Introduction:

Electronic technology has rapid developing which promoted the diversification of the network environment. As substantial Internet users has increased significantly, cultural, and digital literacy differences have also increased. As well as the anonymity and “low threshold” operability on social media, these discriminatory and controversial remarks will be quickly attracted and widely spread to audiences and incite users’ emotions thereby expand the influence of hate speech. As a result, hate speech a very serious and common online phenomenon. Hate speech is mainly based on differences and ideological conflicts of race, ethnicity, religion and political religion, in addition to stereotyped prejudice including appearance, race, gender and sexual orientation (eSafety.gov.au).

Hate Speech in Online

Image via: Yui Mok/PA

The common phenomenon of Online hate speech is defamation/metaphors behaviour to other people, threats of violence, and the creation of hate-related images and GIFs, to generate widespread attention and discussion on public forum platforms (Laub 2019). Among them, defamation/metaphors are more common, using insulting words to attack, derogate other people’s appearance, identity, sexual orientation, race, and nationality, etc (Terry 2021). Media platforms have vague rules for determining discriminatory comments, fuelling the rampant racism and sexist remarks. When it can be said that the platform cannot make a clear judgment in time for most “controversial content”, this is caused by the lack of understanding of the image of minority/marginal groups (Matatoros-Fernandez, 2017). Platforms do not take seriously the serious consequences of these cultural differences, but the breadth and effectiveness of social media dissemination has deepened the range and frequency of interactions between people and created a development environment for the growth of online hate speech. The direct result of the online environment full of hate cases is to intensify the conflicts between races, nationalities, and genders in the society, intensify hatred and hostility between people, and easily intensify the contradictions and cause social unrest and extreme events (Flew 2021). At the same time, for the victims of hate speech and online abuse, prejudice, and discrimination lead to them that accept greatly damage their self-esteem and lose their sense of self/social identity, resulting in self-loathing (Velásquez 2021). Users highly pursue freedom of thought on the Internet as a result they cannot grasp the boundaries of freedom of speech very well. The substantial of discriminatory remarks have been published on media platforms in the form of humour and ridicule. According to statistics, 23% of adult Australians believe that people should be free to say what they want online. This group is predominantly heterosexual, male from non-Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (Aboriginal) and Culturally and Linguistically Diverse (CALD) backgrounds, aged 30-40 (eSafety.gov. au).

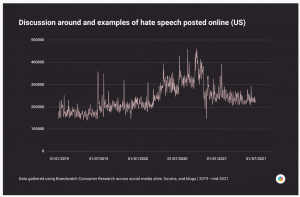

Covid-19 caused the flood of hate speech

Coronavirus disease pandemic has exacerbated users’ “disgust sensitivity” and xenophobia psychology, and between the two have increase positive correlation. Its epidemic has exacerbated people’s fear and anxiety about life, negative emotions lead to perpetrators of online hate speech may be in the same ill-health and accompanying trauma as their victims. And then, they will vent their anxiety about reality online by attacking others (Baggs 2021). UK youth charity Ditch the Label posted 50.1 million discussions or examples of racist hate speech in a study of 263 million social media conversations in the UK and US between 2019 and mid-2021, compared to pre-pandemic up 20%. (Ditch the Label 2021). Virus caused by disease contributes to the development of hate culture. More and more people are willing to find groups with the same cultural attributes as themselves on the Internet and establish a sense of cultural identity between groups. As such, minorities make up the vast majority of victims of online hate speech. In addition, the outbreak of the new crown epidemic in recent years has caused hate speech about people infected with the virus to begin to ferment on the Internet, and it has spread widely. Public discussions about online hate speech increased by 38%, and online anti-Asian hate speech significant increased by 1662% (Ditch the Label 2021).

Fight 1: the graph source from the data study results from a collaboration between Brandwatch and Ditch the Label. It is about the statistics released by hate speech in online social media sites, Forums, and blogs from the end of 2019 to mid 2021 after the outbreak of the new crown in the United States. It shows a significant rise in hate speech data since March 2020.

Virus-infected people have also become the main target of hate speech as a marginalized group in society. Coronavirus is highly transmissible and has spread widely around the world, posing a serious health threat. At the same time, the implementation of social distance and related lockdown policies has a huge impact on the economy and society, causing people to have negative emotions such as depression, anxiety, and sadness. And this kind of emotion has been converted into hatred by some Internet users, who published hate speeches about people infected with the virus. Virus-infected people suffer great blows and insults mentally while suffering the infestation of the disease physically. The pandemic has sparked more hate speech based on racial hatred and racism on social media that has fuelled a culture-clash movement to protect like-identity groups and bring them closer together (Milmo 2021).

Racist hate speech on Covid-19

Image via David Ryder/Getty Images

This image shows the “We Are Not Silence” rally, a protest march against anti-Asian hatred and prejudice. It took place in the Chinatown-International District in Seattle, USA. Demonstrators held signs of “Hate has no place” and “Racism is a virus” to demonstrate.Covid-19 has brought economic, political, cultural, and other pressures to society and tested its ability to respond to emergencies. The common response to the difficulties of the disease is to transfer hatred. These hatreds have deepened long-standing stereotypes about Asian and are quickly transformed into hateful topics fermenting on social media.

Fight 2: The graph from UNESDOC Digital library that data source from The Migration Unit of the IDB based on Citibeats data.

It shows about the number of tweets about bias against immigrant groups around February 2020. For the graph shows that prejudice against the immigrant group has risen by 70% and is on a long-term upward trend.

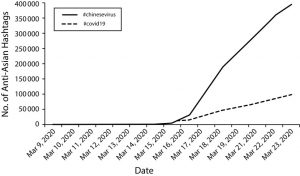

At the outbreak beginning of Covid-19 in 2020, former US President Donald Trump referred to covid-19 as the Chinesevirus and made inflammatory remarks that the virus originated in China when he spoke about the coronavirus. The racist hashtags “#Kungflu, #chinesevirus and #communistvirus were subsequently used in twitter, and all received a lot of discussion and traffic. Relevant statistics show 69,470 tweets between January 2020 and March 2020. and “#chinavirus” tweets with racially charged connotations (Hswen et, al 2020). The number of tweets with #chinavirus has surged since March 2020, with #covid19 hashtags among One-fifth of the entries were discussions of anti-Asian racism, and more than half of the hashtags with #chinesevirus (Hswen et, al 2020). And attacks don’t just happen online. Anti-Asian racist hate speech has led to frequent instances of real-world violence and stigma in Asian communities.

Fight 2: The graph shows the number of tweets about #chinesevirus with the #covid19 hashtags from March 9th to 23rd, 2020, and the number of usages of #chinesevirus has risen sharply since March 14th.

It shows the number of tweets about #chinesevirus with the #covid19 hashtags from March 9th to 23rd, 2020, and the number of usages of #chinesevirus has risen sharply since March 14th (Pérez 2021).

Voices about female hatred and gender antagonism

Since the start of Covid-19 epidemic, Phoebe Jameson has long been attacked by extreme rhetoric about body shame. Just because she posted on social media in March 2020 about commemorating International Women’s Day and posted a photo of her body front, there was a lot of talk about attacking her image, and it continues to this day”. “Phoebe Jameson said she receives a large number of offensive and abusive comments every day and that she is being abused online. The reason for these comments attacking Phoebe for not conforming to the current mainstream aesthetics is that she is too fat. In an interview with Phoebe Jameson, she said that she received hundreds of death threat messages every day. Those anonymous people described her image as ugly and said, “she needed to lose weight” or “she would die at 40”, “unworthy of love and good things” (Taylor 2020). When faced with online abuse at Phoebe, the advice and recommendation from everyone around her that was keeping off the internet. In fact, most online victims have been quit the Internet and delete their accounts after being subjected to substantial online insults. Even in the face of death threats, police are giving advice to stay away from social media and offline accounts rather than sanctioning users who post hate speech. Social media platform administrators don’t have a comprehensive view of online abuse, and they only penalize offending users in extreme cases. But usually, hate speech content is vaguely used to attack victims in metaphorical and obscure expressions, and it is more difficult to judge with current website censorship rules that are not comprehensive. In addition, most of the reviews on Phoebe are from “fake users” which further catalyses online abuse. Phoebe needs to block a large number of users who express hate speech every day. Since the platform is not comprehensive in terms of management and blocking of user rules and regulations, most anonymous netizens will not be punished, which makes this situation worse.

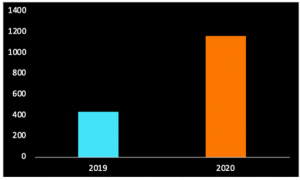

Fight 4: graph source from: UN Women

It shows the number of misogynistic Facebook posts published by UN Women in 2019 and 2020 targeting the South and South-East Asia region. There has been a significant increase in hate speech between these two years.

For the depth analysis, Phoebe’s experience of online abuse, it shows that these remarks had strong misogyny and gender-biased intentions, and their attacks on Phoebe stemmed from her not conforming to their ideal female image (women should stay slim and pay attention to demeanour etc. stereotypes). Covid-19 has seen a surge in discussion and interest in misogynistic topics on social media. Online spaces are enriched with a wealth of sexist, inaccurate, and dangerous rhetoric about women. “COVID-19 exposes ugly truths about women,” “Women are more at risk than men during COVID-19,” and “COVID-19. Highlights gender-biased laws against men.” is a trending topic discussion on Facebook and Twitter (UN Women 2020). Women and transgender people are the main victims of “this epidemic storm” that especially in Southeast Asia

Conclusion:

At present, the development of Covid-19 epidemic around the world is still developing rapidly, and the fermentation status of racist and sexist hate speech in the online environment is still not optimistic. Lockdown policies have exacerbated the amount of time people spend online, taking their real-life frustrations online to vent. The pursuit of extreme culturalism can quickly and easily build a sense of group identity, and online hate speech and interest in minorities have peaked under the impetus of the epidemic. Most users enjoy interacting, commenting, and sharing in forums about hatred of women and racism. Long-term online hate speech can easily turn into the probability of offline violent conflict and extreme events. Therefore, in the face of the current uneasy network environment, the platform needs to improve the supervision policy for online abuse and evaluate the online speech of users more comprehensively and intelligently. Although the platform still has doubts about users breaking “identity anonymity” and “the norms of freedom of speech on social media”, the relevant policies cannot be implemented. But the leaders of social media sites and governments are the best way to govern and regulate hate speech in the online environment. At the same time, social media users should improve their digital literacy and strengthen the psychological quality of online citizens to regulate online behaviour.

Reference List:

Baggs, M. (15 November 2021), Online hate speech rose 20% during pandemic: We’ve normalised it’, BBC News, https://www.bbc.com/news/newsbeat-59292509.

Baggs, M (8 February 2021), Online bullying: ‘I’ve blocked nearly 10,000 abusive accounts’ BBC News, https://www.bbc.com/news/newsbeat-55668872.

Ditch the Label (2021), Uncovered: Online Hate Speech in the Covid Era, Brandwatch https://www.brandwatch.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Uncovered_Online_Hate_Speech_DTLxBW.pdf

eSafety Commissioner (2020), Hate Speech Report https://www.esafety.gov.au/sites/default/files/2020-01/Hate%20speech-Report.pdf.

Flew, T. (2021) Regulating Platforms. Cambridge: Polity, pp. 91-96.

Hswen,Y., Xu, X., Hing, A, Hawkins, B. J, PhD, J S. Brownstein, S J. & Gee, G. C (2021), Association of “#covid19” Versus “#chinesevirus” With Anti-Asian Sentiments on Twitter: March 9–23, 2020, Am J Public Health. 111(5) P956–964. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2021.306154.

Laub,Z. (June 7, 2019), Hate Speech on Social Media: Global Comparisons, Council on Foreign Relations, Retrieved from: https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/hate-speech-social-media-global-comparisons.

Milmo,D. (19 Oct 2021), The guardian, ‘Nastier than ever’: have Covid lockdowns helped fuel online hate?, https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2021/oct/19/nastier-than-ever-covid-lockdowns-rise-online-hate.

Pérez, A, L. (2020), The “hate speech” policies of major platforms during the COVID-19 pandemic in UNESCO, [Graph] https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000377720_eng

UN Women, (2020), Social Media Monitoring on COVID-19 and Misogyny in Asia and the Pacific” Retrieved from: https://asiapacific.unwomen.org/sites/default/files/Field%20Office%20ESEAsia/Docs/Publications/2020/10/ap-wps-BRIEF-COVID-19-AND-ONLINE-MISOGYNY-HATE-SPEECH_FINAL.pdf. ”

Velásquez, N., Leahy, R., Restrepo, N.J (2021) Scientific Report, Online hate network spreads malicious COVID-19 content outside the control of individual social media platforms, Retrieved from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-021-89467-y.

Matatoros-Fernandez, A. (2017). Platformed racism: the mediation and circulation of an Australian race-based controversy on Twitter, Facebook and YouTube, Information, Communication & Society 20(6), pp. 930-946.