image-source from:https://www.vox.com/recode/2020/2/18/21121286/algorithms-bias-discrimination-facial-recognition-transparency

Introduction

With the growth of the Internet, the rise of “platform” companies has dramatically changed the relationship between media and culture. They have become sites of significant cultural disruption and innovation. Machine learning, the basis of what we commonly call “algorithms,” has invested heavily in digital platforms (Crawford, 2021). Algorithms are infiltrating our lives on a massive and pervasive scale. Intelligent algorithms assist advertisers in reaching specific audience groups more quickly by analysing data on users’ browsing and consumption habits and pushing relevant information content to the audiences most likely to interact with them(Flew,2021). Some businesses also use intelligent algorithms, with machines performing complex realistic cognitive tasks, to assist businesses in achieving targeted recruitment and talent screening with the thinking of a computer. Intelligent algorithms based on data analysis, on the other hand, frequently introduce issues such as discrimination and bias. Some of the most common algorithmic biases in life are racial discrimination in algorithmic advertisements, gender discrimination, and price discrimination hidden behind “big data.” According to some scholars, “algorithmic bias” refers to algorithmic programs’ loss of an objective and neutral position in the process of information production and distribution, which affects the public’s objective and comprehensive perception of information.I argue that algorithmic models lead to structural inequalities of race, gender, and class, so algorithms are biased, reflecting cultural biases and social relations. Algorithmic “selection” can lead to discrimination and harm to users. Pasquarelli (2020) distinguishes three types of bias in algorithmic systems: dataset, historical bias, and algorithmic bias. In this blog, I will analyze how algorithms form biases and how to eliminate such biases, mainly from the perspective of dataset and algorithmic biases, using the examples of Facebook and Google?

Facebook iamge- source from:https://www.technologyreview.com/2019/04/05/1175/facebook-algorithm-discriminates-ai-bias/

Google iamge- source from:https://trinity.one/insights/seo/seo-need-to-know-from-google-i-o-2019/

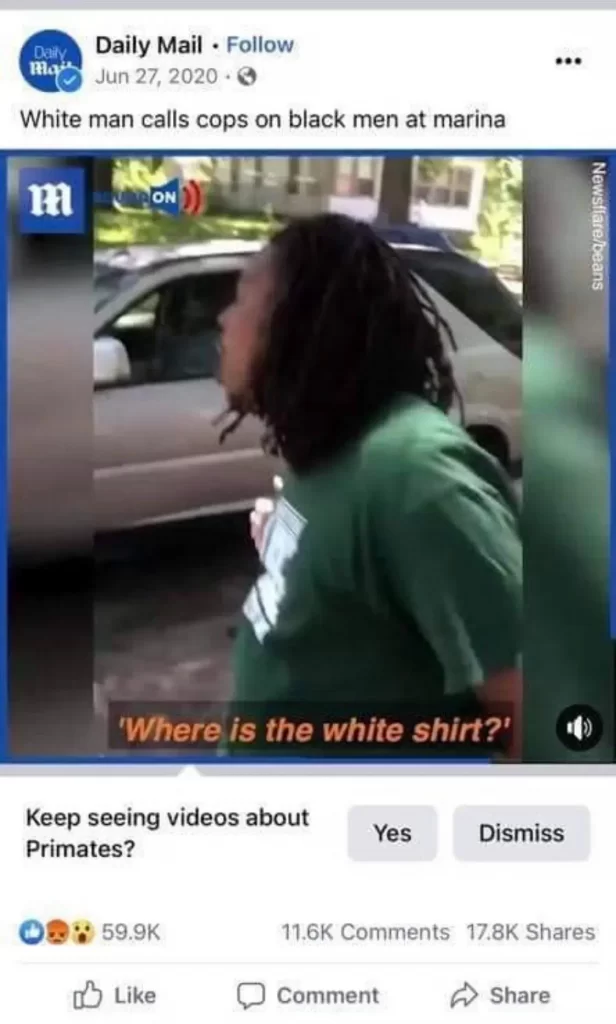

Dataset bias

Dataset bias is defined as data that has been chosen, structured, and labelled to reflect a specific point of view (Bishop, 2021). These data, on the other hand, are frequently introduced by manual modification. In other words, this bias is more like that carried by the algorithm creator themselves. When data is named, the most nuanced process occurs, and stereotyped and conservative taxonomies can cause world distortions, misrepresent social variety, and perpetuate social hierarchies (Crawford, 2021). When a collection of images is tagged with derogatory terms with specific tags, for example, it is always linked to sexual orientation, race, and gender (Bishop, 2021). More specifically, training algorithms frequently begin with people’s daily use of social media, which is then used to create datasets. As we travel across the world, taking photos, text, and doing searches, much of the effort of compiling databases seeps into our daily lives (Draude et al., 2020). It is vital to modify this social and cultural process as a result of the generation of numerous datasets. In this cultural process, it’s easy to skew datasets. This is because data are often collected through machine vision models that create clusters of thousands of associations based on the association of individual vectors. As a result, photographs have some compositional elements that yield gender-related vectors that people identify and classify. This leads to bias in the dataset due to cultural, societal, and technological factors. For instance, Facebook has been repeatedly criticized and sued for discrimination. Facebook’s artificial intelligence video recommendation system incorrectly labelled a video of a black man as “ Gorillas” was discovered and reported after Facebook users who watched the video were prompted to “continue watching videos about primates.” The British tabloid Daily Mail posted the video viewed instead on June 27, 2021, and features footage of black men arguing with white civilians and police officers. Nothing in the video has anything to do with primates. Although a Facebook spokesperson said they disabled the entire topic AI recommendation feature that generated the hashtag as soon as they realized their “unacceptable error.” Unfortunately, this is just the latest example of the “unacceptable error”, moral implications and oppression maintained by AI technology. AI has been observed in the past to be racist and sexist in its bias – particularly the efforts of facial recognition tools to identify people of color. A 2018 study conducted by Joy Buolamwini, a researcher at the MIT Media Lab, found that when photos of white men were shown, AI software correctly identified them 99 percent of the time, but errors increased dramatically when photos of people with darker skin tones were shown. Buolamwini also found that when photos of darker-skinned women were shown , the AI software was able to identify them accurately only 65% of the time.

Facebook’s A.I. labeled the video of Black men as content “about Primates.”

image-source from:https://www.nytimes.com/2021/09/03/technology/facebook-ai-race-primates.html

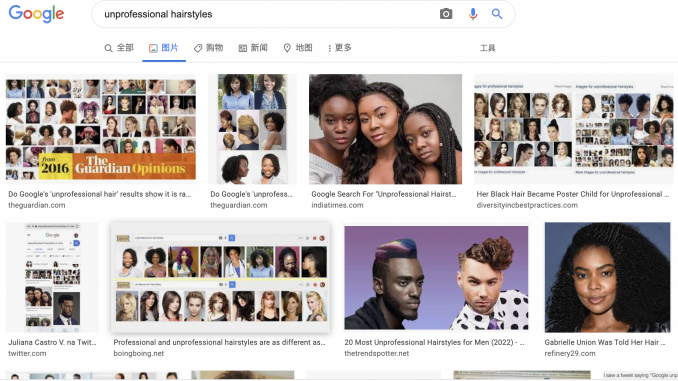

Similarly, Google has had problems. in 2015, Google’s Photos app incorrectly categorized photos of black people as “gorillas.” After apologizing, the tech company appeared to have fixed the biased algorithm. However, more than two years later, Wired magazine found that Google’s solution was to censor search for terms like “gorilla,” “chimp,” “chimpanzee” and “monkey” rather than actually addressing the root of the problem – an artificial intelligence tool with the racial bias of its creators. Furthermore, Safia Noble (2018) shows some examples of how Google’s search engine generates these harmful and discriminating representations. When she looked up ‘unprofessional hairstyles,’ she found several pages of results that heavily favored African American women with ‘afro’ haircuts (Noble 2018). When she searched for ‘black girls,’ she found that half of the top 10 results (50%) were sexualized or pornographic (Noble 2013).Technical and social reasons have resulted in these misclassifications and labelling. Datasets with many associations can technically be used to train Google’s search engine algorithms (Just & Latzer, 2017). This is due to the fact that gender is both fluid and dynamic, as well as multifaceted. These algorithms tend to perpetuate gender patterns that are binary, hierarchical, and difference-based. From a sociological standpoint, Google is a mass commercial platform that frequently leads to discrimination based on public perception. For optimisation purposes, users “train” the algorithms through their searches and clicks. (Noble 2013). Pornographic websites show up when people search for “black females” because they employ a variety of “search engine optimisation” strategies to manipulate algorithms and enhance ranks (Khalil et al., 2020).

unprofessional hairstyles, image- source from:https://www.google.com/searchq=unprofessional+hairstyles&rlz=1C5CHFA_enAU996&sxsrf=APq-WBt_jTsQAB0EoKOop6HHJbpMc1mYw:1649658830068&source=lnms&tbm=isch&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwi5i8SEsov3AhU1T2wGHeALAwUQ_AUoAXoECAEQAw&biw=1440&bih=639&dpr=2

Algorithmic bias

Second, algorithmic bias, also known as machine bias, further amplifies the historical bias and dataset bias that machine learning algorithms have. An algorithm’s automated decision-making process is biased towards specific results when it is optimised or weighted. Recommendation algorithms, for example, favour certain sorts of material for consumers over others. As a result, they favour homogeneous options and are less interested in diversity (Kumar et al., 2020). On the one hand, algorithmic prejudice has an impact on popular culture. Prejudiced automated decision systems are biased towards specific political and social logic, as well as the result of historically unequal allocation of resources and power. In order to protect predetermined social and cultural privileges, strong political and economic organisations are frequently faced with automation. When dealing with questions of power, it’s crucial to analyse who has the right to speak. For example, voter mobilisation techniques based mostly on algorithmic algorithms were used in the presidential elections of Barack Obama, Bill Clinton, and Donald Trump. As a result of political power and interest, platforms used manipulative algorithms. In 2012, Facebook engineers and researchers reported “vote” tests in the journal Nature (Kumar et al., 2020). All Facebook users in the United States were randomly assigned to one of three groups on the day of the 2010 U.S. congressional elections: “social information,” “informational information,” or “control.” The 60 million users assigned to the “Social Info” group were shown an “I voted” button with a link to voting information, the number of Facebook users who reported voting, and a photo of the friend who voted. The control group, on the other hand, did not display any voting-related information. The 6.3 million Facebook users were then matched with public voting records in order to compare their Facebook activity to their voting activity. The researchers discovered that those who received political messages were 0.39 percent more likely to vote, calculating that the “I Vote” button “directly boosted about 60,000 voters and indirectly boosted 280,000 voters through social infections, for a total of 340,000 additional votes.”As a result, it’s critical to highlight algorithm transparency while also supporting algorithmic decision-making that is fair in terms of political power and social institutions. Algorithmic decision making, on the other hand, has been used to reinforce traditional notions and propose material. Advertisers, for example, have leveraged Facebook’s algorithmic advertising strategy to avoid showing employment ads to older users or financial or real estate ads to people from specific towns or nationalities. Make the employment of algorithms more transparent and available to public criticism in general. Furthermore, taking into account who is using the algorithm and for what purpose might aid in addressing concerns of fairness and prejudice in algorithmic decision-making.

Mitigation proposals

How to mitigate algorithmic bias? On the one hand, avoiding algorithmic discrimination necessitates confronting algorithmic bias head-on: on the one hand, openness is the first step towards accountability, and one of the reasons computational prejudice appears so opaque is that we can’t always detect when it’s occurring (or even if an algorithm is in the mix) (Janssen & Kuk, 2016). Even if we recognise that algorithms might be skewed, this does not ensure that businesses will be open about allowing outside researchers to evaluate their AI. This raises a problem for those advocating for more equitable technical systems. On the other hand, always be cautious of algorithms. Develop and apply them in a way that prevents the introduction of personal explicit bias and tries to identify explicit or implicit bias in them. They should also avoid algorithmic discrimination, and operators of algorithms should regularly audit bias and conduct formal and regular audits of algorithms to check for bias. The third reason is that new laws are needed to regulate AI, and some legislators are lagging behind. The Federal Trade Commission is considering a bill that would require firms to verify their AI systems for prejudice (FTC). Also, legislation to restrict facial recognition has been proposed.

Conclusion

In conclusion, it’s vital to recognize how algorithms influence the content we consume, as well as how algorithmic culture has drastically simplified people’s lives. Even when the algorithms’ authors have no intention of discriminating, algorithmic prejudice occurs (Pasquinelli & Joler, 2020). The limitations of machine learning aren’t just technological; they’re also social. Inequalities in socio-historical relationships and power structures frequently result in bias and discrimination in algorithmic systems. Bias and discrimination occur when these inequalities are embedded in algorithmic system data sets and algorithms. An emphasis on social and ethical ideals is essential for reducing bias and discrimination. Change should begin with innate views, even if undefined is the consequence of past bias. Second, increasing the algorithm’s openness and allowing people to understand and appreciate the data’s source would aid the algorithm in making a fair choice.

References

Bishop, S. (2021). Influencer Management Tools: Algorithmic Cultures, Brand Safety, and Bias. Social media + society, 7(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/20563051211003066

Crawford, K. (2021). The Atlas of AI: Power, Politics, and the Planetary Costs of Artificial Intelligence. Yale University Press.

Cotter, K. (2019). Playing the visibility game: How digital influencers and algorithms negotiate influence on Instagram. New Media & Society, 21(4), 895-913.

Draude, C., Klumbyte, G., Lücking, P., & Treusch, P. (2020). Situated algorithms: a sociotechnical systemic approach to bias. Online Information Review, 44(2), 325-342. https://doi.org/10.1108/OIR-10-2018-0332

Flew, T (2021) Regulating Platforms. Cambridge: Polity, pp. 79-86

Janssen, M., & Kuk, G. (2016). The challenges and limits of big data algorithms in technocratic governance. Government Information Quarterly, 33(3), 371-377. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2016.08.011

Just, N., & Latzer, M. (2017). Governance by algorithms: reality construction by algorithmic selection on the Internet. Media, culture & society, 39(2), 238-258. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443716643157

Khalil, A., Ahmed, S. G., Khattak, A. M., & Al-Qirim, N. (2020). Investigating Bias in Facial Analysis Systems: A Systematic Review. IEEE Access, 8, 130751-130761. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3006051

Kumar, M., Roy, R., & Oden, K. D. (2020). Identifying Bias in Machine Learning Algorithms: CLASSIFICATION WITHOUT DISCRIMINATION. The RMA journal, 103(1), 42-48.

Pasquinelli, M., & Joler, V. (2020). The nooscope manifested: Artificial intelligence as instrument of knowledge extractivism. Artificial Intelligence and Society.