Background

Our perception of information is subject to what we have experienced, thus it is rather unintentional, incomplete and partial. Back in old days we live in comparatively barred environment, when approaches to access information were quite limited and what shapes our views depends on the realities around. As information technologies developed, the Internet thrived and made us conscious of the diversities and varieties of the world. We are able to absorb information and knowledge to a large degree without time and region limits, which in return speed up the growth and building of the Internet. As the population of Internet user surged in a substantial amount, more mature traffic distribution system and operation methodologies are in need to keep up with the growth. As much attention has been paid the role of distribution of information, the notion of ‘filter bubbles’ (Pariser, 2011) occurs. Filter bubble, also known as echo chambers, defined by Pariser (2011), limits news and information access by personalizing searching results, recommended ads and web pages based on one’s searching or viewing history. Seldom attention is paid to how the personalization is formed (some asks for collection implicitly, usually with the notice toast ‘accept the cookies’ with lengthy ‘terms and conditions’, but most of users will not scan carefully what is it in the description) and they are unaware of how their personal data being used. Filter bubbles occur on many platforms, such as short video platforms. TikTok and Kwai are the earliest bunch of short video platforms that thrives in early 2000 that has more than half of the Chinese Internet users. They were both accused of video addiction because the algorithm made users spend plenty of time viewing feeds and so on.

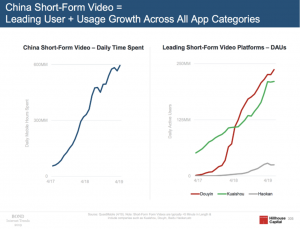

Figure [1]China Short-Form Video Daily Time Spent & Leading Platforms from 2019 Internet Trends Report

For one thing, videos on these video platforms are categorized into different interest fields with labels, while users are ‘stamped’ with interest labels based on viewing history, so that the algorithm system is able to recommend personalized and more accurate contents to their users. For another, the algorithm system on short video platforms adopts interaction mechanism and collaborative filtering to form a ‘pitfall’ for users to gain more staying hours. But there is a difference on traffic distribution strategy between TikTok and Kwai that leads to opinion polarization, specifically ‘urban-suburb’ polarization (Wang, 2018; Liu, 2020).

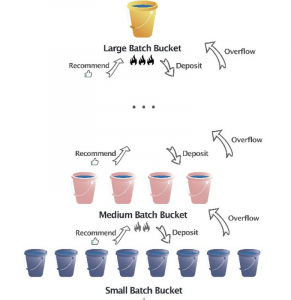

Figure [2] Traffic Distribution System on Short Video platforms

What TikTok applies is ‘centralized’ traffic distribution strategy (Wang, 2018). A fresh launched content will enter a batch of bucket with analysis of its likes, comments, shares and replays etc. The content will flow into a larger bucket if the analysis reaches certain score, so contents with high score will become increasingly popular, occupying the exposure opportunity of less well-received contents or newly published ones. It results in a phenomenon that contents are newsworthy, novel or trendy that become the main community disposition, which in lines with the content preference of TikTok’s major users, who mainly come from urban areas and first or second-tier cities. On the contrary, Kwai maintains ‘decentralization’ strategy, while traffic is comparatively equally distributed (Liu, 2020). Users are more likely to see various contents rather than those with high scores, even viewers are also ‘stamped’ with interest labels. So what displays in Kwai are contents of all walks of lives, mostly ordinary life or grass-root dailies, which attracts users from suburb areas and third-tier and forth-tier cites. That is part of the reason why the community vibe in Kwai presents more obvious than TikTok’s.

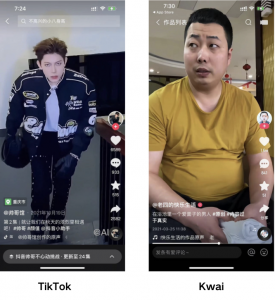

Figure [3] Contents Difference between TikTok and Kwai

As Figure[3] shows, the male on TikTok wears elaborate make-up, trendy jacket and his body shape maintains comparatively fit, while the male on Kwai is bare-face, wearing a wrinkled shirt and his body shape shows otherwise compared to the one on TikTok. Being different as it is, their content variation caused by two filtering algorithms was accused of triggering culture hierarchy as ‘rural–urban dichotomy’ (Liu, 2020). As content differences are, contents on TikTok often intertwined with trendy information that establishes TikTok as a representation of urban China, while Kwai is often described as ‘absurd’, ‘low culture’ with representativeness of rural life (Liu, 2020). Because culture depends on giving things meaning by categorizing them to different positions and the sign of ‘difference’ is a symbol for us to distinguish and recognize culture (Hall, 1997, pp. 329-330; Liu, 2020), I argue that filter bubbles in one way strengthen the culture difference, but in another way reinforce the impression or even stereotype of what the two cultures (urban and rural) should be.

Analyze Filter Bubbles in Critical Way

Undoubtedly, filter bubbles raised many concerns. But why do many platforms still apply it under controversies? What benefits is it for business? I would take a first look at the positive side with a reference with my own experience. Filter bubbles in general improve my shopping experience. Pariser (2011) argues filter bubbles are not great to get people making better decisions together, but it is great for online shopping. Throwing back to the times when e-commerce and retailer business has not developed so well, we usually purchase products with advice of sales assistants, who know the products and our requirements well, so they can recommend suitable products for us. Nowadays, as information technologies develop, the work of ‘recommendation’ is replaced with an algorithm that automatically analyzes our shopping preference, which is comparatively efficient and cost-saving. For commercial purposes, it is definitely profitable. Similarly, I would say the personalized recommendation system on short video platforms improve the rural poverty situation by increasing the exposure of rural agricultural products.

Agricultural products contribute a lot to rural development. The wholesalers between farmers in rural areas and consumers in cities used to take much profits, leading to comparatively slow development in rural areas. With the establishment of logistics system and live steaming e-commerce, farmers are able to sell products directly to consumers in a large amount. Consumers are also able to see the products more clearly by detailed presentation and closer look. With filter bubble’s personalization and state’s policy support to promote industry in rural areas, consumers tend to see products from farmers rather than elaborately packed store with higher prices. As Figure[4] shows, it is interesting to point out that although they are both selling fruits, the way they present and film differ a bit. The camera position on TikTok is carefully placed to show color saturation of the orange, which is more eye-catching; the camera position of the one on Kwai is more like random placement, presenting a normal and ordinary vibe. This is in lines with the characteristics of their contents as discussed above.

Figure[4] Farmers with products on live-streaming on TikTok and Kwai

What Issue may Filter Bubbles Cause

There are negative sides of filter bubbles. One of the biggest issues is that it creates an informational barrier around people that prevents them from seeing other life mode that does not exist in their daily life or they just do not ‘prefer’ them, ‘impression that our narrow self-interest is all that exists’ (Passe, 2017). Because of it, filter bubbles aggravate badly on the rural–urban dichotomy. When individuals on urban areas and rural areas are polarized and only see their side of daily life and lifestyle, and continually are isolated from the other side of ‘world’, a solution will never be reached because filter bubbles reinforced such isolation and dichotomy, Due to the deepening divide between people live in the rural area and urban area and an informative barrier is established, people are more reluctant to communicate between two areas. Furthermore, because the two sides only see content from their respective echo chambers, they cannot have a clear understanding of the area which they are unfamiliar with. Most people get their news from one source, as Panke discusses this by saying, ‘consistent liberals and conservatives often live in separate media worlds and show little overlap in the sources they trust for political news’ (Panke, 2018). This informative barrier means they aren’t exposed to the same information, thus they cannot have common and rural–urban dichotomy established.

Filter bubbles also cause bias and opinion polarization. As Reuters Institute puts it, people gather in media organizations that offer what they believe, and remove other information. In such a community, people tend to cluster together because it generates a sense of belongingness and intimacy. The Internet seemingly embraces the diversity of news and information and unites people, but potentially draws individuals to their own enclosed space (Newman et al. 2017, 30; Andrejevic, 2019). Users cluster on TikTok may find it a ‘cool’ place for self identification, reckoning that urban areas are places with adequate resources and trendy things. To maintain the urban-ness of urban, or to strengthen the ‘cool’ identification, TikTok users, mainly from the urban, may generate bias and discrimination towards people from rural areas, which may exert an negative impact on urban-rural harmony. Similarly, individuals from Kwai, mostly from rural areas, may lack information of what urban-ness be like. Being comfortable of rural surroundings, may reject communication to urban-area, leading to incomplete recognition that causes prejudice.

Conclusion

Finding own characteristics and differentiation in the marketplace benefits business a lot and it is the key to survive with competitive rivals. To maintain their main characteristics, it can be understood that TikTok and Kwai vary so differently on content and the filter bubbles plays a crucial role in strengthening it. But ne issue is the lack of consent or implicit collection from individuals. The filter bubbles of social media and search engines actually combine pre-selected personalization and self-selected personalization to feed contents we presumably already agree with. However, both modes of personalization apply the algorithms to present the content that providers and intellectual algorithms ‘believe’ will be most engaging to individuals based on individual’s gender, age, location, daily search history and past usage. This results that individuals actually have much less control over what they see within social media and search engines. In other words, the content providers such as social media platforms, online shopping, search engines select the contents or topics they think people would potentially ‘prefer’ and isolate people in their own information bubbles without their actual or implied consent. This constitutes an infringement of basic human rights. Every individual has a right to choose what content they would like to see on the Internet. It is unlawful for the content providers to select contents on the behalf of individual users and force them into digital echo chambers to reinforce individual users’ bias without consent from them. More importantly, the lack of access to new information may cause misinformation, bias and polarization. When people are drawn to one side of an argument, they tend to believe the falsities even if it is not reasonable. It is the same when it applies to rural–urban dichotomy, lack of cross communication creates a deep divide between two communities. To break through the information bar, it is encouraged to communicate offline with people or places that are not from existing communities, or search new information manually to add new preferences in the filtering system. Bringing awareness of filter bubbles is also significant in breaking our own ones. More attention should be paid to it and further research is needed to analyze how to balance commercial benefits and user interest in media organizations.

(Word count: 1,915)

Reference

Andrejevic. (2019). Automated Media. Routledge.

Liu. (2020). From invisible to visible: Kwai and the hierarchical cultural order of China’s cyberspace. Global Media and China, 5(1), 69–85.

https://doi.org/10.1177/2059436419871194

Passe. (2017). Homophily, Echo Chambers, & Selective Exposure in Social Networks: What Should Civic Educators Do. The Journal of Social Studies Research.

Panke.(2018). Beyond the Echo Chamber: Pedagogical Tools for Civic Engagement Discourse and Reflection. Journal of Educational Technology & Society.

Pariser. (2011). The Filter Bubble: What the Internet is Hiding From You. New

York, NY: Penguin Press.

Wang. (2018). TikTok vs Kwai: Centralized or Decentralized? Woshipm. Retrieved

from http://www.woshipm.com/pmd/981829.html

Yiu.(2019). Chinese parents struggle with children’s video addiction. Asia Times.

Retrieved from

https://asiatimes.com/2019/07/chinese-parents-struggle-with-childrens-video-addict-ion/