Introduction

The digital media environment is far faster, more pervasive, and far more controlled than the human ability to process information, and automation is one of the key tools for centralizing and controlling communications globally and is widely applied by tech giants such as Google Search and Facebook Custom Information Systems. (Andrejevic, 2019, p.26). The emergence of algorithms can also be seen as a very important element in the automated culture, adapting the user experience better to its preferences. Algorithms also shape the governance mechanisms of content service production and consumer preferences in the Internet environment by influencing individual producers and user experiences and categorizing information (Just and Latzer, 2017). From the positive perspective of algorithms, they facilitate the construction of personalized services for mass media, classifying groups of participants in the Internet environment (e.g., ‘filter bubble’). However, some opponents argue that crises in such an automated culture also led to numerous endangered individuals being more tightly controlled, such as the echo chamber situation and information cocoons. This opinion polarisation allows users to access relevant information only by confirming their own opinions, increasing the potential for negative information about social culture. In this article, I will illustrate the disadvantages of automation in the Internet environment, i.e., how the echo chamber situation is created. Using case studies reveals how such a crisis can affect users’ emotions and their own opinions and offer some suggestions to avoid being trapped in the information cocoon of the Internet.

Overview

What is the filter bubble?

Before I present you with the echo chamber effect, I would like to briefly demonstrate how the filter bubble works. The filter bubble is designed to give preference to like-minded users, and it assesses the balance of communication between different groups (Bruns, 2019). In a nutshell, it’s a personalized service – it filters the messages you can see according to your preferences. For instance, Jesse Pearson (2014) compared her two friends’ results on Google for information about Egypt and found that one was for news and the other was for pictures of tourist attractions (graphic 1).

Graphic 1. Screenshot from WordPress by Jesse Pearson. (2014). Retrieved from: https://jessepearsondtc475.wordpress.com/2014/02/03/blog-post-3-my-filter-bubble/

This also means that Google prioritises the pages that the algorithm feels users need more based on their browsing history and address. Such personalisation techniques help enterprises improve their efficiency in processing information about users and target their requirements more precisely (Brent, Steven, and Peter, 2020). Nonetheless, this recommendation system, which constantly refers you to popular and interesting posts, can also be considered a major drawback – in effect narrowing your horizons and making you stubborn and unaware of yourself in the Internet environment.

How does the ‘echo chamber’ emerge?

Personal preference is the underlying cause, and personal choice is the most significant motivating factor in the development of the echo chamber effect. Bruns (2019) notes that the fundamental difference between the filter bubble and echo chamber is that the former is concerned with communicating with similar participants, while the latter focuses on connection. Typically, the two communicative and connective structures are blurred and very easily overlap. In this way, the echo chamber situation can very easily develop when users are only willing to stay in a preferred internet environment to access information (e.g., social media platforms – Facebook) and ignore voices from other domains (e.g., traditional media – newspapers, television, and magazine).

Case Study

If you are still confused about the echo chamber effect so far, I will take you into a case study and combine it with theoretical knowledge and data analysis to explore how such an environment affects the user.

The contradictions and extremism of the #metoo campaign

I am sure you have seen such challenges in your social media browsing, or perhaps you are already a participant in this campaign. During a period of heightened mainstream media attention, portraying #metoo as a positive and clear social media movement for women provided an important opportunity for women’s voices to be heard. Initially, it was a campaign against sexual abuse and harassment. As more participants joined, various voices expanded within the social media movement, and contributors began to fight for gender equality and justice for women. On Instagram, this campaign has reached over three million posts (and the number is still growing; graphic 2).

Graphic 2. Screenshot from Instagram. #metoo. 2022. https://www.instagram.com/explore/tags/metoo/

However, the emergence of several radical participants has complicated this movement. This expanded like a butterfly effect, completely altering the original purpose of #metoo for protesting sexual harassment and focusing more on separating males from females (Maricourt and Burrell, 2020). These radical groups seem to be linked to digital feminism and have spawned a substantial amount of hate speech attacking men. As such voices continue to overlap on Twitter, many viewers on social media will see these radical statements repeatedly until they become homogenized with this perspective (Dempsey, 2020). This has led to a tendency for users who were otherwise ‘silent’ about this campaign to start taking the opposite side of the male spectrum. According to Terry Flew (2021, p.92), he mentioned that the hallmark of hate speech is to inflame the emotions of bystanders, causing them to lose their original qualities. Such behaviour is associated with the ‘petri dish of the echo chamber and breeds the spread of uncivilised speech. This is because, firstly, it creates segregation – extremists are separated from men in #metoo. Secondly, the views are polarised, and social media platforms will constantly push and spread such views, cementing their position in the minds of users. In addition to this, the homogenisation of views is also considered a very important element, with negative content coming from a single producer, and when familiar people spread it, users who read it will reinforce the credibility of such views. According to Bouvier’s research (2022) extremism in #metoo was found to be adept at using the word ‘we‘, which better unites women and creates a sense of common purpose, while sharing memes and content to mock and attack males (Figure 3). One tweet, for example:

“#menaretrash is my preferred hashtag. Toxic men are filling the world and we should be working to recycle them. #metoo”

Graphic 3. Via Twitter: @chuuzus

Graphic 3. Via Twitter: @chuuzus

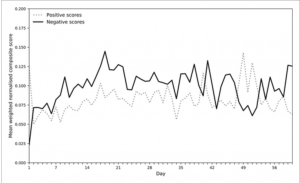

In addition to this, negative information is simultaneously coming from user groups who are opposed to this campaign, creating an increasingly hostile sentiment. When you’re in the movement and don’t want to be a militant feminist. “Congratulations!” You have possibly just fallen into another echo chamber full of negative sentiments attacking #metoo! In such an environment, opponents attack groups that are speaking out for women by using obscene and dirty language. It was purely abusive. According to Lindgren’s (2019) survey of #metoo tweets, the results clearly show that the impact of negative information and emotions is higher overall than positive feedback, and there is an overall increasing trend of negative emotions (Graphic 4).

Graphic 4. Lindgren, S. (2019). #metoo’s daily mood score on Twitter.

Graphic 4. Lindgren, S. (2019). #metoo’s daily mood score on Twitter.

He also identified some examples of negative sentiment about radicals who overreacted in their criticism of #metoo, for instance:

“#MeToo is the dumbest shit ever. Hit me bitch.”

It is the fact that the majority of users in this environment only see relevant and offensive views consistently, which they perceive to be mainstream, that makes the overall trend of similar negative messages to be on the rise. Besides this, the groups abusing #metoo and the extremism of #metoo do not intersect with each other, which makes them more polarised with each other. All this negative information and negativity in both ‘echo chambers’ are affecting the users who see it, even if they have no intention of joining this campaign. When echo chambers emerged, the Internet environment amid them generates massive fake information and hate speech that threaten users’ psychological health (Garrett, 2017). The #metoo campaign is no exception, and there are some fabricated lies in it, with some females masquerading as victims to gain traffic and profit from it. Men may therefore be wrongly accused and thus lose their jobs, which can exacerbate the development of antagonism. If #metoo continues to be misused and the negative messages continue to increase, this could provide plausible deniability for men who are legitimately accused of sexual harassment originally. More disturbingly, this could make it more difficult for women to fight for opportunities in what is already a male-dominated work environment.

Evaluation

How to avoid/break out of the echo chamber?

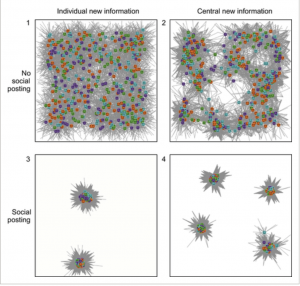

For individuals, this is challenging. Especially when you review content with a biased vision that varies from your point of view, it is frequently to get complacent. It is possible that you are in the situation, but you are not conscious of it. However, it is important to escape the echo chamber effect because it causes you to become parochial and stubborn in your thinking. Also, it may affect your emotions and make your mood polariton. As for solutions, the diversity of individual ideologies is a crucial element. Geschke, Lorenz and Holtz (2019) used algebraic modelling to label user information on social media, comparing the distribution of groups of users with and without social posts. The results show that user information with posts are clustered and forms multiple groups (Graphic 5).

Graphic 5. Geschke, Lorenz and Holtz. (2019).

Graphic 5. Geschke, Lorenz and Holtz. (2019).

It also reveals that to escape the echo chamber, you need to have the habit of observing multiple news sources and analysing the views of others objectively and dialectically on social media platforms. The spread of negative information is a very important feature of the echo chamber. Try to find various voices and viewpoints and make sure that your emotions are not affected by negative posts. In addition, frequently shifting your preferences in a digital media environment makes it difficult for automated tools such as algorithms to clearly pinpoint your characteristics. For instance, you can adjust the priority of your Facebook browsing page by pulling down the ‘News Feed’ from the top right on the screen so that your web information is diverse. Furthermore, communicate with users from different organisations to avoid yourself hearing or receiving only one ‘voice’. From the perspective of digital media platforms, improvements to the feeding and recommendation algorithms have also been a highly effective instrument for breaking the echo chamber deadlock. Platforms should regularly promote content that is disinterested to users (except for advertisements) or even reduce the weight of personal preferences in the recommendation algorithm. Moreover, Internet governance tools for various platforms also need to be strengthened. It is due to the proliferation of fake news and hate speech in echo chambers that these have the characteristics of claptrap. Hence the online environment of social media platforms does have an inescapable responsibility in filtering these negative sentiments and statements.

Conclusion

To sum up, allowing users to make more reasonable judgements about others’ views considering their own limitations and biases is regarded as the fundamental solution to getting rid of the echo chamber. Through the case study, we were able to explore how an ‘echo chamber’ emerged and grew in the social platform environment, while influencing our moods and perceptions, and even our workplace. Instead of using news topics as case studies (e.g., politics and vaccines) for this article, I used the more user-relevant social media challenge #metoo for my analysis. This is because such a scenario is more acceptable to the reader, and you can also think dialectically about the arguments I have presented (no political correctness here). However, it is undeniable that such a polarised environment makes this campaign highly sophisticated and at the border of uncivilisation. This leads us to wonder what kind of groups gain the benefits in such social movements when they generate radical information? Is it related to the satisfaction of the political right? Briefly, it is only the broader knowledge we absorb that makes us appear more tolerant and less liable to be influenced by the negativity of the digital media environment and fall into the echo chamber within it.

References

Andrejevic, M. (2019). Chapter 2: The Bias of Automation. Automated Media (1st ed.). pp.26. Routledge. https://doi-org.ezproxy.library.sydney.edu.au/10.4324/9780429242595

Bouvier, G. (2022). From “echo chambers” to “chaos chambers”: discursive coherence and contradiction in the #MeToo Twitter feed. Critical Discourse Studies, 19(2), 179–195. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405904.2020.1822898

Brent Kitchens, Steven L Johnson, & Peter Gray. (2020). Understanding Echo Chambers and Filter Bubbles: The Impact of Social Media on Diversification and Partisan Shifts in News Consumption. MIS Quarterly, 44(4), 1619–. https://doi.org/10.25300/MISQ/2020/16371

Bruns, A. (2019). Filter bubble. Internet Policy Review, 8(4). https://doi.org/10.14763/2019.4.1426

Dempsey Willis, R. A. (2020). Habermasian utopia or Sunstein’s echo chamber? The “dark side” of hashtag hijacking and feminist activism. Legal Studies (Society of Legal Scholars), 40(3), 507–526. https://doi.org/10.1017/lst.2020.16

Flew, T. (2021). Chapter 3: Hate Speech and Online Abuse. Regulating platforms. Pp. 91-93. Cambridge, UK;: Polity Press.

Garrett, R. K. (2017). The “Echo Chamber” Distraction: Disinformation Campaigns are the Problem, Not Audience Fragmentation. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 6(4), 370–376. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jarmac.2017.09.011

Geschke, D., Lorenz, J., & Holtz, P. (2019). The triple‐filter bubble: Using agent‐based modelling to test a meta‐theoretical framework for the emergence of filter bubbles and echo chambers. British Journal of Social Psychology, 58(1), 129–149. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12286

Just, N., & Latzer, M. (2017). Governance by algorithms: reality construction by algorithmic selection on the Internet. Media, Culture & Society, 39(2), 238–258. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443716643157

Lindgren, S. (2019). Movement Mobilization in the Age of Hashtag Activism: Examining the Challenge of Noise, Hate, and Disengagement in the #MeToo Campaign. Policy and Internet, 11(4), 418–438. https://doi.org/10.1002/poi3.212

Maricourt, C. de, & Burrell, S. R. (2022). MeToo or #MenToo? Expressions of Backlash and Masculinity Politics in the #MeToo Era. The Journal of Men’s Studies, 30(1), 49–69. https://doi.org/10.1177/10608265211035794