Introduction

Today, with the continuous development of new media, many innovative technologies beyond the old media form have been created, such as algorithms, personalized recommendation services, etc.

These technologies not only help users to obtain more personalized information and services but also help enterprises to carry out more targeted marketing promotions, to obtain more profits. For example, advertising based on personalized targeting is displayed to arouse consumers’ interest more. Therefore, filter bubbles are created based on algorithmic techniques to satisfy user personalization. In other words, personalized services.

There is no longer a need for users to voluntarily switch the channel they want to watch or browse another section of the newspaper, as was the case with traditional media in the past. Personalization services may make you feel comfortable when you’re browsing through shopping sites like Amazon, or when you’re browsing through Instagram or TikTok, and the algorithm seems to have guessed your mind. You may not realize that behind this phenomenon, the products, videos, advertisements, and other consumer goods pushed to you by the algorithm are based on your data and statistics of previous behavior patterns, such as likes, comments, retweets, favorites, and even the length of time you stay on the page to calculate what information you prefer to obtain. Algorithms seem to create a win-win situation for both users and businesses.

However, is personalized customization service applicable to all areas of human life? Or do algorithms that seem to benefit users and companies harm certain areas of human life? The author believes that the filter bubble in social media encourages users’ polarized thinking on political issues, promotes narrow political prejudice to some extent, and undermines democracy.

What is the “filter bubble”?

Internet activist Eli Pariser coined the term “filter bubble”. Filter bubbles are websites or platforms that use algorithms to make assumptions about what users want to see and serve information to users based on that assumption. The algorithm learns relevant information about the user, such as the user’s basic information and the user’s web activity history, such as click behavior, browsing, and searching history. Websites are more inclined to provide more information that matches the user’s past activities and behavior patterns. In this case, filter bubbles lead to less exposure to information outside of the user’s behavioral patterns and personal choices, and less contact with conflicting or different views of information, leading to the user’s intellectual isolation. In other words, as personalization tools and algorithms on various online platforms show users only the news and information they already approve of, it can lead people to ignore other perspectives (Pariser, 2011).

A filter bubble, it is also possible to look at this term in isolation. Filter means that the algorithm helps users filter the information they want more, in other words, the information they prefer to see. A bubble, seemingly transparent, is an enclosed space. The Internet may seem barrier-free, but people of different cultural backgrounds, races, genders, ages, and similar interests gather together to form online communities, people who come together to form online communities based on the same interests are invariably a form of segregation and even exclusion of others who do not share the same characteristics.

Therefore, from the perspective of political participation, the emergence of filter bubbles may be detrimental to the development of democratic politics and the development of the diversity of views, contributing to ideological segregation.

Changes in Access to Political News

With the development of new media, the way of obtaining current political news has been changed, and the filter bubble has also exerted a subtle influence on the users who browse news in this change.

According to the Pew Research Center, approximately 61 percent of millennials get their government and political news from Facebook, which claimed in 2016 that its platform would “building a better news feeds for you”, providing information with characteristics that are “subjective, personal, and unique — and define the spirit we want to achieve.” Surveys show that Facebook reaches 67 percent of U.S. adults, and more than 40 percent of people get their news from the social media platform. Facebook has redefined the consumption of online news, not only by algorithmically controlling users’ newsfeeds but also by making it more likely that people will participate in voting. The personalized news model proposed by Facebook is the embodiment of the filter bubble on Facebook. Based on this algorithm, users will no longer be prioritized to receive news that is not personalized to them, or that contradicts their views. This may have exacerbated users’ news bias, constantly entrenching users’ ingrained ideas and affecting political polarization.

It’s not just social media. About half of Americans use search engines to access news online. 33% of millennials get their political news from Google. Thus, Google’s filtering bubble also has an impact on the information users receive.

Trump’s unexpected victory in 2016

Donald Trump’s successful election as President of the United States in 2016 was an outcome that many did not anticipate. Throughout the course of Trump’s election, the filter bubble continued to demonstrate its ability to manipulate the psyche of its users and polarize groups. Filter bubbles segregate people who hold different views, exacerbating the creation of political polarization. By showing the emergence of filter bubbles on social media during Trump’s 2016 campaign, we can learn about the existence of filter bubbles as well as their negative impact on democracy and their effect on the constant antagonism of citizen ideologies.

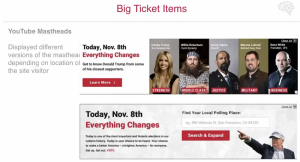

One example of a filter bubble that somewhat influenced the outcome of the election was the revelation that Cambridge Analytica helped Trump win the election by algorithmically pushing different kinds of propaganda ads to different types of voters across multiple social media platforms on Google, Snapchat, Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube. For example, in areas likely to support Trump, voters are presented with images of Trump’s spiritedness and exuberance, and users are reminded to the nearest polling station. But swing voters, according to geographic information, will receive photos of high-profile supporters, including his daughter Ivanka Trump and other celebrities (Fig. 1). This is the embodiment of the filter bubble on the social platform, which is trump’s hidden means of election. However, it is undeniable that the filter bubble has affected voters’ ideas to a certain extent in the above operation and damaged the democratic election to a certain extent.

EiBermawy described his observation that Trump’s social media and website performance was significantly higher than Clinton’s before the election, including the number of followers and post engagement rates. However EiBermawy, as a liberal New Yorker, never showed up on his Facebook news feed or the social media of his liberal New York friends for similar articles close to Trump. Instead, his social media feed was filled with content from Trump competitors like #ImWithHer or #FeelTheBern. This example can be used as a demonstration of the influence of filter bubbles on ordinary Facebook users during the election. We can notice that when the user is inclined to support one side or the other, the filter bubble will only keep pushing the user with information that shares his opinion. The lack of views in favor of the other party is not even visible, which shows that the filter bubble is potentially consolidating the user’s ideology and causing a constant state of bifurcation of people’s views on politics.

Another example is BuzzFeed News’s comparison of comments from a live broadcast of a Trump speech (Fig. 2). BuzzFeed News captured two different Facebook News Feeds of the press conference, Fox News and Fusion, and counted the total number of user reactions to the comments (Fig. 3), and the results were quite different. Fox News showed more pro-Trump comments and Fusion users posted more negative comments and angry emojis (Fig. 4). BuzzFeed News called it a real-time filter bubble. The emergence of this phenomenon once again confirms that the filter bubble divides users with different viewpoints, resulting in users’ political polarization and ideological opposition. People rally around media organizations that fit their beliefs and ignore other media. The Internet once thought to open the world to all possible information and bring people together, now draws people to their community (Newman et al., 2017). Such a stark comparison of results is evidence of both the existence of filter bubbles and their effect on the polarisation of political opinion. Pariser’s view on the polarization of political views due to filter bubbles states that democracy requires citizens to see things from each other’s perspectives, but citizens are increasingly enclosed in their bubbles. Democracy requires citizens to rely on common facts, but the information available to them is parallel but independent content (Andrejevic, 2019).

Fig. 2. BuzzFeed News compared the differences in the real-time filter bubbles of the two news feeds, from https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/lamvo/this-is-what-facebooks-filter-bubble-actually-looks-like

Group effect of filter bubbles

These examples also exemplify to a certain extent the group effect of filter bubbles, which when a group is in a filter bubble, it is easy to lead to the generation of group thinking. Because filtering bubbles keep the group from hearing different voices, individuals in filter bubbles essentially receive only the information they have selected in advance, or worse, a third party gives the information directly to the user, forming a kind of group isolation phenomenon on the Internet (Lessig, 2006). Therefore, under the influence of the filter bubble, it is easy to create groupthink with a single point of view.

The concept of a “social bubble” is the machine learning that occurs when users use an online site, driving the machine to recommend more content to the user, thereby reinforcing existing beliefs (Flew, 2021). Moreover, the conditions that shape individual tastes depend on the underlying social and group forms that enable people to feel a commonality of interest (Andrejevic, 2019). Therefore, people follow the rules of the community, gradually forming personal views and reinforcing beliefs in the same views, constantly consolidating the reinforced, unifying notion of community, which may eventually lead to extreme results.

To conform to the same rules as the community and not to be r excluded from the community, which in turn leads to users choosing to avoid having opposing views to the community, the opposing views are also drowned out in the community discussions. For instance, if you tend to support President Trump, filtering out comments that the bubble supports solidify your trust in Trump, even letting you go against unflattering comments. People are immersed in their filter bubbles, reinforced by the group effect, which eventually leads to political polarization. The filter bubble also explains why Trump’s victory was unexpected, as people who thought Trump would lose existed within their community bubbles and were blind to the fact that Trump also had a large number of supporters in other communities.

As a result, filter bubbles may become a source of polarization and prejudice, which is detrimental to the development of democracy and may widen the gap between those who are informed and those who are not involved in politics (Dubois et al., 2020). It may even contribute to the creation of extreme problems.

Conclusion

How to reduce the impact of filter bubbles on political polarization?

Once we are aware of the existence of filter bubbles, and that they can have such a strong influence on our political thinking and ideology, we can take the initiative to reduce them or break down group barriers and reduce our biases.

From a platform perspective, filtering bubbles cannot disappear completely, and what users can do is perhaps clear their search history or use multiple search engines to participate in news activities. Try to put yourself in an objective and diverse environment. Users can also choose to browse more neutral traditional and mass media. Although more people are turning to Facebook and other social platforms to get news, we can try to listen to more diverse voices. By browsing more diverse news sites and mass media, we can ensure our democratic right to know, cultivate civic awareness through education, avoid ideological confrontation and increasing polarization of political views, and reduce the emergence of extreme ideas and prejudices, which will also contribute to democratic deliberation and maintain the stability of social order.

Reference List

Andrejevic, M. (2019). Automated culture. In Automated Media (pp. 44-72). London: Routledge.

Dubois, E., Minaeian, S., Paquet-Labelle, A., and Beaudry, S. (2020). Who to Trust on Social Media: How Opinion Leaders and Seekers Avoid Disinformation and Echo Chambers. Sage Journals, 6(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305120913993.

ElBermawy, M. (2016). Your Filter Bubble is Destroying Democracy. Retrieved from Wired https://www.wired.com/2016/11/filter-bubble-destroying-democracy/

Flew, T. (2021). Regulating platforms. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

Fs. (n.d.). How Filter Bubbles Distort Reality: Everything You Need to Know. Retrieved from https://fs.blog/filter-bubbles/#:~:text=In%20important%20ways,%20your%20social,at%20what%20level%20you%20operate.

Gibney, E. (2018). The scant science behind Cambridge Analytica’s controversial marketing techniques. Retrieved from Nature https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-018-03880-4

Lessig, L. (2006). Code: And Other Laws of Cyberspace, Version 2.0. New York, Copyrighted material.

Lewis, P., Hilder, P. (2018, March 23). Leaked: Cambridge Analytica’s blueprint for Trump victory. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2018/mar/23/leaked-cambridge-analyticas-blueprint-for-trump-victory

Mitchell, A., Gottfried, J., & Matsa, E. K. (2015). Facebook Top Source for Political News Among Millennials. Retrieved from Pew Research Center https://www.pewresearch.org/journalism/2015/06/01/facebook-top-source-for-political-news-among-millennials/

Mosseri, A. (2016). Building a Better News Feed for You. Retrieved from https://about.fb.com/news/2016/06/building-a-better-news-feed-for-you/

Newman, N., Fletcher, R., Kalogeropoulos, A., Levy, D., Nielsen, K. (2017). Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2017. Retrieved from https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/our-research/digital-news-report-2017.

Pariser, E. (2011). The filter bubble: what the Internet is hiding from you. London: Viking.

Techopedia. (2018). Filter Bubble. Retrieved from https://www.techopedia.com/definition/28556/filter-bubble

Vo, T. L., Warzel, C. (2017). Here’s What Facebook’s Live Video Filter Bubble Looks Like. Retrieved from BuzzFeed News https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/lamvo/this-is-what-facebooks-filter-bubble-actually-looks-like