Introduction

This is a great era that people have been waiting for, but it is also a time when people are overwhelmed by the speed and efficiency of information flow. While we are enjoying the enormous benefits of the Internet age, its negative effects are also beginning to emerge: information overload, false information, cybercrime and so on. Hate, an innate human emotion, has also found its best outlet and spread on the internet. Hate speech was first discussed in the early twentieth century, and after WWII, European countries began to pass legislation prohibiting it for reasons such as the suppression of racial and religious hatred. The Nuremberg trials of Nazi war criminals were the first to draw a link between speech and public behaviour (Maravilla, 2008, p. 144). At the time, hate speech was mostly synonymous with racial hatred. The main site of hate speech has shifted to cyberspace as a result of the development of the Internet. And the development of the internet has made the dissemination of speech extremely fast and wide, allowing the exercise of the right to freedom of expression to acquire entirely new means and greatly expanding the scope and audience for the dissemination of information. Because of the ease with which hate speech can spread online, if freedom of expression is not effectively and reasonably regulated, it can contribute to the spread of hate speech and even lead to a rise in hate crimes. In this article, I will provide an in-depth analysis of online hate speech, from its definition, features, and whether algorithms can solve the problem of online hate speech.

Definition

A major reason why online hate speech is so difficult to regulate is that it is hard to define. The UN Secretary-General Pan Jiwen describes online hate this way: “The use of the latest technology to spread the oldest fears.” Distinctions in terms of the target of hate speech can lead to different definitions. In terms of racial identity, Richard Delgado and Jean Steffancic (2017) claims that hate speech consists of racial slurs, nicknames, or other harsh words intended solely to harm or marginalize another person or group. For a broader group, Anthony Cortese (2006) points out that hate speech denigrates people based on their religion or race, age, gender, physical condition, physical or mental impairment, sexual orientation, and other factors. Put together, hate speech implies rejection, hostility, a desire to hurt or destroy, a desire to turn the target group away from their ways, to be silent or vocal, to declare war on them passively or actively, and to be actively disrespectful, dislike, disapprove of, or demean others (Parekh, 2006, p. 214). Online hate speech is a new manifestation of hate culture on the Internet, which disseminates issues and content from the real world. Thus, online hate is a form of hate culture, that uses advanced online communication technologies to spread ideas, mobilise organisations and direct actions.

Features of online hate speech

In the following section, I will discuss five features of online hate speech that make it more difficult to tackle.

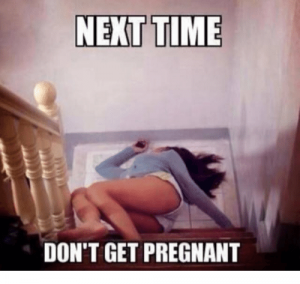

1. Hate speech comes in many forms on the internet

Hate speech can take the form of both verbal and written expressions, as well as symbolic speech. Because of the variety of media forms available on the Internet, every Internet user can use media forms such as pictures, audio and video in addition to text. Memes, which combine text, images, and even animations, have become a popular form of hate speech on the internet. Memes’ symbolic expressions often take the form of jokes and sarcasm, and they don’t directly address prejudice, discrimination, or hatred, making them difficult to control. Please see below for the memes (see figure 3). Taken in isolation, the text is not insulting and may even be good-humoured suggestions about sexual health and family planning (Ullmann & Tomalin, 2019, p. 78). But, When accompanied by this image, the text’s meaning shifts dramatically, and misogynistic connotations emerge (Ullmann & Tomalin, 2019, p. 78).

2. Individual accountability is hampered by anonymity

Advances in internet technology, network access, and the availability of smart devices have made it possible for an increasing number of people to access cyberspace. In the era of traditional media, the Internet has lowered the threshold for publishing information, resulting in the unhindered and widespread publication of hate speech and its regulation only through ex post facto censorship. In addition, the mobile and anonymous nature of the Internet makes expressions of hate effortless in an abstract environment that transcends the traditional realm of law enforcement and makes it an ideal tool for extremists and purveyors of hate speech to incite hatred (Banks, 2010). Anonymity gives internet users a layer of psychological protection and allows them to participate in an orgy of hate speech regardless of the pressures of reality.

3. Fast and widespread dissemination of internet information

Besides anonymity, the instantaneous nature of the internet has also pushed the accelerator button for the spread of hate speech. The rate at which relevant platforms regulate online hate speech frequently falls short of the rate at which it spreads, making it very difficult to effectively govern hate speech as it spreads. Developed mobile communication technology allows everyone to disseminate information via smartphone or computer tablet. This means that any communication is a global one. On the internet, information can be quickly disseminated to any part of the world, and the broad range of dissemination makes it harder to monitor and regulate hate speech.

4. Prone to clustering behaviour

Clustering behaviour can be divided into two categories. The first is aggression by an otherwise dominant group against an inferior group. Individuals engaging in this type of group behaviour frequently seek identity, establish group connections, find a sense of presence, and gain attention. The second type of group behaviour is a square effect in the anonymous environment of the internet, similar to street vandalism. They hide under anonymous accounts and participate in group activities, imitating the behaviour of others and seeking outlets for emotional stress.

5. The seriousness of the consequences of dissemination

Waldron(2012) emphasised that hate is not regulated as a motive for hate speech but concerning the consequences of hate speech. Hate speech undermines this vital public good and deprives people of the dignity they should have in society in a well-ordered society in which everyone has liberty from hostility, violence, and discrimination. Why can people be harmed by online hate speech? The insulting and intimidating nature of the discourse is one of the reasons, but even more so because of the unequal power relationship between the two sides. Those who are dominant in society are insensitive to hate speech and ignore the oppression of carnivorous groups by online hate speech. If hate speech is tolerated without limits, minority groups may become increasingly silent and marginalised as they become less expressive out of fear.

Figure 4. https://statusbrew.com/insights/facebook-algorithm/

Can algorithms solve the hate speech issue?

How to implement effective regulation of online hate speech has been a recurring struggle throughout the history of the Internet (Flew, 2021, p. 19). At the moment, companies like Facebook and Twitter are implementing technology that combines machine learning algorithms with human vetting to increase the efficiency of coping with hate speech. So, can smart technology solve the problem of recognising the meaning of human speech? I would like to take the internet technology company Facebook as an example of how Facebook has acted and worked to regulate online hate speech in the past. Facebook has been claiming that the level of its intelligent identification technology has been improving rapidly and that it will actively remove most hate speech before users report it. Facebook reported in Q4 2020 that 6.3 million cases of bullying and harassment on Facebook were actively identified and removed in a single quarter, and the data shows this was all thanks to advances in AI (“Facebook’s latest report on how it tackled hate speech and bullying in Q4 2020”, 2021). However, the data show that this is not the case. According to Facebook data from 2018, the AI system was capable of removing 99% of terrorist propaganda and 96% of nudity, but it only identified 52% of hate speech (Zuckerberg, 2018). While investing a lot of money and manpower in AI development and stressing that AI recognition can be very accurate, technology companies continue to emphasize the limitations of their algorithms and their vulnerability to complex human language systems, attributing controversial incidents to imperfect AI. For example, in 2019, Facebook’s CTO stated that: “And so our previous systems were very accurate, but they were very fragile and brittle to even very small changes if you change a small number of pixels (TARANTOLA, 2020)”. The vulnerability of AI is that it addresses one pattern of hate speech that is currently emerging but may not be able to address new patterns of hate speech. Facebook has even publicly announced the launch of the Hateful Meme Challenge, where US$100,000 will be awarded to anyone who can write the code for an algorithm that allows AI to automatically identify pluralistic hate speech. Even industry giants such as Facebook still face technical difficulties in identifying hate speech online. On the one hand, it has to invest a lot of energy and money in the development of artificial intelligence systems in the hope that AI recognition can be processed quickly in the face of the huge amount of content that is rapidly generated on its servers. On the other hand, the complexity of online language symbols, the limited nature of algorithms and the imperfection of artificial intelligence can only be acknowledged, and a great deal of manual recognition is still required.

Conclusion

Throughout the history of human society, the phenomenon of hatred has never been interrupted, and the impact of hatred on human civilisation is far-reaching, as it leads to confrontation, division and even war. Internet hatred is an extension of the culture of hatred in the real world. Through the Internet, hatred has broken through the constraints of public expression and time and space and has rapidly spread from an old concept to a global reality. The Internet has provided a new platform for the dissemination of hate culture in the real world. Online hate speech has become a shadowy corner of the Internet world, with its more insidious and rapid mode of transmission, and an expanded sphere of influence. There is a growing sense that we are living in a world that is becoming increasingly torn apart. In a reality where online hate is becoming more and more prevalent, internet technology companies are the main actors in regulating hate speech instead of states or governments and are constantly at odds with states, advertisers, the public and others. While technology companies are reluctant to take on this role, they can only attempt to strike a balance between risk avoidance, calculating costs and benefits, restating corporate values and responsibility, identifying and judging the speech content, and guiding users towards self-regulation. And imperfect algorithms will remain the primary tool for technology companies to regulate hate speech.

Reference

- Banks, J. (2010). Regulating hate speech online. International Review of Law, Computers & Technology, 24(3), 233-239. doi:10.1080/13600869.2010.522323

- Cortese, A. J. P. (2006). Opposing hate speech. Westport, Conn: Praeger Publishers.

- Delgado, R., & Stefancic, J. (2017). Critical race theory : an introduction (Third edition. ed.). New York: New York University Press.

- Facebook’s latest report on how it tackled hate speech and bullying in Q4 2020. HT Tech. (2021). Retrieved 6 April 2022, from https://tech.hindustantimes.com/tech/news/facebooks-latest-report-on-how-it-tackled-hate-speech-and-bullying-in-q4-2020-71613104006704.html.

- Flew, T. (2021). Regulating platforms. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Maravilla, C. S. (2008). Hate speech as a war crime: public and direct incitement to genocide in international law. Tulane journal of international and comparative law, 17(1), 113.

- Parekh, B. (2006). Hate speech: Is there a case for banning? Public policy research, 12(4), 213-223. doi:10.1111/j.1070-3535.2005.00405.x

- TARANTOLA, A. (2020). Facebook deploys AI in its fight against hate speech and misinformation. Retrieved 6 April 2022, from https://www.engadget.com/facebook-ai-hate-speech-covid-19-160037191.html

- Ullmann, S., & Tomalin, M. (2019). Quarantining online hate speech: technical and ethical perspectives. Ethics and information technology, 22(1), 69-80. doi:10.1007/s10676-019-09516-z

- Waldron, J. (2012). The Harm in Hate Speech. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.

- Zuckerberg, M. (2018). A Blueprint for Content Governance and Enforcement. Facebook. Retrieved 6 April 2022, from https://m.facebook.com/nt/screen/?params=%7B%22note_id%22%3A751449002072082%7D&path=%2Fnotes%2Fnote%2F&_rdr.