Instagram (Source: Pexel)

Introduction

Have you ever wished digital platforms could take more stern action against harassment? Why do social media companies seem not to take online abuse seriously?

It is nothing new that gender-based harassment permeates the Internet. As we all know, sexual harassment is still a pervasive and unresolved problem in the real world. The progress of digital platforms has facilitated online sexual violence, which is a significant and growing concern in cyberspace (Barak, 2015).

However, abusers would be arrested if they commit sexual harassment in real life. What about in the digital world? The Internet is a place where people hide behind a screen and maintain anonymous online identities. Because of negligent platform governance, abusers expect that they are empowered to post messages with gender-based violence without any consequences.

Especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, the dramatic increase in Internet usage and social media intensity has exacerbated online sexual violence against women (Jatmiko, Syukron & Mekarsari, 2020). Plan International (2020) found that, in Australia, 65% of girls and young women have experienced a spectrum of online harassment on social media platforms. It is higher than the global figure of 58%. And 71% of those who have been exposed to online violence have suffered long-term mental health problems, including lower self-esteem, depression, and anxiety (Plan International, 2020).

According to worldwide statistics, online sexual harassment occurs most common on Facebook and Instagram. To address the situation, Meta launched new policies and features against online harassment recently. But, there is still a lot of work to be done. In this blog, I am going to tell you why social media platforms are responsible for perpetuating online harassment.

Instagram: Intrusive abusive messages

On April 6 and 7, 2022, BBC News, NBC News, and The Guardian reported that high profile women faced ‘revolting’ misogynistic abuse and death threats through direct messages (DMs) on Instagram (McCallum, 2022; Paul, 2022; Sung, 2022). For several months, the Centre for Countering Digital Hate (CCDH) monitored five high profile women’s DMs, including the Countdown presenter Rachel Riley and actress Amber Heard (McCallum, 2022). It is a British non-profit organisation aiming for promoting big tech companies to remove users who spread online hate and misinformation from the platforms.

Rachel Riley, who has more than 500 thousand followers on Instagram, received non-consensual Deep Fake porn images of her face and dozens of images and videos of a penis, including the act of masturbating to her picture in her DMs (McCallum, 2022). Ms Heard, who has over 4 million Instagram followers, had been dealing with death threats in voice notes for a very long time.

Rachel Riley (Source: BBC News)

The researchers collected a total of 8,717 DMs from all five women, including text, audio, image, and video messages (McCallum, 2022). One in 15 of those violated Instagram’s Community Guidelines. Five hundred sixty-seven messages were about “misogyny, image-based sexual abuse, hate speech and graphic violence” (McCallum, 2022).

Ms Riley said the online sexual harassment made her not want to read her private messages because it was disgusting. She (as cited in McCallum, 2022) added:

‘On Instagram, anyone can privately send you something that should be illegal. If they did it on the street, they’d be arrested.’

According to Instagram’s (Meta, 2022a) help centre website on how to report a message, “abusive photos, videos and messages” that you received through DMs on Instagram can be reported. Clearly, voice notes are not mentioned in this policy. The CCDH tried to report the account that sent the audio message death threat to Ms Heard. However, the account was not affected in any way and remained active (McCallum, 2022).

The CCDH also found that one in seven voice messages sent to women contain offensive and abusive information. According to Facebook (Meta, 2022b), they would review the reported audio messages afterwards. But, as the founder and Chief Executive Imran Ahmed said (as cited in McCallum, 2022), audio messages are a forced experience, and there is no way to react instantly to content that may be friendly or offensive.

Not being able to filter or block a voice message in time before hearing violent sexual abuse or death threats is already irreparably damaging to the user’s mental health. Ms Heard (as cited in McCallum, 2022) said that social media, which is a tool for communication for the general public, is a no-go area that she has to compromise and abandon in order to protect her mental health.

Although on April 21, 2021, Instagram announced that they provide several new ways to use proactive detection technology to combat cyberbullying and online abuse (Instagram, 2021), it did not seem to work very well.

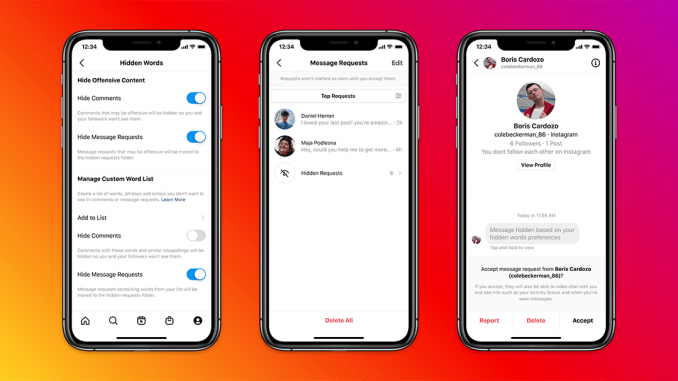

One new feature is filtering abusive messages to hide the messages based on the user’s hidden word preferences (Instagram, 2021). Similar to the existing comment filter, the users can turn DM request filters on in the Hidden Words section under Privacy Settings. Once the function is enabled, a predefined list of offensive terms developed by the company in cooperation with anti-discrimination and anti-bullying organisations will be filtered. Users can also customise their lists of offensive words, phrases and emojis. All DM requests that contain unpleasant information according to the predefined and custom list will be saved to a dedicated folder. Simply opening the folder does not expose you to offensive language unless you choose to click and view the message. Then, you can choose to reply, delete, or report the message.

Instagram’s new feature to filter abusive messages (Source: Instagram Website)

The other new feature is designed to protect the users from someone you already blocked repeatedly contacting you using new accounts (Instagram, 2021). This feature will allow users to block the accounts of the people they want to block and pre-emptively block any new accounts they may create.

From the perspective of potential abusers, Instagram sends stronger warnings when they try to post offensive comments (Mosseri, 2021). According to Instagram, these warning signals get 50% of those comments edited or deleted (Mosseri, 2021). However, I think this warning is only designed for users who are friendly but may inadvertently make mistakes. People who deliberately send abusive messages may ignore the signal and still harm others.

Meta, the company that owns Facebook and Instagram, tells how they enforce policies on their website. The company will not disable any account that violates the Facebook Community Standards or Instagram Community Guidelines just once. After five strikes on the account after repeatedly ignoring warnings and restrictions, Meta will either restrict the account posting content for one month or disable the account forever (Meta, 2022c). This depends on the frequency and severity of the violations. Posting content that breaks the law, for example, child pornography, will not be tolerated. Once an account has been disabled, the company also reserves the user’s right to request a review of the case (Meta, 2022c).

In 2021, Meta launched the Women’s Safety Hub, which provides online safety information for women (Meta, 2022d).

The CCDH found that even when online abuse in private messages was reported to moderators, 90% of them were ignored by Instagram. Researchers reported 253 accounts on Instagram for sending abusive messages. However, they found that 227 accounts were still active after at least a month.

Obviously, these results show that Meta and Instagram still put profit before women’s dignity and rights, which is unacceptable. Although Head of Women’s Safety at Meta Cindy Southworth stated that the company has no tolerance for online sexual violence (McCallum, 2022), rather than just saying, we need to see more effective and practical actions.

Digital platforms should put more effort to combat online abuse

Does online harassment breach our human rights?

Flew (2021) pointed out that freedom of expression is a presentation of the freedom of thought and a way to foster human development. However, he noted, hate speech does promote mistrust and hostility in society, and also negates the human dignity of the victims, which is objectionable.

Clearly, the Internet is no longer a platform that is allowed for absolute freedom of expression, as John Perry Barlow asserted in 1996. After all, harms caused by online harassment and abuse are something that we must not neglect. Online gender-based violence violates women’s human rights. Women who have experienced online violence may self-censor and withdraw from the Internet (Jane, 2017). Moreover, women who have witnessed other women experiencing online violence may silence their voices in the digital spaces (Lenhart et al., as cited in Suzor et al., 2019), depriving their right to Internet access and freedom of expression.

Based on these five high profile women’s experiences of online abuse on the Internet as mentioned in the case study, the concern for young women is expressed. Because these inappropriate, offensive messages of harassment or abuse sent via private messages are not visible to the general public, they are extremely intrusive and disgusting. Young females do not have the life experience and emotional resources that come with age, and online abuse can make them even more vulnerable due to gender-based violence.

Online Sexual Harassment (Source: Mentally Healthy Schools)

Therefore, Flew (2021) threw up important questions that have been debated repeatedly: how do the platforms balance the conflict between freedom of expression and censorship? How do they enforce legal sanctions against hate speech and online abuse? Is digital platform companies’ self-regulation feasible?

As an Internet intermediary, social media companies are responsible for protecting human rights. Every decision made by Internet intermediaries in the governance of the network will directly affect the daily lives of users (DeNardis, 2012). Because of their central role in network communication and their impact on modern society, Internet intermediaries have to assume moral, social and human rights responsibilities for their users (Belli & Zingales, 2017).

Suzor and other scholars (2019) propose that social media platforms remain neutral regarding online abuse and harassment. In addition, in the United States, where Meta is based, Internet intermediaries are not legally liable when their networks have an abuse problem (Suzor et al., 2019). Therefore, in the absence of legal obligations, Internet intermediaries’ role and “responsibility in dealing with online sexual violence is still unclear” (Pavan, 2017, p. 63).

However, some scholars and commentators believe digital platforms are never neutral (Klonick, as cited in Henry & Witt, 2021; Lee, as cited in Henry & Witt, 2021). Because social media companies always aim to make a profit. They may steal user data and sell it to commercial clients (Zuboff, 2019), or favour offensive or controversial views or users to enhance participation and engagement on the platform.

Level Up, a feminist campaign group, found that 29% of the 1000 female participants had experienced sexual harassment on Facebook, especially young women and women of colour (Noor, 2019). The organisation accused Facebook of not attaching importance to online harassment. They point out that the company needs to understand the different types of online harassment and make it easier to report abusive messages (Noor, 2019).

Even though Facebook announced in 2021 that it would strengthen the protection of public figures against online harassment and bullying, for example, by removing malicious pornographic photoshop and sexualised comments (Meta, 2021), there seems to be only a slight improvement.

But what can be understood is that regulating the vast amount of online content is a huge technical and emotional challenge for the platforms (Laidlaw, 2017). Content censors are not well paid, and some suffer from psychological trauma due to prolonged exposure to harmful content (Roberts, 2019; Henry & Witt, 2021).

Social media companies have a duty to care for and protect the safety of women who use the platforms. But unfortunately, even though platforms have the technology to identify whether message content is offensive or not, there are still ways for users to send you unsolicited content. And even when some rude messages are reported, platforms don’t take enough action to stop online harassment and abuse.

Woman’s Voices Get Silenced (Source: Rappler)

Conclusion

Online gender-based harassment and abuse are seen as a major human rights issue. Although Meta has taken some actions to address online gender-based harassment and abuse, there seems to be a significant gap between policy and practice of content moderation (Henry & Witt, 2021).

Platform governance needs to 1) be transparent and accountable; 2) make reporting mechanisms more accessible; 3) hold abusers accountable. Digital platforms should see the safety and rights of women as their top priority.

References

Barak, A. (2005). Sexual Harassment on the Internet. Social Science Computer Review, 23(1), 77–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439304271540

Belli, L., Erdos, D., Fernández Pérez, M., Francisco, P. A. P., Garstka, K., Herzog, J., … & Zingales, N. (2017). Platform regulations: how platforms are regulated and how they regulate us. FGV Direito Rio.

DeNardis, L. (2012). Hidden levers of Internet control: An infrastructure-based theory of Internet governance. Information, Communication & Society, 15(5), 720-738. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2012.659199

Flew, T. (2021). Regulating platforms. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Henry, N., & Witt, A. (2021). Governing Image-Based Sexual Abuse: Digital Platform Policies, Tools, and Practices. In The Emerald International Handbook of Technology Facilitated Violence and Abuse. Emerald Publishing Limited.

Instagram. (2021). Introducing new tools to protect our community from abuse. Retrieved from https://about.instagram.com/blog/announcements/introducing-new-tools-to-protect-our-community-from-abuse

Jane, E. A. (2016). Misogyny online: A short (and brutish) history. Sage.

Jatmiko, M. I., Syukron, M., & Mekarsari, Y. (2020). Covid-19, harassment and social media: A study of gender-based violence facilitated by technology during the pandemic. The Journal of Society and Media, 4(2), 319-347. doi: https://doi.org/10.26740/jsm.v4n2.p319-347

Laidlaw, E. B. (2017). Myth or Promise? The Corporate Social Responsibilities of Online Service Providers for Human Rights. In The Responsibilities of Online Service Providers (pp. 135–155). Cham: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-47852-4_8

McCallum, S. (2022, April 6). Instagram: Presenter Rachel Riley received series of porn messages. BBC News. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-60983593

Meta. (2021). Advancing Our Policies on Online Bullying and Harassment. Retrieved from https://about.fb.com/news/2021/10/advancing-online-bullying-harassment-policies/

Meta. (2022a). How do I report a message that was sent to me or stop someone from sending me messages on Instagram?. Retrieved from https://help.instagram.com/568100683269916

Meta. (2022b). How do I report a voice recording or audio message on Messenger?. Retrieved from https://www.facebook.com/help/messenger-app/2852087488340405

Meta. (2022c). Disabling accounts. Retrieved from https://transparency.fb.com/en-gb/enforcement/taking-action/disabling-accounts/

Meta. (2022d). Women’s Safety Hub. Retrieved from https://www.facebook.com/safety/womenssafety

Mosseri, A. (2021). Introducing New Ways to Protect Our Community from Abuse. Retrieved from https://about.instagram.com/blog/announcements/introducing-new-ways-to-protect-our-community-from-abuse

Noor, P. (2019). Facebook criticised after women complain of inaction over abuse. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2019/mar/04/facebook-women-abuse-harassment-social-media-amnesty

Paul, K. (2022, April 6). High-profile women on Instagram face ‘epidemic of misogynist abuse’, study finds. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2022/apr/05/high-profile-women-on-instagram-face-epidemic-of-misogynist-abuse-study-finds

Pavan, E. (2017). Internet intermediaries and online gender-based violence. Gender, technology and violence, 62-78.

Plan International. (2020). Free To Be Online? (Research Report). Retrieved from Plan International Database: https://plan-international.org/publications/free-to-be-online/

Roberts, S. T. (2019). Behind the Screen : Content Moderation in the Shadows of Social Media. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press,. https://doi.org/10.12987/9780300245318

Sung, M. (2022, April 7). Instagram ‘systemically fails’ to protect high-profile women from abuse, study finds. NBC News. Retrieved from https://www.nbcnews.com/pop-culture/viral/instagram-ignores-dm-abuse-study-rcna23271

Suzor, N., Dragiewicz, M., Harris, B., Gillett, R., Burgess, J., & Van Geelen, T. (2019). Human rights by design: The responsibilities of social media platforms to address gender-based violence online. Policy & Internet, 11(1), 84-103. https://doi.org/10.1002/poi3.185

Zuboff, S. (2019). The age of surveillance capitalism: The fight for a human future at the new frontier of power. London: Profile Books.