Introduction

With the rapid spread of social media platforms and online communities, these platforms, which can be anonymous or under pseudonyms, have become a venue for various forms of electronic trolling, malicious vilification, and the publication of harmful content. While users enjoy a high degree of information convenience, they also bear the negative consequences of misinformation. This polarized result eventually gave rise to platform content moderation and turned it from an auxiliary job into a highly professional and independent new industry. This is one of the core jobs of the Internet, and the quality control of the platform is thus grasped. Major platforms such as Google and Facebook have many information reviewers monitoring the quality of the entire platform, and these review teams play a vital role in the information orientation of the platform. However, as platform users’ amount of user-generated content grows, it is no longer sufficient to use traditional human-led auditing methods at the speed and scale necessary to identify and remove harmful content. China Internet Network Information Centre (CNNIC) released the latest Statistical Report on the Development of the Internet in China, which showed that the number of Chinese Internet users reached 1 billion, and mobile phone users even reached 800 million. It is a foregone conclusion that artificial intelligence has primarily replaced workers as the main protagonists of this work. Artificial intelligence technology has made censorship much easier, but determining whether the content is harmful is not as easy as one might think. While certain content can be easily identified through analysis, other content requires an understanding of its surroundings. This is a constant challenge for automated systems and humans simply because it requires a comprehensive understanding of cultural, social, political, and historical factors.

Back in the 2019 Cambridge Consultant’s report, FCOM recommended “Use of AI in online content moderation”. This blog will discuss the new challenges that automated AI-based systems face when identifying content and why it is essential to continuously improve the technology to always screen platform content and insist on a high-quality platform content presentation, where continuous screening refers to the fact that platform content moderation is not a one-off exercise, but is divided into long periods of constant attention similar to pre-moderation and reactive-moderation, as socially hot and sensitive topics are not endless, are dynamic and subject to change with content orientation. Besides, it is worth examining the fact that the boundaries of content censorship cannot be precisely grasped and that the process involves many complex relationships, including national regulations, the positioning of platforms, and the social acceptability of content in different cultures, so I will also discuss the chain of relationships between the government, the platform, and the users collectively as the content orientation changes with the development of the Internet.

Challenges

AI has been a hot topic in recent years, and its technology and algorithms have been widely used in people’s everyday lives. As mentioned earlier, the online world is a mixed bag of information of all kinds, and intelligent filtering and blocking functions have become an immediate need for content platforms. However, there are two very different views on the results of this. The most illustrative example is sexual content in pornography. A Facebook content reviewer mentioned before leaving that they were required to continuously watch indecent images of violence, pornography, and abuse during their working hours but that the company did not have a position to provide them with psychological support, the results of which are unknown, as Roberts, Sarah T. (2022), and that content that has been Artificially optimized content can easily be sold or distributed profitably. From this perspective, AI is indeed a better option. In 2018, China’s Alibaba Group presented the results of their AI ‘pornography’ research, with algorithm experts claiming that their AI ‘pornography’ model can already thoroughly vet images, voice, and video. The algorithm experts said that their AI “pornography” model can already review pictures, voices, and videos in their entirety and can even recognize foreign languages such as English, Japanese and Russian, making it hundreds of times more efficient than manual review. This may seem to have taken the job to a higher level. Still, the most challenging part of reviewing content is the issue of standards, the boundary mentioned above. The definition of ‘offending standards’ for much content is vague, with a new standard being updated when a new example is encountered.

Even though the current stage of AI technology has largely achieved accurate auditing, this has also given rise to another problem. AI will screen out or directly delete content that has obvious issues, but it may also identify misunderstandings, such as the keyword ‘sex’, but the presence of this word in certain statements does not mean that its content is against the rules. Removing content that is not generally considered harmful can also lead to reputational damage and undermine users’ freedom of expression, often taken much more seriously than one might think. Furthermore, the iterations of the times have made it difficult for AI to identify platform content. This is the main reason why the platform is still regulated by the “manual + AI” form of content regulation at this stage, with the AI pre-moderation of the content posted by users; when the content is reviewed after publication, automated processes or other users flag it as potentially harmful, or content that has been removed but has been appealed, reactive-moderation is required. But even then, there is still content that is difficult to detect both manually and by artificial intelligence. Content on the web is delivered in a wide variety of formats. Video content is a representative example: it requires that image analysis across multiple frames combined with audio commentary. This is particularly the case with falsified media, where one person in an existing video or image is replaced with the likeness, which often spreads at a multiplied rate, seriously infringing on the reputation and likeness rights and causing great harm. This is currently the most prominent blind spot in platform content review.

Contradictions

Contradictions exist in almost everything, and here we will focus on conflict points in the government (regulation), the platform, and the users collectively (society). It is essential to be clear that the target of government regulation is, to a greater extent, a constraint on platforms, as the number of users is too large for the enactment of laws and decrees to be directly targeted at individuals; whereas the target of platforms is the collective of users, but each platform has its niche and profitability, as platforms are, in essence, run by people; users (society) are only there to get the information they want on the platform, and they Mostly are d unaware (or do not care) about the implications of government regulation of content. While governments claim that legislation is needed to regulate platforms to protect the rights and privacy of users (and indeed there are measures in place to do so), political factors must be mentioned here. The complexity of censoring content on platforms lies in the fact that there are complex conflicts between states that are not limited to interests, and in addition to the reasons mentioned above, governments inevitably need to use the power of platforms as a political tool to achieve certain ends. We will not expand on this here.

The regulation and review of content on digital platforms need to start with national legislation, and platforms in each country do not exist independently. In 2017, Germany passed an online law enforcement law; in 2019, the European Parliament supported a proposal for a restriction on terrorist content that would require the removal of terrorist material within one hour of notification; and China has been sovereign in its regulation of the Internet. In contrast, the US is stuck with a model of platform regulation designed in the 1990s. And when countries are not uniform about the harmful content that appears on platforms, the toxic material that is legitimized by some countries can have an extraordinarily negative impact on society; hate speech on platforms can lead to hate crimes, and terrorist groups can use platforms to begin acts of terror, such as the beheading videos posted by isis, which spread quickly and widely and caused no small amount of panic around the world.

For platforms, the task of accepting content regulation and the benefits of keeping the platform essentially operational exist simultaneously. In the previous section, the pros and cons of AI review of platform content are not absolute, and it cannot be ruled out that some platforms choose to leave content that should have been removed but failed to be identified to benefit from it. However, these situations are not common on those big platforms, such as Facebook, Twitter, etc.; more often on some small websites (especially those platforms that profit from the way users top up), most of the content posted is not directly searchable by users to obtain. The operation mode of these platforms changes their IP addresses frequently to avoid the government’s pursuit and users’ appeal, which is tricky for AI to identify and challenge non-specialists to track.

In addition, users are the biggest variable factor in platform content review. A group of user populations, including human rights law experts, argue that content moderation is a huge threat to free expression, with one argument being that the problems posed by active identification and automatic removal of user-generated content go beyond the issues of ‘accuracy’ and over-scoping, and that these problems will not be solved by better artificial intelligence.

The cooperation and constraints of the government (regulation), the platform (content) and the user (society) go hand in hand. Firstly, the government uses legislation to regulate the content published on the platforms while using the platforms as a tool to set political and public opinion orientations, thus controlling the information users receive on the platforms; secondly, the platforms use unclear legislation to create eye-catching traffic content to attract more users and therefore gain more significant profit while performing the basic task of content review; users are almost oblivious to the regulation of the content on the platforms, as they are unable to judge the legitimacy of platform content.

Conclusion

In conclusion, there is no doubt that the influence of platform content auditing in the digital age is pervasive. It can affect the stability or turmoil of the whole society. It also bears the responsibility and obligation to educate society. Digital platforms have become one of the mainstays of people’s lives, and in the process of constantly improving the platform content audit mechanism, the government should continuously update the legislative provisions and platforms should pay more attention to the intelligence of the AI process in order to find the best way to ensure that platform content and information dissemination is healthy and that users are not victimized by harmful content in the process of experiencing and searching for information. Content auditing practices on digital platforms should be regulated in a correct way to contribute positively to the global dialogue. So far, there is still a long way to achieve this goal.

References

Tim, W. (2019). Ofcom: Use of AI in online content moderation. Retrieved July 18, 2019 from: https://www.cambridgeconsultants.com/insights/whitepaper/ofcom-use-ai-online-content-moderation

CNNCC. (2022). The 49th Statistical Report on the Development Status of the Internet in China. Retrieved February 25, 2022 from: http://www.cnnic.cn/hlwfzyj/hlwxzbg/hlwtjbg/202202/t20220225_71727.htm

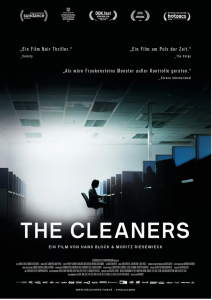

Block, H. (2018). Im Schatten der Netzwelt. Retrieved January 19, 2018. Documentary.

Roberts, Sarah T. (2019). Behind the Screen: Content Moderation in the Shadows of Social media, pp. 33-72.

Jianxun, S. (2021). Ali Artificial Intelligence Products. Retrieved December 11, 2021 from: http://www.chinaai.com/baike/10494.html

Tanker. (2021). ‘AI is faster than humans, but pornographers say it’s unreliable?’ Retrieved June 1, 2021 from: https://www.tmtpost.com/5359480.html

MacCarthy, M. (2019). A Consumer Protection Approach to Platform Content Moderation. Retrieved June 22, 2019 from: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3408459

Yuichiro, Chino. ‘Wake Up Robot’. Getty Creative, from: https://www.vcg.com/creative/1275030519

Oliver, Burston. ‘AI face swap’. Ikon Images, from: https://www.vcg.com/creative/1284638206