Introduction

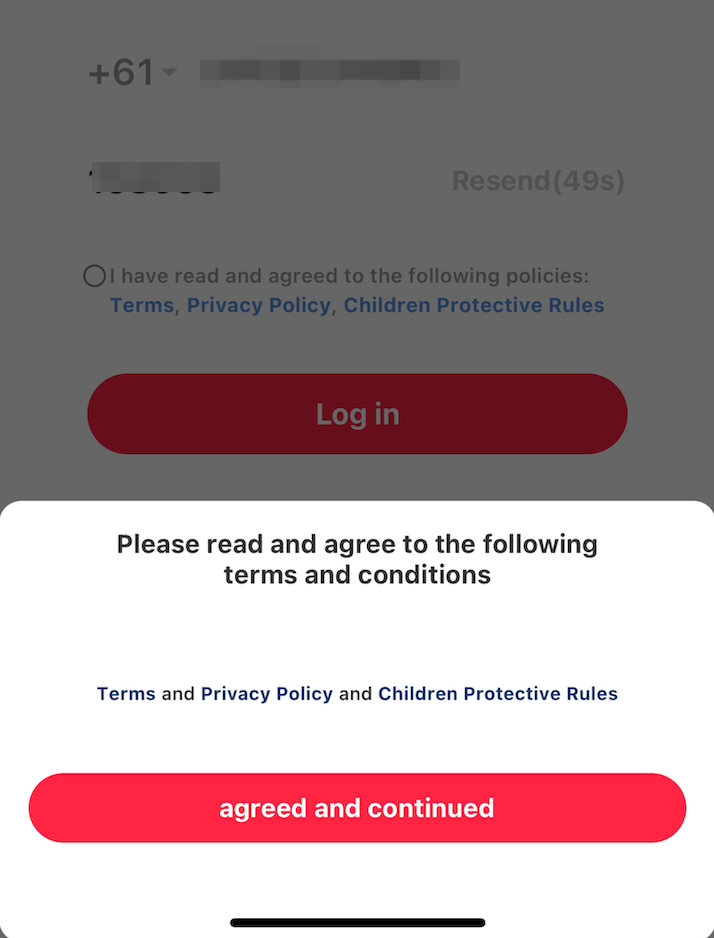

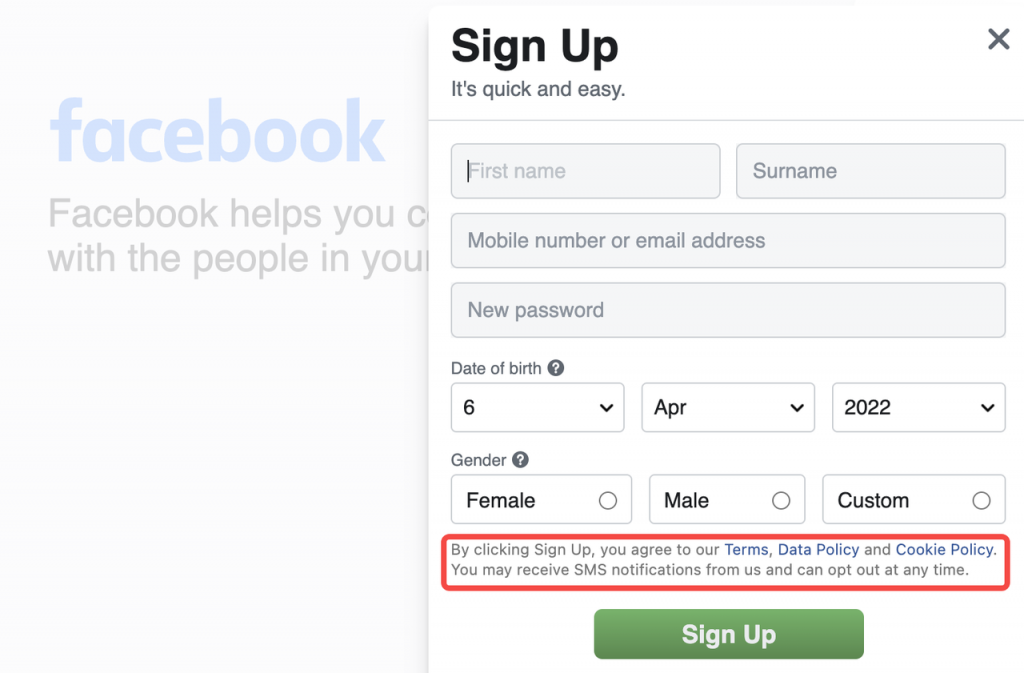

Have you ever been notified to click and agree on the permission of the terms and privacy policy? And have you ever read it, or do you simply click the agree button and continue to log in? Or have you ever noticed that you have unconsciously agreed to the platform’s terms, data policy, and cookie policy when you click the sign-up button?

Users are handing over their personal data to the companies of digital platforms. I believe most of you never go through the terms that you are given permission to use. Given the complexity of these terms, as Flew (2019) pointed out, users may not be able to understand all of them. Besides, there is no chance or space for users to negotiate the terms and enjoy the full service without agreeing on the terms. In this case, you may be allowing the platform to collect your personal data.

Users voluntarily providing their personal data is the beginning of misuse of personal data. What happens now is as Frank (2015) described, while the companies of the digital platform hide their action in the privacy agreement, our private lives are exposed to the public. According to the World Economic Forum (2016), the combination of personal data comes from volunteered data that are provided by users themselves, observed data that are analysed by digital footprints, and inferred data that are analysed based on volunteered data and observed data. And GDPR defined personal data as data that can be inferred to identify a natural person (2018).

Companies’ use of personal data can be seen in algorithms. Personal data is the composition of the database and can be used and analyzed by algorithms. Along with the development of technology and digital media, to provide a better user experience, companies on digital platforms are collecting and using personal data. For example, algorithms were invented under the needs of this context. And one of the most important and common is its use on the digital social media platform to keep users staying on their application, as Little Red Book has done. The algorithms will calculate your interest based on your previous viewing footprint and the likes you put on social media posts, then provide the content that interests you on the homepage.

But digital platforms’ growing control of users’ personal data raises the concern of data being misused. In this blog, we will closely look at the existing situation of the misuse of personal data and you will find out how companies take advantage of users’ personal data, in the context of Didi Chuxing and Big data discriminatory pricing.

Case study – Didi Chuxing

What is the worst thing that can happen if your personal data are misused? Starting from the perspective of national safety, the company’s misuse of personal data could compromise national security.

Didi Chuxing owns a huge database. Didi Chuxing is an application that provides vehicle transportation, similar to Uber in Australia. It provides instant online car-hailing services for the users. This application already covers all urban areas in China. In addition, according to Tianyancha, a leading business query platform in China, as of March 31, 2021, the annual active users on Didi’s global market exceeded 493 million, and the average monthly active users on the platform were 156 million. In addition to having control over the entire traffic data, Didi Chuxing also has fully acknowledged users’ identity, ID numbers, bank card numbers, mobile phone numbers, home addresses, company addresses and so on.

(Source: South China Morning Post)

Didi Chuxing’s misuse of personal data is putting China’s political safety in a risky position. On June 30, 2021, Didi Chuxing was officially listed on the New York Stock Exchange quietly. As Flew discussed (2019), when all the information becomes computable data, the individual and group’s future behaviours would become predictable based on past data analysis. Anyone can make any analysis based on this database. For an instant, Wang, Xu, Peng, and Zhang (2019), successfully analyse users’ spatial travel regularity based on the big data from Didi. While their research is good, it also proves that seemingly unrelated pieces of data can be put together to make a clear conclusion. As they pointed out, the analysis of citizens’ travel behaviour can reflect the overall travel characteristics of a city. In other words, this data can reflect the overall travel characteristics of the whole country if there is enough data sample. A simple name can locate a person. With a little more data, the spatial travel regularity of a whole city can be concluded. If the database is large enough, it can predict everything about a whole country. On July 04, 2021, the Cyberspace Administration of China announced that Didi Chuxing has been removed from the service due to serious violations of personal information collection and use. Although there is no conclusion on whether Didi sells all Chinese data to the United States, the Chinese government confirms Didi Chuxing’s misuse of personal data and Didi Chuxing has a ban on use in China.

(Source: Cyberspace Administration of China)

Case study – Big Data Discriminatory Pricing

Let’s narrow down to see how the misuse of personal data could impact our daily life by taking a close look at the phenomenon of big data discriminatory pricing.

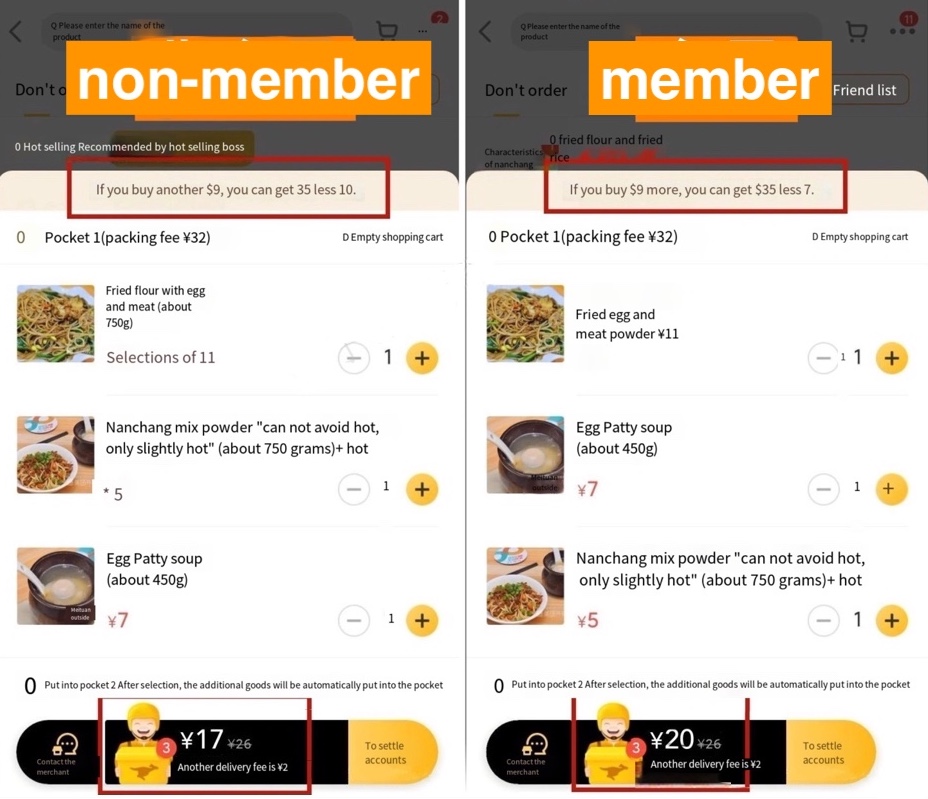

The companies of the digital platform are making money using our personal data. The emergence of big data discriminatory pricing is based on companies misusing users’ personal data. As it is mentioned above, personal data is the composition of the database and be analysed by algorithms. As Wen (2021) pointed out, the algorithm will customize prices for each customer based on the user’s personal data, such as an address, shopping history, and consumption habits. With the development of technology and the collection of users’ data, the database is big enough for the algorithm to sort out and analyse the basic information, consumption habits, consumer preferences and other user data of customers on the platform, describe the personal consumption characteristics of customers, and form user portraits. And based on such analysis, the digital platform companies are able to automatically adjust the prices of the goods during the sales. For example, some users who do not use the platform very often and have a low purchase history can enjoy a better price. The behaviour by which the company sets different prices for different customers based on algorithm analysis of user patterns is called discriminatory pricing in big data. Wen also draws a conclusion that, compared to non-discriminatory pricing, the company could benefit more from setting discriminatory prices.

Take one of the most famous Meituan as an example. It is one of the most popular online shopping platforms that provide localization services, including entertainment, food delivery, travel, and other services. On December 14, 2021, a user ordered the same food at the same time from a different account in Meituan by chance. One of the accounts logs in as a non-member user who is a newly registered Meituan shows 17 dollars with the food. However, the other logs in to the Meituan account logs in as a member user shows 20 dollars with the same food. Meituan collects and summarizes consumer preferences, consumption levels, and other data information through technical means, analyses consumer data information, and then floats the prices of goods or services randomly to implement price discrimination against users.

(Source: Zhi Hu)

Another example of big data discriminatory pricing happens to Netflix’s users. According to Shiller’s (2013) analysis, with the old Netflix setting prices, which are based on demographics, Netflix’s profits can rise by 0.3 percent. However, if it set its price with the analysis of the algorithm, which is based on users’ Internet browsing history, the company is able to estimate the maximum price a user would be willing to pay. In this circumstance, this could drive Netflix’s profits up by 14.55 percent.

The growing control of the digital platform of users’ personal data raises the concern of data being misused. As Etye (2019) mentioned, under the scenario of using big data discriminatory price setting, consumers no longer have the opportunity to make a profit from the market. And the position of consumers as market participants is also weakened. Salil K (2021) also argues that the discriminatory setting of prices in big data can limit consumers’ choices and prevent them from making their own decisions. Along with the improvement of the algorithm, it can be more and more precise about the preferences of users. In this case, rather than seeking the product among all the options, consumers may only have one simple choice. We are losing control of our lives. The companies of the digital platform have far too much control over our personal data. While giving out all our personal data, we are losing control of our personal data, furthermore, our personal life.

Conclusion

In conclusion, from the above case studies of Didi Chuxing and discriminatory pricing of big data, we can see the facts that our personal data have been misused by companies on digital platforms. And it can not only affect our personal interests in our daily life, and it can also be a threat to national security. Under this circumstance, the ownership of users’ personal data by digital platform companies needs to have a clear limitation and the awareness of the ownership of our personal data needs to rise.

Data plays an important role in today and future society. As World Economic Forum describe data as the ‘oil’ in today’s digital era. Compares the value of data with oil and shows how important data are in the current digital age. Also, as Harari (2018) pointed out that owning the data means having access to the whole world. The future is taken care of by the one who owns all the data. A more detailed and strict regulation needs to be applied under the concern of the misuse of personal data.

Besides, we as users should own more right to know more about our personal data situation. Pasquale (2015) describes today’s world as a “one-way mirror”, in which digital platform companies have every acknowledge of us users. They use all the personal information they gather about us users to make predictions and provide information that we need to know about the future. In other words, these digital platform companies, or the one who owns users’ data, are controlling the information we were received. However, we as the users, have zero control over what personal data they have about us, and how the algorithm works. This is a concern when we don’t have the full knowledge of the way these companies use our data. On the other hand, rather than enjoying and benefiting from all the convenience that the digital era has brought to us, we as users should take more responsibility to be more careful about the permission of our own personal data that we give out. At least, please take a minute to think before you post all your personal information online, or when you try to sign up for a new account on any online social media platform.

Reference

Andrejevic, M. (2019). Automated Media. Milton: Routledge.

Boer, R. (2021). Socialism with Chinese Characteristics: A Guide for Foreigners (1st ed.

2021.). Singapore: Springer Singapore Pte. Limited.

Harari, Y. N. (2018). 21 lessons for the 21st century. Random House.

Just, N., & Latzer, M. (2017). Governance by algorithms: reality construction by algorithmic

selection on the Internet. Media, Culture & Society, 39(2), 238–258.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443716643157

Liu, W., Long, S., Xie, D., Liang, Y., & Wang, J. (2021). How to govern the big data

discriminatory pricing behavior in the platform service supply chain?An examination with a

three-party evolutionary game model. International Journal of Production Economics, 231,

107910–. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2020.107910

Mehra, S. K. (2021). Price Discrimination-Driven Algorithmic Collusion: Platforms for

Durable Cartels. Stanford Journal of Law, Business & Finance, 26(1), 171–221.

Personal data. (2018, May 4). Retrieved April 8, 2022, from General Data Protection

Regulation (GDPR) website: https://gdpr-info.eu/issues/personal-data/

Pasquale, F. (2015). The black box society : the secret algorithms that control money and

information. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Reuters. (n.d.). The app logo of Chinese ride-hailing giant Didi seen through a magnifying

glass on a computer screen showing binary digits in this illustration picture taken July 7,.

Retrieved from https://www.scmp.com/tech/big-tech/article/3162991/didi-chuxing-

co-founder-leaves-chairman-position-payment-subsidiary

Shiller, B. R. (2013). First degree price discrimination using big data (p. 32). Brandeis

Univ., Department of Economics.

Steinberg, E. (2020). Big Data and Personalized Pricing. Business Ethics Quarterly, 30(1),

97–117. https://doi.org/10.1017/beq.2019.19

Tianyancha. (2021). Retrieved April 8, 2021, from :

https://m.tianyancha.com/company/241819175

Flew, T. (2019). Platforms on Trial. Intermedia, 46(2), 18–23.

https://eprints.qut.edu.au/120461/

Flew, T. (2021) Regulating Platforms. Cambridge: Polity.

World Economic Forum. (2021). Personal data: The emergence of a new asset class.

Wen, P. (2021). Seller’s Pricing Discrimination Strategies under Adoption of Online Big

Data Technology. 2021 International Conference on E-Commerce and E-Management

(ICECEM), 201–206. Piscataway: IEEE.

https://doi.org/10.1109/ICECEM54757.2021.00047

Yongdong, W., Dongwei, X., Peng, P., & Guijun, Z. (2020). Analysis of road travel

behaviour based on big trajectory data. IET Intelligent Transport Systems, 14(12), 1691–

https://doi.org/10.1049/iet-its.2019.0785

Retrieved from https://mlexmarketinsight.com/news-hub/editors-picks/area-of-expertise/data-

privacy-and-security/personal-data-legislation-tops-the-agenda-as-chinas-political-

assemblies-kick-off-meetings