With the popularity of the internet and the development of smart devices, the number of people who have used and are using social media platforms is increasing dramatically. Social media platforms have become an indispensable part of our daily lives as well as online communities for news spread, communication and information-gathering. Before using any social media platform, users need to sign up and agree to the terms and agreements proposed by platforms. And this is one way to regulate user activities. Platform content moderation may seem unknown, but as social media platform users, you have likely experienced it without knowing the term. When using social media platforms, many of you may have experienced your postings or comments being deleted or hidden. And in most cases, users don’t even know which post was penalised for breaking what rules. Sometimes, even the user’s account may be blocked for reasons they don’t even know about. And these are the moderation made by platforms. In this blog, I will introduce the platform content moderation system, its reasons, how it works and existing flaws and possible consequences.

Introduction of content moderation and its importance

As briefly introduced, platform content moderation means the platform’s regulation and handling of content posted by users. More specifically, it refers to the organized activity of managing user-generated content (UGC) posted on platforms. User-generated content can be reviewed before it is submitted on the platform, or after it is published (Roberts, 2019). The basic principle of content moderation is that platforms will publish almost everything uploaded, but will evaluate the posts that users have complaints about or are being detected by algorithm for prohibited content. When users report a post as inappropriate, it is placed in a queue for evaluation by the social media platform’s employees or agents – or, in some cases, other users who take the role of community moderators. The filtering job is normally outsourced to employees in underdeveloped countries, and workers need to make hundreds of choices and decisions every day (Suzor, 2019).

At this stage, platform content moderation does not seem to be complicated. Yet it has plunged many platforms into a huge controversy akin to an abuse of power and has led to criticism from all sectors of society. Back in 2016, Facebook was once criticized regarding a case about content moderation, for deleting a Pulizter-winning photograph “Napalm girl”, also known as “The Terror of War” about the Vietnam war posted by a journalist Tom Egeland because of graphic suffering and underage nudity. Its former Vice President Justin Osofsky explained it as it’s hard to find a balance between “enabling expression and protecting their community” and that led to a mistake (Gillespie, 2019). This has led us to a discussion about the reasons for content moderation, about why would platforms devote so much to it when it can get them into trouble?

With no doubt, the most obvious reason for platform content moderation is economic purpose. Users mean revenue for platforms, so they are trying to build a healthy community for their users and present a good corporate image that can attract more users and advertisers. Platforms are afraid of seeing large groups of users moving to their competitors, regardless of how near-monopolistic, profitable, or established those platforms are. Their efforts for moderation may be motivated by a desire to create a welcoming community to avoid losing users. Users may quit if there isn’t enough moderation to prevent the platform from becoming a toxic place. But people may also leave when there is too much moderation and the platform isn’t open enough but become intrusive for them (Gillespie, 2017). This controversy makes it difficult for platforms to balance the gain and loss when moderating UGC.

As a platform and its user base grow, platforms should be aware that they are dealing with users with diverse cultural backgrounds and values, who rely on the platform to regulate the community and resolve conflicts. This requires platforms to moderate in a way that could protect a user or one group from another and eliminate the offensive, unethical, or illegal content on their platform (Gillespie, 2019). Other than economic pursuits, platforms also regulate to achieve their commitment to create a healthy and encouraging community, and fear of legal intervention and criticism from the public (Gillespie, 2017). As discussed above, we could say that well-structured and sufficient platform content moderation is an essential part of social media platforms.

Methods for content moderation and their limitations

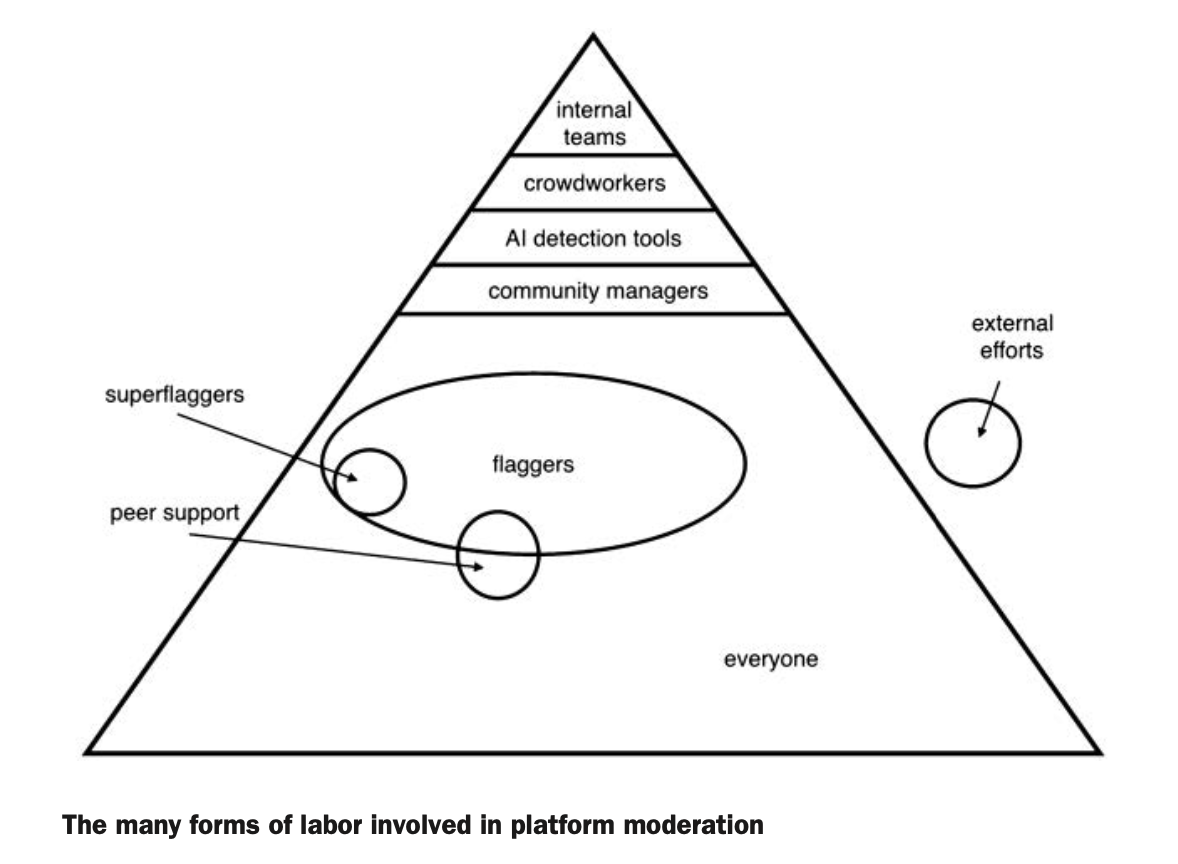

For platform content moderation, platforms will always start by moderating user activities. The tech companies have almost absolute control over their platforms and have various tools for content moderation. There is barely a platform that is as free as its audiences have assumed. As many of you may be aware, almost all platforms have numerous guidelines to regulate all aspects of user behaviour. It’s unlikely that you have read them all but it’s for sure that you need to agree to all the terms before using the platform. As West (2018) has written, platforms have terms of services, privacy policies, community guidelines or standards, copyright policies and a lot more policies and guidelines that set the rules for users. Social media platforms use these terms to outline their expectations with users, and the guidelines described and explained terms about the types of content and user behaviours that are forbidden on or may be published by the platform. Other than these terms and guidelines, as shown in this picture, platforms have numerous forms for content moderation.

Among these content moderation options, we will focus on Artificial intelligence and human moderators. As technology develops, more tech firms have turned to algorithms for solutions. Artificial intelligence (AI) is increasingly used by platforms to screen and moderate users’ posts. Compared to customized reviews by human moderatos, using algorithm to locate and delete forbidden posts requires pre-posting preparation and machine learning processes. Platforms are increasingly using algorithm to detect and remove violative contents as soon as possible before they could be accessed, viewed, or shared by other users. Though adopting algorithmic moderation mechanisms can help the platform to stop the spread of questionable content before it is seen by and influence more users, it has many drawbacks, especially the lack of the ability to comprehend and decode user’s intention, context, idiom or slang (Young, 2022).

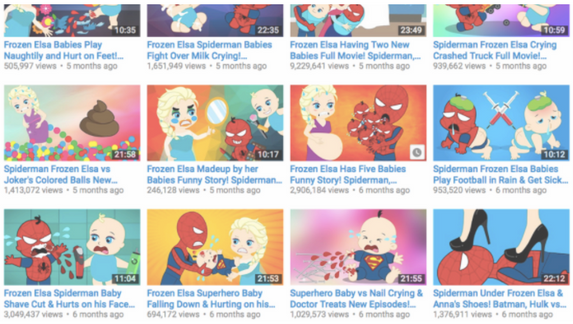

Except for the algorithm’s inability to comprehend information, as the scale of UGC expands on many popular platforms, the process of sorting and filtering user-uploaded contents into approved or rejected categories has become complicated and sometimes is well beyond the capability of the algorithms alone (Roberts, 2019). Due to its limited processing ability, algorithm can also be manipulated by malicious parties to achieve dangerous objectives. By exploiting the platform’s technological infrastructure, algorithms have been used by abusive users to generate and spread offensive content to harass others (Matamoros-Fernández, 2017). As one of the most well-known video-sharing platforms, many of you may have used or at least heard of YouTube. In late 2017, YouTube has drawn attention, discussion and criticism from society because of the failure of its algorithmic moderation. According to Statista (2022), every minute, more than 500-hours of videos were posted to YouTube as of February 2020, equal to almost 30,000 hours’ videos being uploaded per hour. Under such circumstances, it is obvious that the filtering and removal of content by algorithms alone is very inadequate For YouTube. And it was this that triggered the Elsagate incident.

Elsagate refers to a category of YouTube videos that contains animated or live-action dressed-like Disney characters which are labelled as “child-friendly” and recommended to kids. However, those videos are always of low quality and budget, using Disney characters without authorization and making them behave strangely. The majority of videos seem to have Elsa and Spiderman together, with Elsa frequently represented as pregnant. Most of them include meaningless conversations and bizarre activities and contain sensitive and unsafe topics for children such as suicide, alcohol, murder, rape, injections and so on. Instead of being removed by YouTube’s moderation algorithm, such videos were spread widely through keywords and its recommendation algorithm. It was only after a large group of users have them reported and media coverage that YouTube became aware of the problem and began to delete similar videos and block violative user channels (Placido, 2017). Producers were exploiting algorithmic vulnerabilities in YouTube’s platform to upload videos that have violated its platform guidelines. Such videos hurt the children who watch them and anger and disappoint parents who trust YouTube enough to show them to their children.

Algorithmic moderation can speed up the screening process, but many technical gaps need to be filled by other forms of moderation and users can also act as moderators of the platform’s content. Most platforms welcome users to “flag” questionable content by embedding a pop-up window or link in the posts (Gillespie, 2019). When a post is flagged or reported, community moderators will decide whether it should be kept, deleted, and/or the uploader’s account should be suspended or blocked. The front-line moderators who make the judgements are always low-level employees, and they would be trained for some time and internal manuals will be provided for making the decision quickly (Common, 2020). Most first-line moderators are from countries like India and the Philippines where the labour is cheap, distant from the headquarters of the platforms and the users moderated. And the most problematic cases go to the platform’s internal team for review (Gillespie, 2019). Same as algorithmic regulation, such procedures also have loopholes and can lead to problems such as bias and discrimination.

Regardless of the form of content moderation, the final decision-making is always made by platforms’ internal managing teams. The tech firms have teams who set the rules and deal with complex complaints and those members are more likely to be well-educated and wealthy white males. Decisions made by them could entrench biases against minority groups or fail to foster diversity unwittingly. Because of the scale of the information uploaded every day, platforms must use low-cost and high-efficiency moderation systems. If the process takes too long, platforms will lose their headlines and users may be disappointed; but with the number of posts waiting for decisions, mistakes are prevalent when the speed is up. Platforms have also introduced “shadowban” which hides or deprioritizes users’ posts without informing them, and such actions taken by platforms have increased users’ distrust of platforms (Suzor et al., 2019). When such decisions are made, users are frequently questioned but seldom given any explanation regarding why their posts were removed or their accounts were blocked (Suzor, 2019). The lack of transparency and accountability in moderation systems also contributed to users’ mistrust.

Bias is more common when it comes to user report. According to Common’s (2020) study, the popularity of information is considered when evaluating flagged materials. Some contents may be deleted because it’s not newsworthy. This could potentially create a loop in which the information left by the platform will attract more attention and discussion and thus appears more important to the audiences. While deleted content does not receive equal attention and is ignored. And for users, it’s also unfair as some may not report posts for breaking the rules, but because of their personal preferences. They may do this to attack a user or to protect another (West, 2018). Moreover, content moderation workers sometimes need to balance the platform’s profit motivation and demands for user satisfaction as questionable content may attract audiences and clicks to a platform (Roberts, 2016). When humans are involved in the decision-making process, then there is hardly complete fairness. Whether as users or employees or programmers of moderation algorithm, the people who make decisions come from different cultures and have their preferences and opinions.

We have talked about the process, methods and limitations of current platform content moderation systems, posts are always being filtered by algorithm or reported by users, then go to outsourced community moderators for review and decision, and the complex complaints will be forwarded to platforms internal managing team for final decision. Algorithms are always subject to negligence and mistakes, and there can be bias and discrimination when people are involved. This also makes users wonder whether platforms are regulating enough or removing too much. Even though many users treat platforms as free-for-all spaces where they can express themselves however they like, there are boundaries to what is ‘appropriate’ (Young, 2022). Platform content moderation approaches need improvement and more transparency to users is also important. To avoid mistrust and misunderstanding, platforms need to explain to their users why certain posts are deleted or regulated. Platforms should also have better appeal systems, good communication between user and moderator could also be beneficial for eliminating misunderstanding and building trust.

References

Common, M. F. (2020). Fear the Reaper: How content moderation rules are enforced on social media. International Review of Law, Computers & Technology, 34(2), 126–152. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600869.2020.1733762

Gillespie, T. (2017). Regulation of and by Platforms. In J. Burgess, A. Marwick, & T. Poell, The SAGE Handbook of Social Media (pp. 254–278). SAGE Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781473984066.n15

Gillespie, T. (2019). All Platforms Moderate. In Custodians of the Internet (pp. 1–23). Yale University Press. https://doi.org/10.12987/9780300235029-001

Gillespie, T. (2019). The Human Labor of Moderation. In Custodians of the Internet (pp. 111–140). Yale University Press. https://doi.org/10.12987/9780300235029-005

Matamoros-Fernández, A. (2017). Platformed racism: The mediation and circulation of an Australian race-based controversy on Twitter, Facebook and YouTube. Information, Communication & Society, 20(6), 930–946. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2017.1293130

Placido, D, D. (2017, November 29). YouTube’s “Elsagate” Illuminates The Unintended Horrors Of The Digital Age. Forbes. Retrieved April 06, 2022, from https://www.forbes.com/sites/danidiplacido/2017/11/28/youtubes-elsagate-illuminates-the-unintended-horrors-of-the-digital-age/?sh=82d9826ba719

Roberts, S. T. (2016). Commercial Content Moderation: Digital Laborers’ Dirty Work. Digital Media Publications, 12.

Roberts, S. T. (2019). Understanding Commercial Content Moderation. In Behind the Screen (pp. 33–72). Yale University Press.

Suzor, N. P. (2019). Lawless: The Secret Rules That Govern Our Digital Lives (1st ed.). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108666428

Suzor, N. P., West, S. M., Quodling, A., & York, J. (2019). What Do We Mean When We Talk About Transparency? Toward Meaningful Transparency in Commercial Content Moderation. International Journal of Communication, 13(2019), 1526–1543.

Statista. (2022, April, 04). YouTube: hours of video uploaded every minute as of February 2020. Statista. Retrieved April 06, 2022, from https://www.statista.com/statistics/259477/hours-of-video-uploaded-to-youtube-every-minute/

West, S, M. (2018). Censored, suspended, shadowbanned: User interpretations of content moderation on social media platforms. New Media & Society, 20(11), 4366–4383. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444818773059

Young, G. K. (2022). How much is too much: The difficulties of social media content moderation. Information & Communications Technology Law, 31(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600834.2021.1905593