filming or photographing devices, including CCTV cameras, Internet-connected cameras, smartphones and wearable cameras at public bathhouses, restrooms and other places vulnerable to privacy violations (2017). However, according to Public Security Punishment Law in China, those who “spy on, take photographs of, eavesdrop on, or disseminate the privacy of others” are liable to a maximum penalty of 10 days’ detention and a fine of RMB 500. They are both Asian countries, but they differ so much in terms of the level of punishment for violating other people’s privacy. In this regard, China’s relevant laws must be amended and improved to ensure that citizens’ privacy is not infringed, which is crucial.

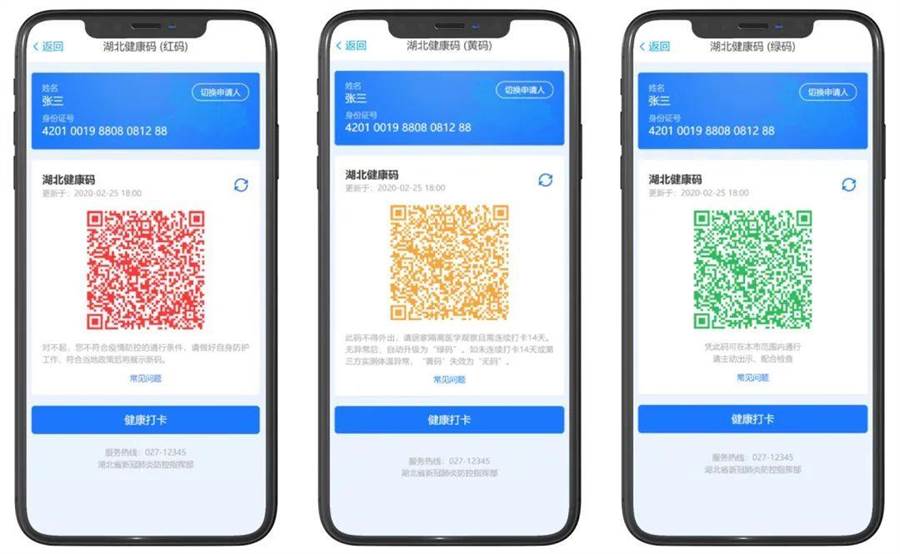

(Health Codes in Hubei.)

From 2020, the Chinese government has used a colour-based “health code” system to monitor people’s movements and prevent the spread of the coronavirus. People only are allowed to enter any public place if their QR codes are shown in green (Gan, 2020). Most citizens are not concerned that their personal information could be leaked or used because the information is collected by the government and they have full confidence in the government. Charles Mok, a lawmaker and tech entrepreneur in Hong Kong, said in an interview with VOA, “The problem is also with privacy concerns because the biggest worry is that once this (latest practice of using spatial data) is in place, it is very difficult to take away” (Huang, 2020). The Chinese government has enlisted the help of Alibaba and Tencent to host the health code systems on their popular smartphone apps Alipay and WeChat which are both ubiquitous and used by hundreds of millions of Chinese (Gan, 2020). It is actually difficult for citizens to know what will happen to this information in the codes when COVID-19 is over. These two internet giant companies could no longer be trusted by people if they are out of the hands of the government. This is because they have all been involved in scandals of leaking user information.

The likelihood of a particular path being pursued is contingent to some degree on the institutional culture and regulatory histories of nation-states… so there tends to be a stronger focus on legal remedies and the role of non-state actors and grassroots campaigning for change (Flew, 2019, p. 26). In the era of big data, the rights of privacy of Chinese people are threatened in various ways. With imperfect laws, Chinese netizens must first build and strengthen their awareness of self-protection of their privacy and insist on defending their rights when their privacy is infringed upon. Secondly, China’s internet giants need to set a good example by valuing the privacy rights of the users seriously, rather than doing what Yanhong Li said. The most important point is that China’s relevant laws must be improved. Those platforms that violate citizens’ privacy should be severely punished so that other platforms can consciously comply with protecting users’ privacy. It is worth mentioning that The Personal Information Protection Law was passed by China’s main legislative body, the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress, and went into force on November 1, 2021. This demonstrated the importance that the Chinese government was beginning to place on the protection of the privacy of its citizens.

Conclusion

In the age of data, while people enjoy the convenience of data, their rights of privacy are threatened to varying degrees. Data breaches and surveillance are happening all the time in China, and there is no way to avoid them. To face these issues, Chinese netizens need to raise their awareness of personal privacy self-protection and be brave enough to defend their rights; online platforms need to consciously abide by the rules and ensure the security of their systems while paying attention to the protection of users’ personal information; China’s laws on privacy security and punishment must be improved and, like other countries, severe penalties should be imposed for infringement of citizens’ privacy.

Reference List

- Flew, T. (2021). Issues of Concern. In Regulating Platforms (pp. 72–103). Polity.

- China Consumers Association. (2018, August 29). Application Personal Information Leakage Survey Report. Retrieved from China Consumers Association website: https://www.cca.cn/jmxf/detail/28180.html

- Li, C., & Jiang, F. (2017, June 14). Victim question: How did my information get leaked? Retrieved from China Youth Online website:

http://news.cyol.com/content/2017-06/14/content_16186291.htm - Pei, Y. (2019, March 2). 3.15 Penalty Case|Little Red Book fined 50,000 yuan for “leaking” consumers’ personal privacy! Retrieved from China Consumer News website: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/rNnynndfbCAlCg4-JktVJQ

- Jiang, M. (2018, March 28). Yanhong Li’s “Privacy for Convenience” is disturbing. Retrieved from People.cn website:

http://opinion.people.com.cn/n1/2018/0328/c1003-29894674.html - Flew, T. (2019). Platforms on Trial. Intermedia, 46(2), 18–23. https://eprints.qut.edu.au/120461/

- Suzor, N. P. (2019). Who Makes the Rules? In Lawless: The Secret Rules That Govern Our Digital Lives. Cambridge University Press.

- Zhou, W., & Cai, X. (2017, December 13). “Live” surveillance videos for everyone to watch, for what? Retrieved from BBC News Chinese website: https://www.bbc.com/zhongwen/trad/chinese-news-42336636

- Purple Hill Technology. (2021, August 16). Behind the black market of webcast: trampled privacy, trapped in the maintenance of rights . Retrieved from myzaker website: https://www.myzaker.com/article/611e63c38e9f0940ca4a0a81

- Yonhap. (2017, December 19). Gov’t passes legislation banning installation of all cameras at bathhouses, restrooms. Retrieved April 8, 2022, from Yonhap News Agency website: https://en.yna.co.kr/view/AEN20171219007400315

- Gan, N., & Culver, D. (2020, April 16). China is fighting the coronavirus with a digital QR code. Here’s how it works. Retrieved from CNN website: https://edition.cnn.com/2020/04/15/asia/china-coronavirus-qr-code-intl-hnk/index.html

- Huang, J. (2020, June 22). China’s virus tracking technology sparks privacy concerns. China’s Virus Tracking Technology Sparks Privacy Concerns. Retrieved from https://www.voanews.com/a/covid-19-pandemic_chinas-virus-tracking-technology-sparks-privacy-concerns/6191538.html

- Xiao, E. (2021, August 20). World. Retrieved April 2, 2022, from WSJ website: https://www.wsj.com/articles/china-passes-one-of-the-worlds-strictest-data-privacy-laws-11629429138