Introduction

In the digital age, algorithms based on Artificial Intelligence (AI) and machine learning play an important role in many aspects of today’s society; from bank credit scoring to crime risk assessment, more and more private and public sectors have started to use algorithms to process large amount of data or help automate decision-making processes. In the pre-algorithmic era, people make decisions based on legal or social norms. Today, algorithms can weigh up the pros and cons based on multiple data models and make simple or complex decisions for humans. Although the scale and rigour of algorithms have led to unprecedented efficiency gains (Lee, Resnick, & Barton, 2019), some cases have shown that algorithms can also generate or amplify discrimination based on gender, race, or economic status, even though the algorithm developers do not have the intention (Hajian, Bonchi, & Castillo, 2016).

Starting with case studies of Amazon’s recruitment algorithm and the COMPAS crime prediction algorithm, this paper aims to summarise and analyse the reasons for algorithms generating bias and discrimination. After analysing the causes, the paper discusses how to detect bias, and then makes suggestions to address the issue from the developer/operator, legislation and the public perspective, in order to help reduce the discriminatory outcomes produced by algorithms.

Sexism in Amazon’s hiring algorithm

As one of the world’s largest technology companies, Amazon has always been a heavy user of algorithms. Amazon has been using hiring algorithms to review job applicants’ resumes since 2014, in order to help the company find top talents. The algorithm uses AI and machine learning to rate job applicants on a scale from 1 to 5 stars, much like shoppers rating items on Amazon. However, it wasn’t until 2015 that the company realised its hiring algorithms weren’t treating technical position applicants in a gender-neutral way. According to a Reuters report (Dastin, 2018), Amazon engineers trained the algorithm to identify patterns from resumes submitted to Amazon over the last 10 years, and then select new applicants based on these patterns. However, these resumes were predominantly from white males. It was trained to identify keywords instead of skill sets in resumes, and benchmark the data against the company’s predominantly male technical departments to determine the applicant’s rank. As a result, the recruitment algorithm downgraded resumes that contained the word “women” in the text, such as “captain of the women’s debate team”. In addition, the algorithm also downgraded the weight of graduates from two women’s colleges (Dastin, 2018), thus creating a gender bias. After realising that its recruitment algorithm was sexist, Amazon stopped using it for hiring (Vincent, 2018).

According to a 2017 survey by CareerBuilder, approximately 55% of US HR managers believe that AI and machine learning-based hiring algorithms will be part of their job in the next five years (CareerBuilder, 2017). Employers have always wanted to use technology to match talent quickly and efficiently. However, Amazon’s example proves that there is still a lot of work to be done to ensure that this type of recruitment is truly fair for the candidates.

Bias in criminal justice algorithms — the COMPAS case

In May 2016, investigative journalism agency ProPublica claimed that an algorithm used to determine whether a defendant awaiting trial is too dangerous to be released on bail, is biased against black defendants (Angwin et al., 2016). The algorithm, named COMPAS (Correctional Offender Management Profiling for Alternative Sanctions), was developed by Northpointe to help judges make bail and sentencing decisions. The COMPAS algorithm scores defendants based on age, gender, criminal history arrest history, and other factors to assess the defendant’s likelihood of re-offending in the future. According to ProPublica, in general, black defendants are likely to receive higher scores than white defendants, resulting in longer periods of detention while awaiting trial (Angwin et al., 2016). However, Northpointe denies this claim. They claim that the COMPAS algorithm accurately predicts a defendant’s re-offend rate, regardless of the defendant’s race. However, because the overall recidivism rate for black defendants is higher than for white defendants, which leads to black defendants who do not re-offend are predicted to have higher risk than white defendants. Here’s the problem: one scoring system can’t meet two standards of fairness. Although race was not a parameter of the algorithm, the algorithm still produced results unfavourable to black defendants based on the dataset.

Reasons for the bias

There are many reasons for the algorithm to produce discriminatory results, and the deviation may come from any part of the calculation. Based on the two cases mentioned earlier, this paper focuses on two main reasons for bias algorithms: training data deviation and human discrimination.

-

Training data deviation

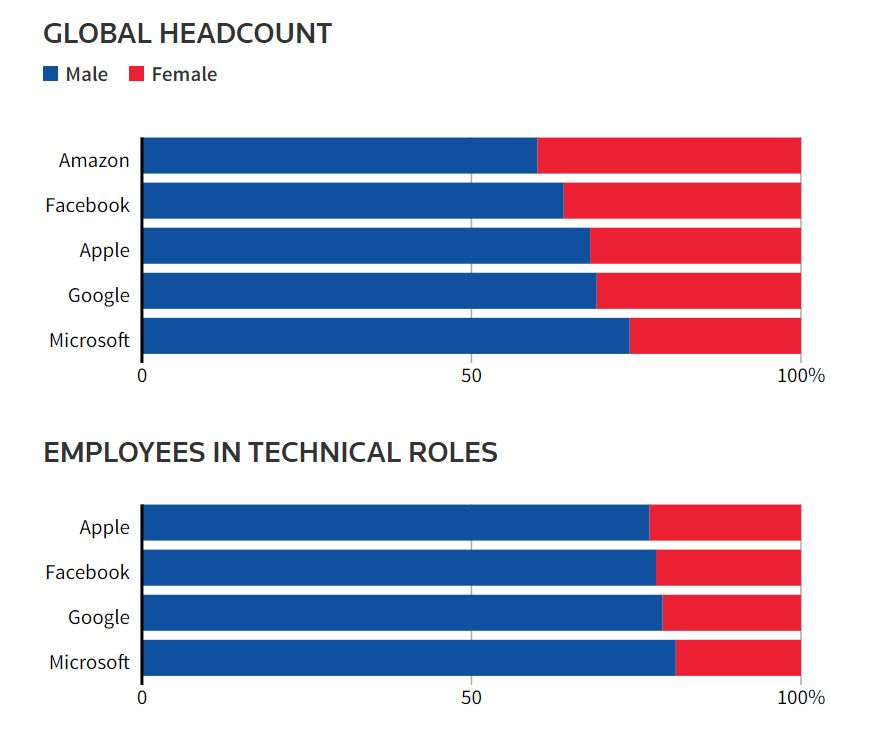

In the case of the Amazon recruitment algorithm and the COMPAS algorithm, a notable commonality is that neither of the developers of the algorithms used race or gender as parameters of the algorithms, but the algorithms still produced sexist or racist results based on the datasets that used for training. Algorithms usually learn through historical data, and any predictive algorithm based on historical data is likely to inherit historical biases (Köchling & Wehner, 2020). If the historical data used to train the algorithm is biased in some ways or does not correctly represent the characteristics of the target population, the results will likely be biased (Ferrer et al., 2021), just as Mayson (2019) stated “Bias in, Bias out”. In the case of Amazon’s hiring algorithm, it learned by heavily referencing resumes from male employees over the past decade and benchmarked men as professional ‘fits’, resulting in penalising female candidates’ resumes. In addition, insufficient, under-representative or over-representative data also contributed to the biased results (Köchling & Wehner, 2020). According to the Reuters report (Dastin, 2018), female employees make up 40% of Amazon’s workforce, while in the technology sector they only make up 23%. Such a gender ratio can also be found in other Silicon Valley tech companies, reflecting the dominance of men in the tech industry. As women are under-represented in the dataset used for training, and male employees are over-represented with too much data, the results favour the larger group (i.e. men), thus producing discriminatory results.

Gender Ratio of Major Technology Companies. Image Source: Screenshot

-

Human discrimination

Prejudices ingrained in societal values against certain groups may be reflected in the dataset and thus will be replicated and amplified by algorithms (Lee, Resnick, & Barton, 2019). In other words, the deeper cause of the bias is not the algorithm, but the discrimination and prejudice in society throughout history. In the case of the COMPAS algorithm, criminal records and arrest records have a significant impact on the prediction of the likelihood of re-offending: to determine who is likely to commit a crime in the future, it is necessary to look at who has committed crimes in the past. If it is because of historical racism, inequalities in policing practices and judicial practices had led to more arrests and incarceration of African Americans compared to white people, then this bias will be reflected in the historical dataset that used to train the algorithm, which will eventually be reflected in the algorithm’s prediction results. The reality is that in most states of the United States there are racial disparities in arrest rates for almost all crime categories, people of colour are more likely to be arrested in general; African Americans are incarcerated at almost five times the rate of whites in the United States (Nellis, 2021). It can be argued that historical human discrimination has largely contributed to bias in the data and outcomes of algorithms. Correcting these biases caused by social issues is more difficult and complex than just fixing technical problems.

Detecting bias

It is not enough to just understand the causes of bias in algorithms; knowing how to detect and prove the existence of bias is equally important. It is important to note that in the bias detection phase, even after correcting deviation in the training data, the results may still be problematic, because identifying a bias requires it to be defined specifically according to the context (Ferrer et al., 2021). Therefore, it cannot be assumed that the results will not be biased simply because the training data is correct. As the case of the COMPAS algorithm shows, the algorithm developer Northpointe claimed that the recidivism rate of black and white defendants who were given the same score was almost equal, so the algorithm’s decision was correct; however, ProPublica was concerned that black defendants who did not re-offend were given the same risk score as those who re-offended, which was unfair to them. The underlying reason for this is that Northpointe and ProPublica have different definitions of bias, and their definitions arise from different perspectives based on the context. The algorithmic bias caused by this divergence is difficult to solve from the technical perspective only. Therefore, in order to mitigate algorithmic discrimination, diversified and multi-angle measures are needed, in order to provide solutions from interdisciplinary perspectives.

Mitigating algorithmic discrimination — future suggestions

-

Algorithm developer/operator Perspective

Algorithms are usually private property of technology companies, so the developers or operators of algorithms have more control over their algorithms than institutions or people that are using them. For developers of algorithms, diversity should be considered at the designing stage of the algorithm, including encouraging diversified technicians to participate in algorithm development, and adding inclusive space for minority groups in the design (Lee, Resnick, & Barton, 2019). Algorithm operators should hire technical personnel and cross-disciplinary experts to regularly check algorithms, and correct data or technical deviations in a timely manner to avoid more serious impacts.

-

Legal protection

Legislators should consider incorporating algorithmic discrimination into the current anti-discrimination legal framework. Although legislation against discrimination exists across the globe, most of them simply contain a list of attributes (e.g. gender, race), and prohibit discrimination based on that (Criado & Such, 2019). With the rapid development of algorithmic technologies, it is necessary to critically reflect on the current legal framework in a digital context, and create a newer legal and ethical framework based on existing laws that can define and describe algorithmic discrimination. This framework needs to be able to clarify the extent to which algorithms or datasets are in violation of anti-discrimination norms.

-

Raising public awareness

As algorithms are increasingly applied to many aspects of life, the public, who are the subject of algorithmic decisions, should have good algorithm literacy. Rather than blindly assume that algorithms are impeccably objective, the public needs to be educated to understand the fundamentals of how algorithms work, how they generate bias and what to do about it when it happens. Public feedback on algorithms can in turn help developers to identify and correct biases, allowing those affected by biased decisions to play an active role in promoting algorithmic fairness.

Conclusion

The use of algorithms to process large amounts of data or to make decisions instead of humans has become a powerful trend in the digital era. However, algorithms may make decisions that are unfair to certain groups for a number of reasons. One of the reasons is that the training data is under-representative or over-representative. But the deeper reason is that historical biases against particular groups have reflected in the dataset and algorithms. In order to mitigate algorithmic bias, it is not enough to just understand the causes of biases, algorithms also need to be put into contexts to detect bias. Even if the data used to train the algorithm is sufficient and comprehensive, and the predictions are accurate, it may still produce discriminatory results in different contexts. Digital bias is not just a technical problem, but a social problem. Promoting algorithmic fairness requires a concerted effort by algorithm developers, operators, legislators and the public, in order to find a balance point between accuracy and fairness, and minimize the impact of bias.

Reference List:

Angwin, J., Larson, J., Mattu, S., & Kirchner, L. (2016). Machine bias. In Ethics of Data and Analytics (pp. 254-264). Auerbach Publications.

CareerBuilder. (2017). More Than Half of HR Managers Say Artificial Intelligence Will Become a Regular Part of HR in Next 5 Years. Retrieved May 18, 2017, from https://press.careerbuilder.com/2017-05-18-More-Than-Half-of-HR-Managers-Say-Artificial-Intelligence-Will-Become-a-Regular-Part-of-HR-in-Next-5-Years

Criado, N., & Such, J. M. (2019). Digital Discrimination. In N. Criado & J. M. Such, Algorithmic Regulation (pp. 82–97). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198838494.003.0004

Dastin, J. (2018, October 11). Amazon scraps secret AI recruiting tool that showed bias against women. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-amazon-com-jobs-automation-insight-idUSKCN1MK08G

Ferrer, X., Nuenen, T. van, Such, J. M., Cote, M., & Criado, N. (2021). Bias and Discrimination in AI: A Cross-Disciplinary Perspective. IEEE Technology & Society Magazine, 40(2), 72–80. https://doi.org/10.1109/MTS.2021.3056293

(pp. 254-264). Auerbach Publications.

Gawronski, Q. (2019). Racial bias found in widely used health care algorithm. Retrieved from the NBC News website: https://www.nbcnews.com/news/nbcblk/racial-bias-found-widely-used-health-care-algorithm-n1076436

Hajian, S., Bonchi, F., & Castillo, C. (2016). Algorithmic Bias: From Discrimination Discovery to Fairness-aware Data Mining. Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, 2125–2126. https://doi.org/10.1145/2939672.2945386

Köchling, A., & Wehner, M. C. (2020). Discriminated by an algorithm: a systematic review of discrimination and fairness by algorithmic decision-making in the context of HR recruitment and HR development. Business Research (Göttingen), 13(3), 795–848. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40685-020-00134-w

Lee, N. T., Resnick, P., & Barton, G. (2019). Algorithmic bias detection and mitigation: Best practices and policies to reduce consumer harms. Brookings Institute: Washington, DC, USA.

Mayson, S. G. (2019). Bias in, bias out. The Yale Law Journal, 128(8), 2218–2300.

Nellis, A. (2021, October 13). The Color of Justice: Racial and Ethnic Disparity in State Prisons. Retrieved from https://www.sentencingproject.org/publications/color-of-justice-racial-and-ethnic-disparity-in-state-prisons/

Vincent, J. (2018, October 10). Amazon reportedly scraps internal AI recruiting tool that was biased against women. Retrieved from https://www.theverge.com/2018/10/10/17958784/ai-recruiting-tool-bias-amazon-report