Introduction:

The Internet provides us with a global platform and a way to communicate with people worldwide in real-time (Future Learn, as cited in Sunstein 1994 and Yoo 2010). Social media has become an important port for disseminating social information, ideology, and culture. The Court unanimously ruled that the Internet is a free speech zone (ACLU). This means that the public can build their views and expressions with the help of the openness and liberalism of cyberspace and realize the construction and display of their social consciousness. However, when users enjoy the freedom of expression, the different ideologies produced by citizens in social life or cultural groups will be concentrated, which will lead to the collision between views or beliefs, and finally lead to a new crisis: hate speech. As a contradiction that has accompanied our human civilization for centuries, hate speech has gradually evolved into a serious social problem with the extension of the Internet, affecting people’s vision of peace and social stability. Hate speech is considered one of the most intolerant and xenophobic acts today (Latour & Perger… Otero, 2017). If not addressed, hate speech is likely to lead to broader acts of violence and conflict, undermining the cohesion of democratic societies, the protection of human rights and the rule of law (Council of Europe). Due to the changeable international situation, local conflicts still exist, and online hate speech will ferment day by day, which will need to be reflected.

There are many speculations about the causes of this phenomenon, but I think the most influential is the spread of false news. The Internet promotes social groups to participate in politics. However, the personalized algorithm recommendation of social media platforms amplifies existing beliefs and leads to group polarization, which promotes the spread of false information and deepens the influence of extremism, which gives birth to hate speech (European Foundation For South Asian Studies ). Therefore, this blog will take platform racial discrimination as phenomenon research, search how fake news increases hate speech, and explore the governance of public opinion manipulation hidden under the platform.

Fake news under the post-truth:

Post-truth politics is often used to explain the emergence of fake news controversies (Barrera & Guriev….Zhuravskaya, 2020). Cambridge defines post-truth as the idea that people are more likely to accept information based on emotions or beliefs than arguments based on facts (Cambridge Dictionary). The post-truth era has become a social phenomenon which inspires people’s emotions rather than guiding logic, making them more likely to ignore concrete evidence and suggesting to the public that anything based on beliefs can be considered correct and valid (Wardle & Derakhshan, 2017). The post-truth era has paralyzed the public’s reasoning and distorted their sense of right and wrong. Post-truth creates a moral grey area where lies can be rationalized and have no negative consequences (Keyes, 2004). This has led mainly to the creation and spread of rumors, and fake news and has contributed to the implementation of conspiracy theories (Al-Radhan, 2017).

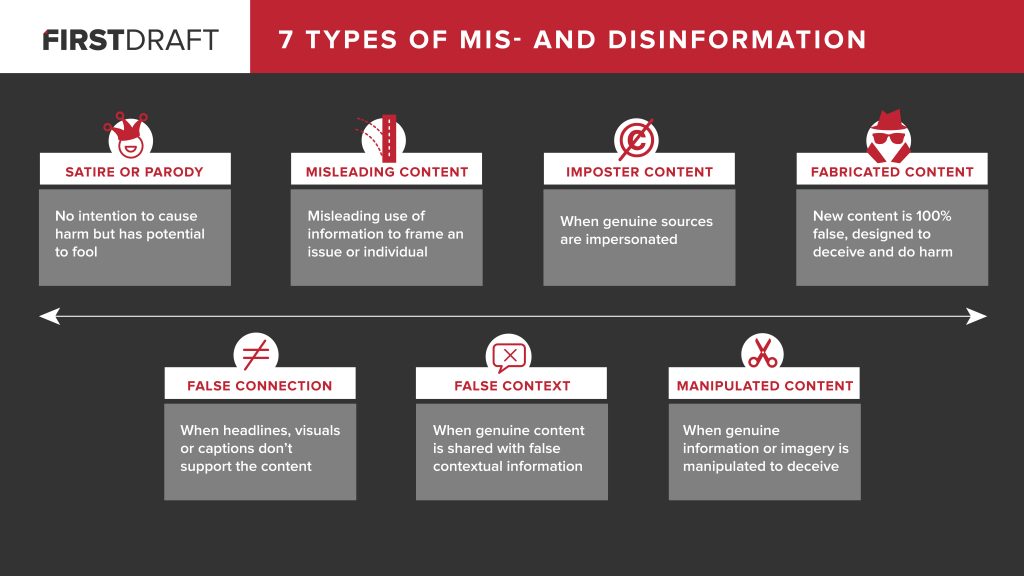

Fake news possesses a broad definition: it is false or misleading content that circulates in electronic and communication media presented in the form of news (Higdon, 2020) .As shown in Figure 1, this visual image creates an ecosystem of fake news and distinguishes between seven types (Wardle, 2017). It is worth noting that the second interpretation of fake news was used mainly by former US President Donald Trump, he would often classify media reports about his disadvantages as fake news, but in most cases, he did not provide a fact-based rebuttal (Holan, 2017). In such cases, fake news gradually evolved into psychological manipulation, which is similar to the gaslight effect. A person will cause others to doubt their perceptions or believe that events are unfolding in a way that does not correspond to reality by lying or exaggerating the facts (Sarkis, 2017). It follows that the purpose of fake news is to conceal the truth and thus influence public opinion. It is worth considering that once public opinion is out of control and triggers unintended consequences, an outbreak of hate speech will follow.

Figure 1: seven categories of fake news (Wardle, 2017).

Fake news on YouTube:

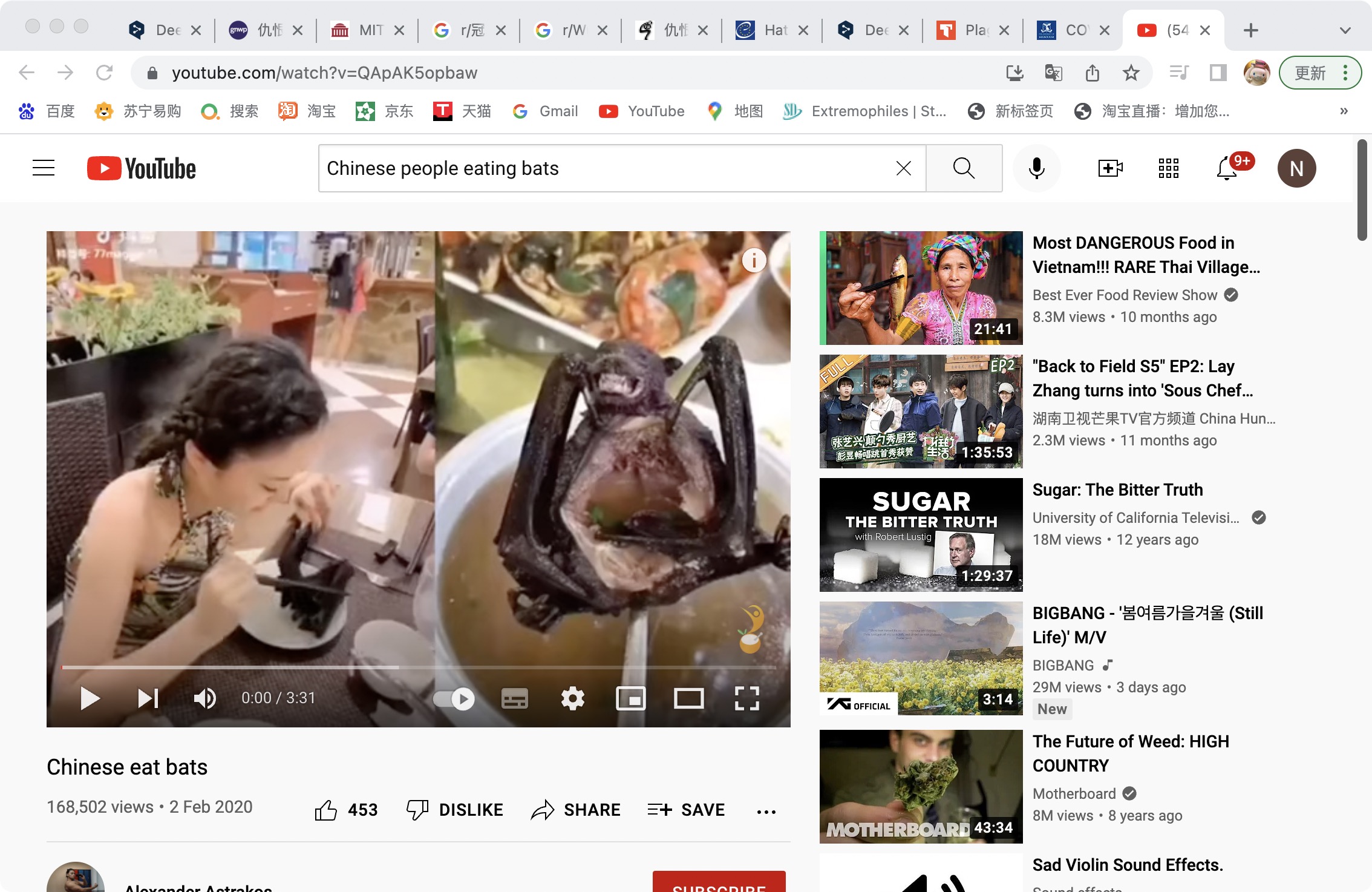

Figure 2: Chinese eat bats(Astrakos, 2020).

Since 2016, hate speech has often coincided with fake news. a study in December 2016 showed that of the articles about HATE SPEECH that month, 37 of them were associated with fake news. Excluding the coincidence of the same events occurring in both, the environmental factor linking them is likely to be the same online environment (Gollatz, Riedl & Pohlmann, 2018).

The rapid global spread of covid-19 in 2020 has largely caused public anxiety. Any major event that stirs the imagination has the potential to cause fake news (Nyilasy). The outbreak of this public health event has therefore made fake news for prevalent and has created challenges for the public. For example, in February 2020, at the beginning of the outbreak, a video with the title “Chinese eat bats” became popular on YouTube, which received 168,502 views and generated widespread discussion (Astrakos, 2020). As shown in Figure 2, the video shows a Chinese woman tasting a bat in front of the camera and saying in a gesture of enjoying the food, “It tastes just like chicken.” The video sparked a lot of anger and accusations online.

In fact, the video was filmed in 2016 and documents footage of the travel show and host with blogger Wang Mengyun tasting local food for viewers in Palau, a Western Pacific Island. According to Ms. Wang: “She was just trying to introduce the customs of the locals to the audience, oblivious to the fact that the bats might be carriers of the virus.” (BBC,2020). However, the video suddenly exploded in social media when cases emerged in Wuhan.

Hate speech on YouTube:

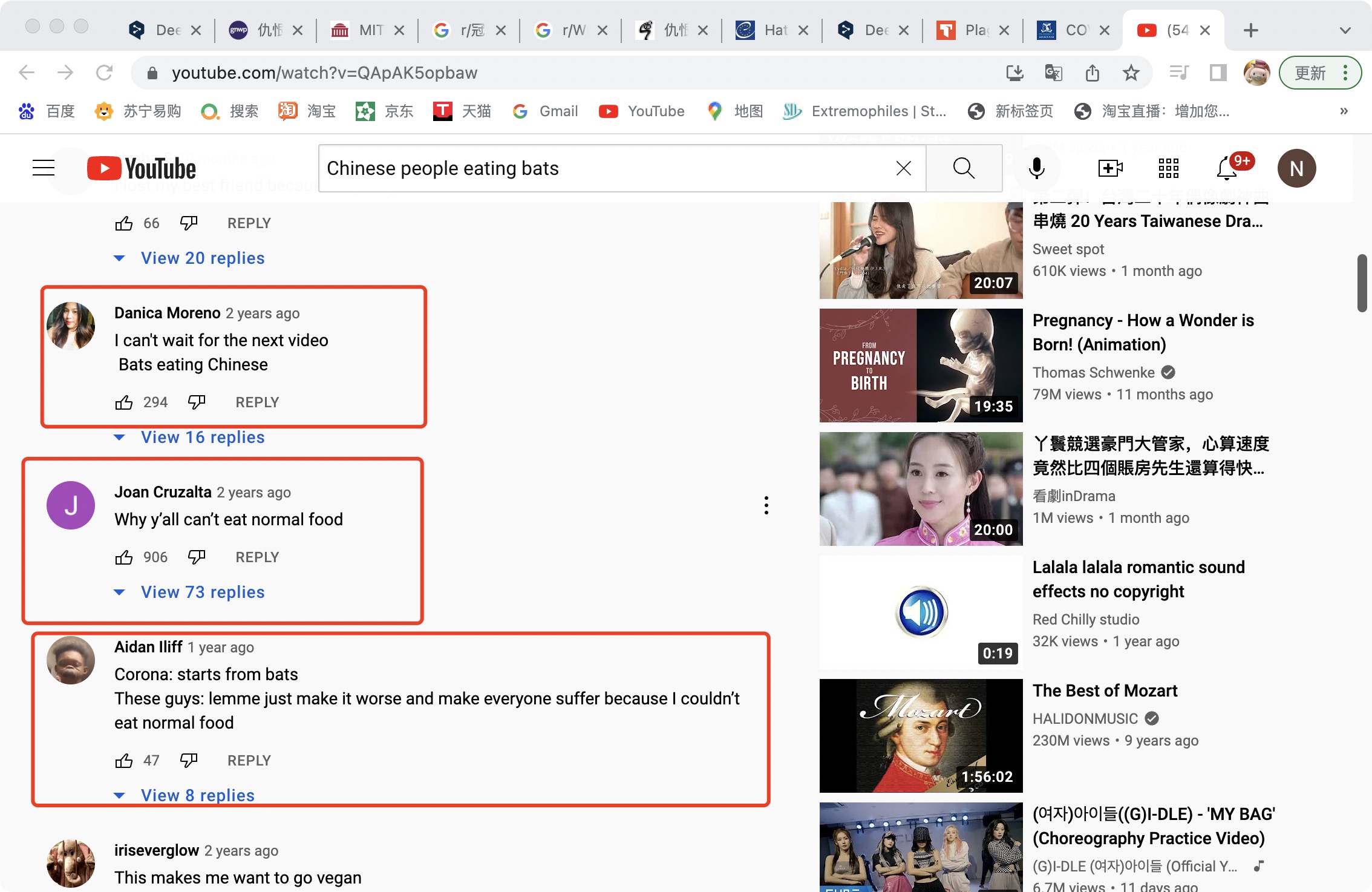

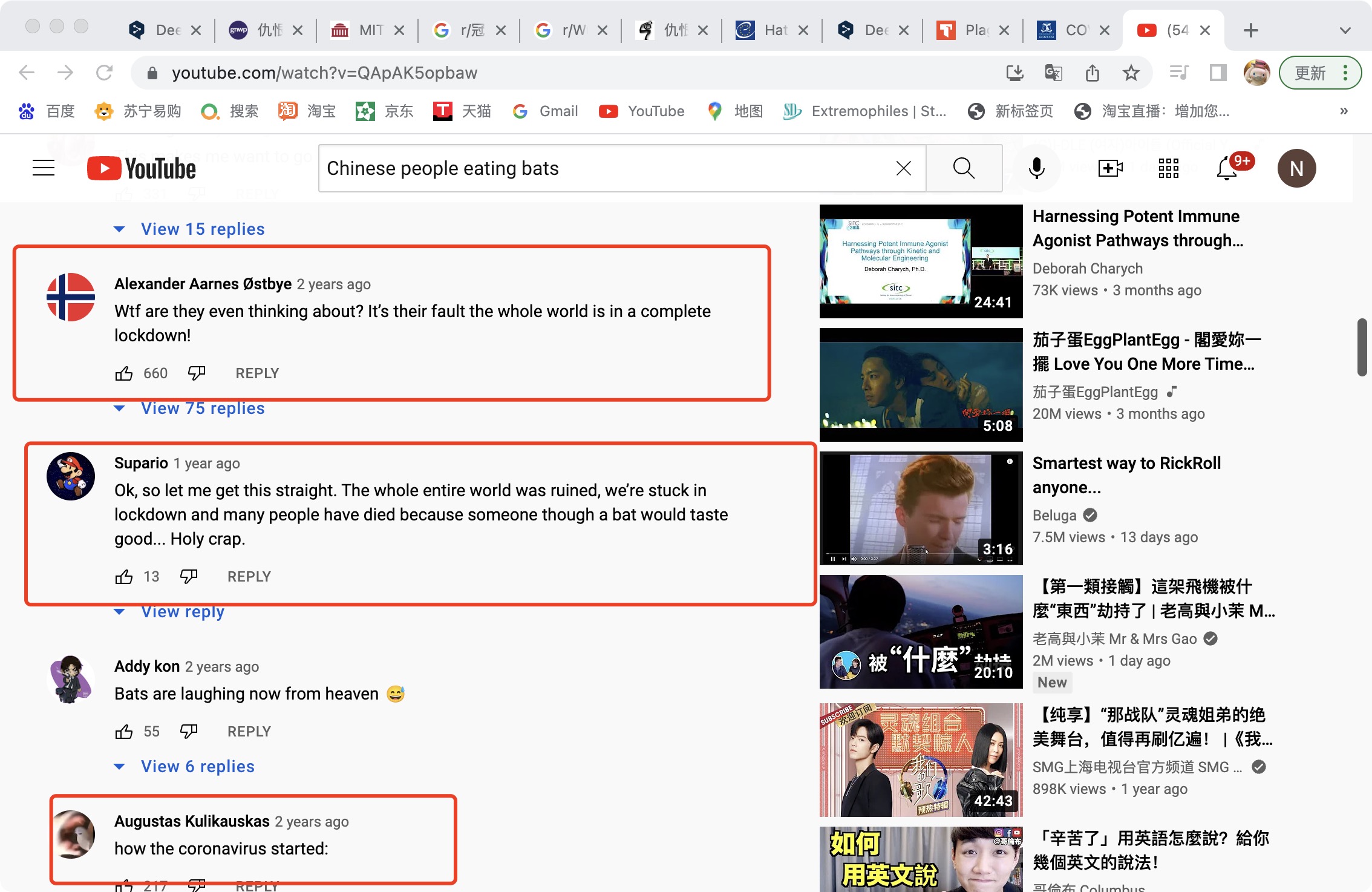

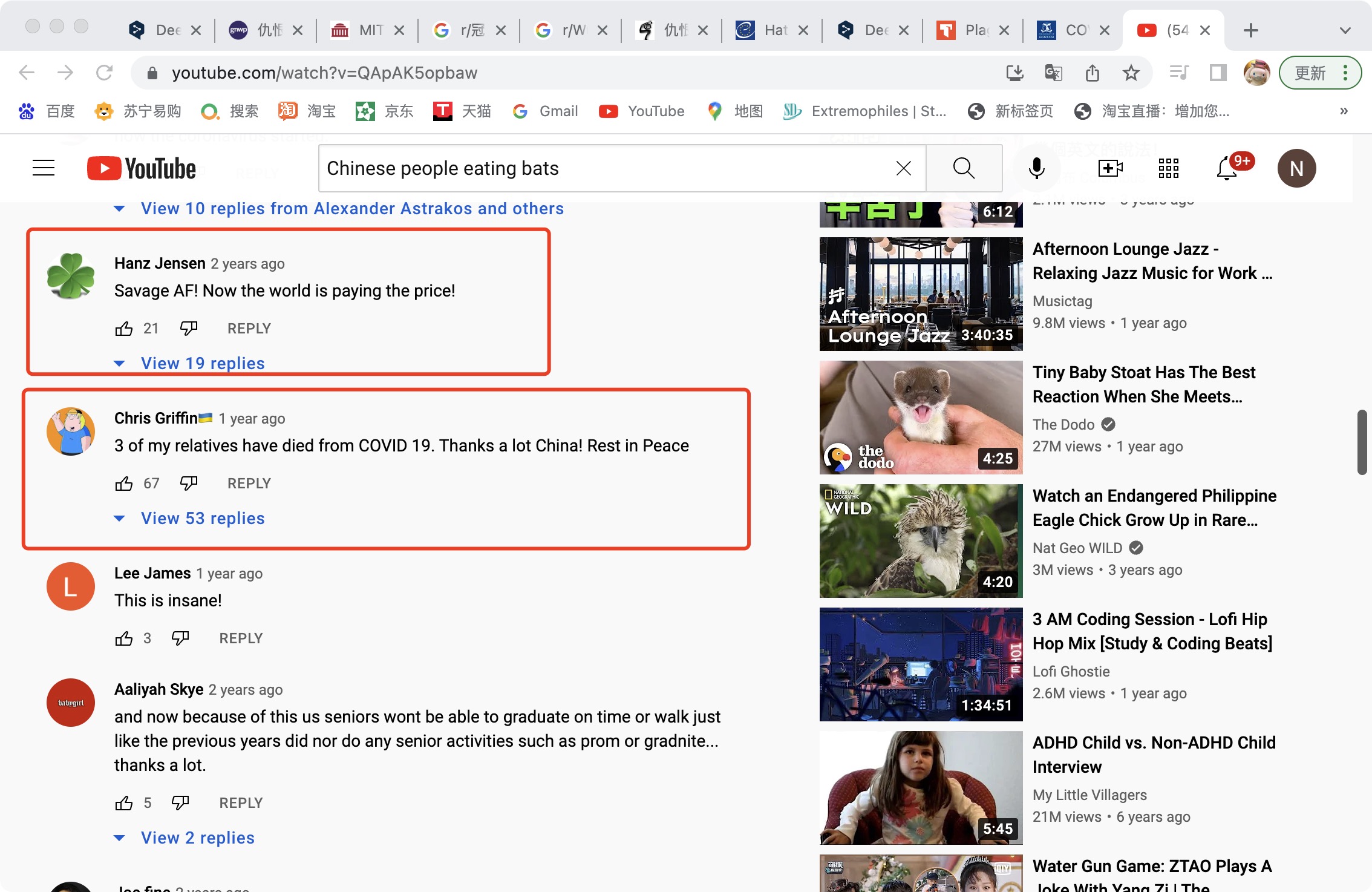

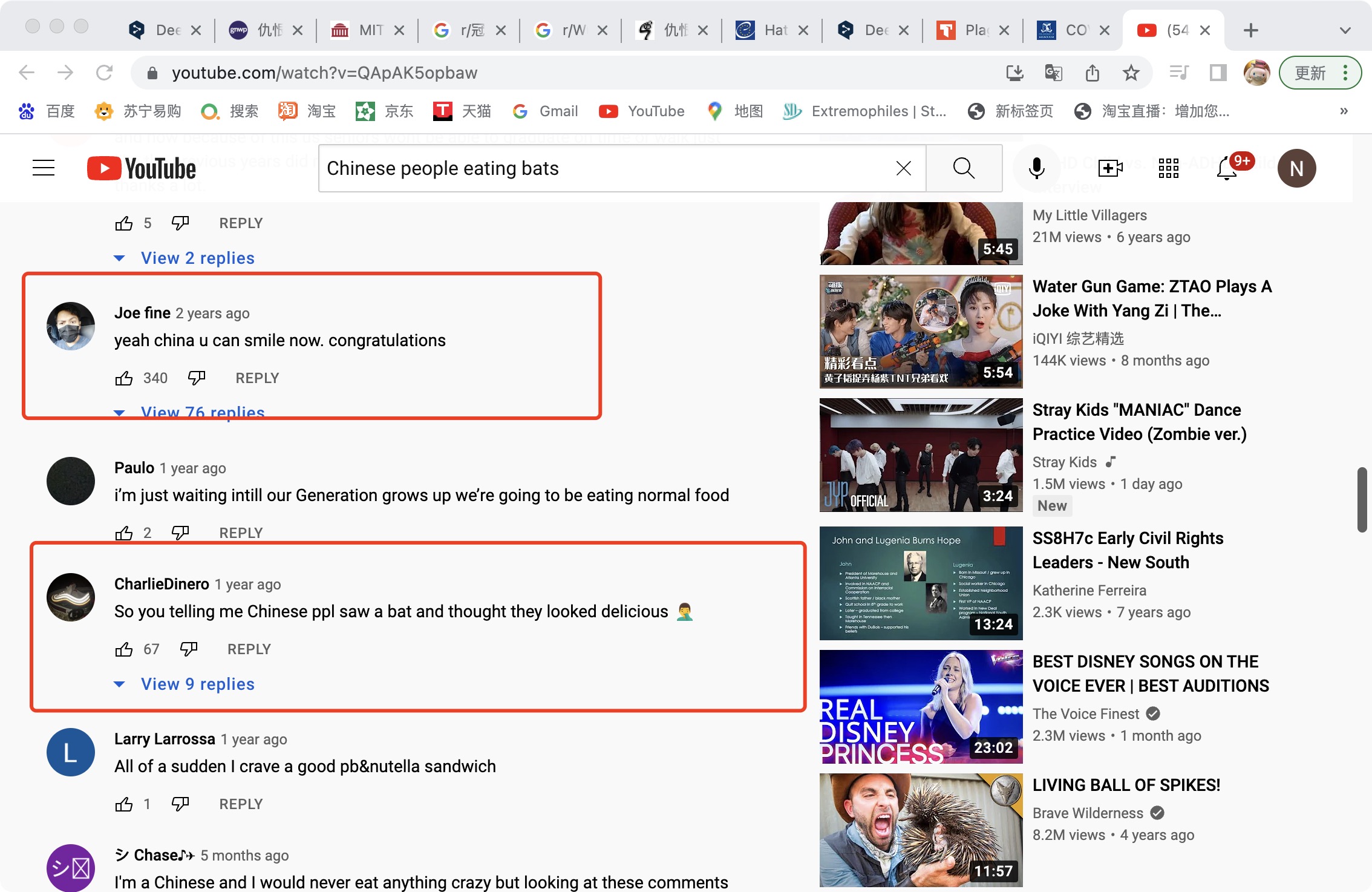

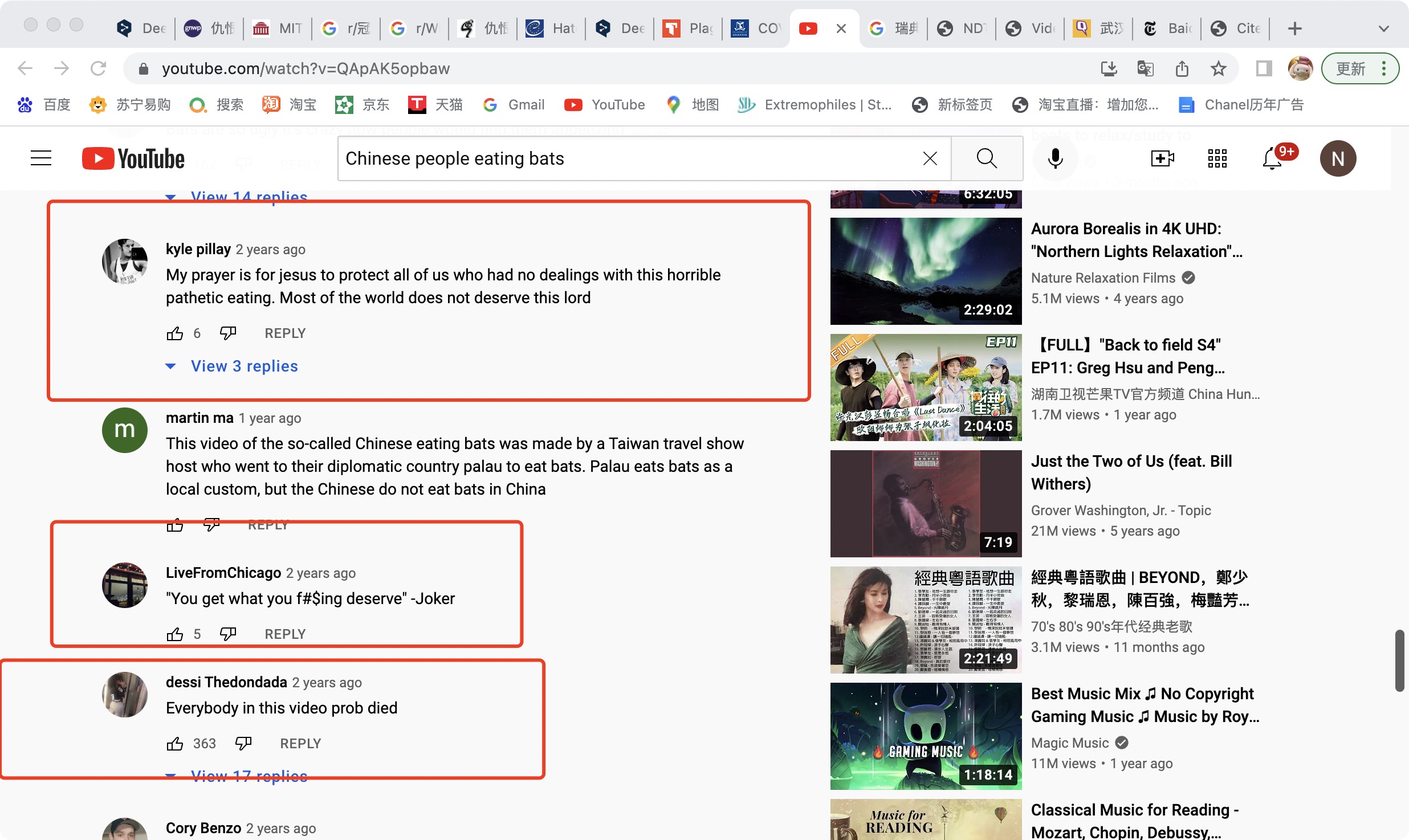

As shown in Figures 3 to 7, many users blamed the outbreak on the poor dietary practices of the Chinese and used offensive, demeaning, discriminatory and abusive language to attack the Chinese.

Figure 3: The screenshot of hate speech on YouTube

Figure 4: The screenshot of hate speech on YouTube

Figure 5: The screenshot of hate speech on YouTube

Figure 6: The screenshot of hate speech on YouTube

Figure 7: The screenshot of hate speech on YouTube

The impact of the Internet on racial identity and behavior has been a complex and ongoing area of research. (Matamoros-Fernández, 2017). Using the bat incident as an example, it is worth considering how hate speech reflects a governance blind spot in social platforms.

Firstly, inequality in access levels is one of the primary sources of racial inequality on the Internet (Matamoros-Fernández 2017, as cited in Hoffman & Novka 1998). This factor has been highlighted as inequality in digital literacy and skills and algorithmic accessibility (Matamoros-Fernández 2017, as cited in Hargittai, 2011). In that event, the data interface for Chinese users was subject to restrictions. The Great Firewall prevented users from accessing selected foreign websites and slowed down cross-border internet traffic (New York Times, 2015). Chinese users could not use social platforms such as YouTube, which prevented them from expressing their opinions and positions. In the face of statements such as “How the coronavirus started” and “It is their fault; the whole world is in a complete lockdown! The Chinese do not have the right to clarify the matter. In a situation where Chinese users do not have the right to speak and be informed, netizens have crusaded against the Chinese and attributed the entirety of the world-class disaster to China, which has become discursive bullying that degrades and insults China’s image.

Moreover, racism has been amplified based on unequal data interfaces. From a discursive perspective, the Internet is an opportunity to express national identity (Matamoros-Fernández 2017, as cited in Nakamura, 2002) and reproduce power relations (Matamoros-Fernández 2017, as cited in Kendall, 1998; McIlwain, 2016). As in Figure 5, statements such as “Savage AF! Now the world is playing the price!”, “Thanks a lot China!” and “Yeah China u can smile now… Congratulations.” The magnification of China’s alleged faults and the omission of the significant losses China has suffered in the epidemic reflect the racial consciousness of “white appropriation” (Matamoros-Fernández 2017, as cited in Moreton-Robinson 2015). The netizens perceive the world as the property of peoples other than China. The Chinese directly undermine their interests, thus ignoring or denying the heavy losses borne by the Chinese. The rhetoric on the platforms deepens the world’s long-established xenophobia. It maps China’s lesser control over international affairs and resources, a reproduction of its weaker international position than the West.

Besides, the networked nature of social media platforms allows hate speech to flourish in a decontextualized way across platforms (Matamoros-Fernández 2017, as cited in Nakamura, 2014). The decontextualized nature of hate speech is mainly responsible for users ignoring social context and social responsibility when posting their comments, focusing all their thinking on the events. This drives them to mask prejudice with humour and infinitely amplify racial slurs (Matamoros-Fernández 2017). As shown in Figure 6, “So you telling me Chinese ppl saw a bat and thought they looked delicious.” I cannot wait for the next video, Bats eating Chinese” (shown in Figure 3). Publics ignore the fact that the world is experiencing an unprecedented crisis and shirk their responsibility to maintain social and national stability in its midst, with users focusing on extracting critical information from the video, satirizing it, or making fun of it to attract more attention. However, in conjunction with YouTube’s sorting algorithm, the number of likes as an indicator influences where comments are displayed (Matamoros-Fernández 2017). In such a case, humorous comments will receive many likes and be topped in the YouTube comments section, and racist discourse is given relevance and legitimacy. It will have a more permanent presence on the Internet, with more significant negative consequences.

Fake news and Hate speech:

As shown in Figure 1, reviewing the seven types of fake news, the news in the case could be labelled as:

- Misleading Content, suggesting to the public that the Chinese have poor eating habits and largely contributed to the outbreak;

- Imposter Content, acting as a trigger for the story through a video that predates the outbreak;

- False Context, which was released during the epidemic and led everyone to attribute it to China.

These features all have a consistent pattern: linking everything that could have contributed to the outbreak to China, which reflects a strong bias. In addition to this, it is worth noting that the blogger who posted the video, Alexander Astrakos, is a former Swedish weightlifter, wrestler, and fitness model (YouTube). According to a survey, 85% of Swedes negatively view China in 2020 (Silver, Devlin & Huang, 2020). It can be seen that Alexander Astrakos is likely to be hostile to China and release false news. Therefore, we can conclude that fake news includes, to a large extent, prejudicial and discriminatory content against members of certain affiliated groups, which becomes a direct cause of fueling hate speech.

Criticism on Internet Culture and Governance:

In this case, it appears that political actors deliberately spread false information on the internet to intensify the antagonism and division between countries. In fact, the attributes of YouTube’s platform incited the expression of groups and channeled social sentiment, which led to the amplification of racial prejudice. Such an internet culture can be understood through the media ecology theory: the medium is a metaphor and has a mighty power of suggestion. Through metaphor, the medium can influence reality and even reconstruct the world (Postman, 1985). In this context, social media is no longer an ally of democracy but has become its enemy. Platforms will restrict or criticize their more easily discredited opponents according to their attributes or policies, responding with misleading and disinformation that confuses viewers about what is going on and makes misjudgments.

While many studies consider freedom of expression as an indispensable expression of freedom of thought and a tool for human development, political life and intellectual progress, hate speech is truly offensive (Terry, 2021). The original intent of the right to freedom of expression was to protect the right of citizens to express themselves and to allow them to construct an individual sense of community. It is worth considering that when the attributes of a platform are politically biased, the platform will evolve into a court of public opinion, when freedom of expression is likely to evolve into a tool of speech that serves the political situation. In such a situation, the public may appear to have the power to speak out, but their sense of self has been controlled, which means that freedom in a real sense disappears. It is thus clear that many platforms do not protect freedom of expression and even use this concept for political purposes. In this sense, hate speech should not be attributed to freedom of expression, and scholars should think more about the intricate media and information environment.

Conclusion:

In conclusion, this blog explores how fake news cause hate speech, thus revealing the politics of digital platforms. In such a situation, it is more important for platforms to introspect and introduce CDA (Critical Discourse Analysis) or other censorship departments to ensure their neutrality and objectivity.

Reference List:

Agata De Latour, Celina Del Felice, Menno Ettema, & No Hate Speech Movement. (2017). We can! : taking action against hate speech through counter and alternative narratives. Council Of Europe.

Astrakos, A. (n.d.). Chinese eat bats. Www.youtube.com. Retrieved April 9, 2022, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QApAK5opbaw&t=74s

Baidu and CloudFlare Boost Users Over China’s Great Firewall. (2015, September 14). The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/09/14/business/partnership-boosts-users-over-chinas-great-firewall.html

Barrera, O., Sergei Guriev, Henry, E., Zhuravskaya, E. V., & For, C. (2017). Facts, alternative facts and fact checking in times of post-truth politics. Centre For Economic Policy Research.

BBC Monitoring. (2020, January 30). China coronavirus: Misinformation spreads online. BBC News; BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/blogs-trending-51271037

Cambridge Dictionary. (2019, December 18). POST-TRUTH | definition in the Cambridge English Dictionary. Cambridge.org. https://dictionary.cambridge.org/us/dictionary/english/post-truth

Council of Europe. (2014). Hate speech and violence. European Commission against Racism and Intolerance (ECRI). https://www.coe.int/en/web/european-commission-against-racism-and-intolerance/hate-speech-and-violence

Flew, T. (2021). Regulating Platforms. Polity Press.

Germany: Removal of online hate speech in numbers – Kirsten Gollatz, Martin J Riedl and Jens Pohlmann. (2018, August 23). Inforrm’s Blog. https://inforrm.org/2018/08/24/germany-removal-of-online-hate-speech-in-numbers-kirsten-gollatz-martin-j-riedl-and-jens-pohlmann/

Higdon, N. (2020). The anatomy of fake news : a critical news literacy education. University Of California Press.

How Has the Internet Affected Freedom of Speech? (n.d.). FutureLearn. https://www.futurelearn.com/info/courses/global-citizenship/0/steps/121650

Keyes, R. (2004). The post-truth era : dishonesty and deception in contemporary life. St. Martin’s Press.

Matamoros-Fernández, A. (2017). Platformed racism: the mediation and circulation of an Australian race-based controversy on Twitter, Facebook and YouTube. Information, Communication & Society, 20(6), 930–946. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118x.2017.1293130

Post-Truth Politics, the Fifth Estate and the Securitization of Fake News | Global Policy Journal. (n.d.). Www.globalpolicyjournal.com. https://www.globalpolicyjournal.com/blog/07/06/2017/post-truth-politics-fifth-estate-and-securitization-fake-news

Postman, N. (2006). Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business. Penguin Books.

Robinson, S. (2020, May 13). Fake News in the Age of COVID-19. Faculty of Business and Economics. https://fbe.unimelb.edu.au/newsroom/fake-news-in-the-age-of-covid-19

Silver, L., Devlin, K., & Huang, C. (2020, October 6). Unfavorable Views of China Reach Historic Highs in Many Countries. Australian Human Rights Institute. https://www.humanrights.unsw.edu.au/news/unfavorable-views-china-reach-historic-highs-many-countries