Do you have your own social media accounts? Do they create a digital space that works best for you? If the answer is yes, you are experiencing information isolation by Filter Bubble.

This blog will introduce Filter Bubble, the operation of the algorithm, and personalization to explain how the polarization problem of Filter Bubble comes into being. And propose solutions to this problem, including platform behaviors (Burst Your Bubble & Outside Your Bubble) and user behaviors. To further verify the solution of user behavior, Matakos et al. The polarization index model is used to analyze the degree of polarization caused by different user behaviors. Finally, suggestions for the implementation of user behavior solutions are put forward to reduce polarization by changing user behavior through education and motivation.

Filter Bubbles & Algorithms model

When you enter the Internet, you are already drowning in the sea, because you are faced with millions of pieces of information. The experience of the information world makes people realize the limitations of human beings in the face of cultural production (Andrejevic, 2019, p.44). To prevent you from being swamped by thousands of digital messages, the Filter Bubble uses algorithms to help you filter out the messages you most want to see for you to receive. The term ‘Filter bubble’ was introduced and promoted by American technology entrepreneur and activist Eli Pariser in his 2011 book Filter Bubble: What the Internet Hides From You(Bruns, 2019, p.2)

Pariser (2015) proposed “in effect each search engine user exists in a filter bubble – a ‘personalized universe of information'” (as cited in Bruns, 2019, p.2).

Geschke et al. (2018, P30) defined ‘filter bubble’ as the individual results of different processes such as information search, user selection and memory (history record). The individual result is that different users receive only what is right for them from the information world, and these options are tailored to the individual’s pre-existing attitudes on the Internet.

Just & Latzer (2016, pp.241-242) provides an Input – throughput – output model of Algorithmic selection on the Internet. This model clearly explains the operation process of “Filter Bubble”.

As shown in Figure 1 (Just & Latzer, 2016, p.241), the basic model of this algorithm is input base database (DS1), throughput calculation data set (DS2), and output data (DS3). When user requests and user characteristics are entered into the Internet, the algorithm starts to operate on throughput and convert it into output data, such as information, music, movies, rankings, and recommendations. The output data is input again as a user feedback loop to generate user characteristics, which is a continuous iterative process.

Since 2005, algorithms have become increasingly efficient, largely increasing the amount of data available for processing as a result of significant improvements in computing power and speed (Flew, 2021, p.79).

Personalized and result

More and more people are enjoying the convenience of filtering bubbles, such as personalized accounts, personalized recommendations, and personalized search.

Some users rely on personalized services, and they often don’t want their personalized accounts to be contaminated.

For example, Laura, a 26-year-old Netflix user, said she did not want to use the same account as her sister because she and her sister have completely different viewing tastes (Siles, Espinoza-Rojas, Naranjo & Tristan, 2019, p. 505).

“She saw some SOAP operas and some things that I thought were embarrassing when they appeared on my profile and it made I was Angry Because “(Siles, Espinoza-Rojas, Naranjo & Tristan, 2019, p. 505)

The concept of personalization can be traced even further back to Negroponte’s concept of the “Daily Me” in his 1995 book Being Digital (Zuiderveen Borgesius et al., 2016, pp.2-3). Daily Me is a personalized newspaper printed exclusively for each individual. Nowadays, media content has been further personalized.

Personalization is the result of algorithms through big data and part of autonomous learning (Just & Latzer, 2016, p.247). Big data collection includes active data such as user feedback, as well as passive data, based on location, clickstream or social connections. The latter is generated based on users’ personal characteristics and user behaviors (Just & Latzer, 2016, p.248). However, Andrejevic (2019, p.45) suggests that such algorithm-based content challenges the civic character of democratic autonomy.

Based on the input-combinatory-output model of Algorithmic selection on the Internet, we can find that content received by users is always circulating in a framework. As a result, the diversity of users’ access to media content is limited by personalized content and services, and has a negative impact on democratic discourse, democratic thought and the healthy public sphere (Zuiderveen Borgesius et al., 2016, p.2). Influenced by the algorithm, people can only access information that agrees with their own views, or communicate with people with similar ideas (Just & Latzer, 2016, P249). Bruns (2019, p.2) supports the idea that the public in all spheres, such as politicians, journalists, activists, and other social groups, are accused of living in a filter bubble, unable to see the concerns of others.

Filter Bubbles is reinforcing the polarization of opinion

Flew (2021, p.81) presents 5 challenges to the way that algorithms and big data shape personal and social outcomes. One of the challenges is that the machine learning that online sites rely on reinforces the people and content of existing beliefs, and away from the people and content other than beliefs.

It turns out that it’s human nature to like to connect with like-minded people. Users created echo-chambers and filter bubbles for themselves in order to reinforce their existing views (Matakos et al., 2017, p1481).

Once thought to bring people together and open up all possible information to the world, the Internet is now pulling people into their own corners (Newman et al. 2017, as cited in Andrejevic, 2019, p.51).

The individuation of information flow has had a significant impact on People’s Daily life and social political culture (Geschke et al., 2018, p.29). On the one hand, filter bubbles in social media (e.g., Twitter, Facebook, TikTok, YouTube, etc.) increase user engagement while limiting exposure to different viewpoints and even contributing to polarisation with friends, family, and colleagues (Hampson, 2021). The polarization between Twitter and Facebook social media platforms is evident as shown in Figure 3.

On the other hand, many countries are experiencing severe political polarization and fragmentation, for example, the polarizing campaign of Donald Trump (Geschke et al., 2018, pp29-30). Surveys by the Pew Research Center (2014, As Cited in Andrejevic, 2019, p.51) have found that the degree of political polarization in the United States has skyrocketed over the past two decades.

How to improve polarization?

- Passive changes – improved by the platform

In the face of the constant doubts of the society on the filter bubble, the platform should take some relevant measures to reduce the isolation of the filter bubble to users.

(1) (1) Rethink how algorithms work to make filter bubbles more transparent. Fundamentally solve the problem of excessive personalization, so as to achieve a more balanced output information. But considering that the platform algorithm is generated based on the purpose of profit, it seems difficult for the platform to re-change the algorithm in a short period of time.

(2) On the basis of not changing the original algorithm, provide a brand new section that is not affected by the filter bubble for people to choose. This method seems to be more popular among different platforms, such as The Guardian launched a new section “Burst your bubble” (Figure 4), Buzz Feed News launched the “Outside Your Bubble” page (Figure 5).

- Active change – improvement by the individual

While platforms are addressing the phenomenon of information personalization, polarization will not diminish if people continue to click, search or leave footprints on a single fixed piece of information. For example, a user enters the Burst your bubble section of The Guardian, but ignores the diverse information in the section.

We must proactively make changes, such as searching, receiving, publishing, and discussing broader information on the Internet and social media. A broader perspective of content may improve fragmentation and polarization (Andrejevic, 2019, p51)

The polarization index model

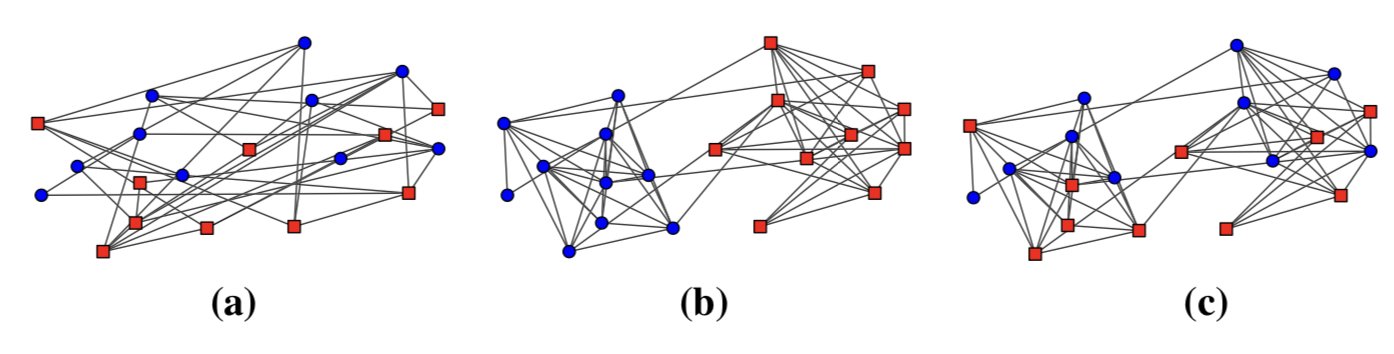

Matakos et al. (2017, p.1486) quantified polarization in the Internet by means of a “polarization index”. As shown in Figure 6, three icons of different polarization indices show polarization in different contexts in the Internet, where each node represents a point of view.

a) Random graph refers to a randomly created network background. There is no community structure in this context, and the polarization index is very low, only 0.03 (Matakos et al. 2017, p. 1486). Positive opinion nodes and negative opinion nodes are equal, 10 red nodes and 10 blue nodes Color nodes are connected to each other.

(b) The Echo chamber graph is a typical echo chamber environment influenced by filter bubbles. In this environment, the polarization index reaches a maximum of 0.30, nodes with positive views communicate with each other, and nodes with negative views communicate with each other (Matakos et al. 2017, p. 1486). The blue community on the left and the red community on the right are formed.

(c) Community structure with random opinion assignment is a situation where opinions are randomly assigned in an environment based on an existing community structure. Since the distribution of opinions in both communities is uniform, the polarization index is not high at 0.03 (Matakos et al. 2017, p. 1486).

The point of Andrejevic can be proved to be feasible through three quantitative plots of the “polarization index”. Users must approach information with a broader perspective. For example, the situation described by the last polarization index icon is ideal. We can find and join our own biased communities on the Internet, but this does not mean closing and self-isolating. We can still keep in touch with people, opinions and information from other communities. If each individual user can achieve broad participation, then opinion polarization will be greatly reduced.

Suggestions

To further solve the polarization problem, Matakos et al. (2017,p.1486) concluded that a broad user perspective can be achieved through educational input and incentives. Make people aware of and learn to engage with different points of view on the Internet and social media. Encourage people to remain neutral when expressing their opinions in the digital public sphere. However, achieving this outcome will be difficult.

“This is an excellent and costly process that may span a generation to yield results.” (Matakos et al.2017,p.1481).

Conclusion

Today, people rely too much on filter bubbles, leading to a sharp rise in social polarization. Polarization is not only achieved by the platform through algorithms and personalization, Echo Chamber is built by us. Every look we make on the Internet, every like and comment we make on social media provides the foundation for building Echo Chamber. So the best way to reduce polarization is to stop polarization from the users themselves. Although the platform should also be reshaped and improved in terms of technology and algorithm, users will still return to the Echo Chamber established by themselves if the reception habits of individuals do not change.

Reference

Andrejevic, M. (2019). Automated Culture. In Automated Media(1st ed., pp. 44-72). Routledge. https://doi-org.ezproxy.library.sydney.edu.au/10.4324/9780429242595

Bruns, A. (2019). Filter bubble. Internet Policy Review, 8(4). https://doi.org/10.14763/2019.4.1426

Buzz Feed News. (2022). Buzz Feed News’s Outside Your Bubble page [Image]. Retrieved 8 April 2022, from https://www.buzzfeednews.com/collection/outsideyourbubble.

Flew, T. (2021). Regulating Platforms. Cambridge: Polity.

Geschke, D., Lorenz, J., & Holtz, P. (2018). The triple-filter bubble: Using agent-based modelling to test a meta-theoretical framework for the emergence of filter bubbles and echo chambers. British Journal Of Social Psychology, 58(1), 129-149. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12286

Haim, M., Graefe, A., & Brosius, H. (2017). Burst of the Filter Bubble?. Digital Journalism, 6(3), 330-343. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2017.1338145

Hampson, M. (2021). Smart Algorithm Bursts Social Networks’ “Filter Bubbles”. IEEE Spectrum. Retrieved 7 April 2022, from https://spectrum.ieee.org/finally-a-means-for-bursting-social-media-bubbles.

Just, N., & Latzer, M. (2016). Governance by algorithms: reality construction by algorithmic selection on the Internet. Media, Culture &Amp; Society, 39(2), 238-258. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443716643157

Matakos, A., Terzi, E., & Tsaparas, P. (2017). Measuring and moderating opinion polarization in social networks. Data Mining And Knowledge Discovery, 31(5), 1480-1505. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10618-017-0527-9

New America. (2022). Netflix personal account [Image]. Retrieved 8 April 2022, from https://www.newamerica.org/oti/reports/why-am-i-seeing-this/case-study-netflix/.

Siles, I., Espinoza-Rojas, J., Naranjo, A., & Tristán, M. (2019). The Mutual Domestication of Users and Algorithmic Recommendations on Netflix. Communication, Culture And Critique. https://doi.org/10.1093/ccc/tcz025

The Guardian. (2022). The Guardian’s new Burst Your Bubble section [Image]. Retrieved 8 April 2022, from https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/series/burst-your-bubble.

Zuiderveen Borgesius, F., Trilling, D., Möller, J., Bodó, B., de Vreese, C., & Helberger, N. (2016). Should we worry about filter bubbles?. Internet Policy Review, 5(1). https://doi.org/10.14763/2016.1.401