Introduction

With the rapid development of information technology and the emergence of a variety of Internet platforms, social media has increasingly become an indispensable part of people’s lives. However, the rise of new media has brought new problems, as traditional media fades away due to market squeeze, fragmented information begins to flood people’s lives. When reports without context and news elements become the main source of information, people’s inferences about situations, decisions regarding important matters, and perceptions of value are skewed to the extent that society becomes increasingly polarised in its thinking. This phenomenon is mainly related to the key concept of “filter bubble” which will be introduced in this blog post.

The concept of “filter bubble” was proposed in 2010 (Pariser, 2011), but the discussion about it has become noisier and noisier in the past two years. This is mainly due to several popular incidents in recent years that have set off discussions and criticism of social media. Events ranging from the surprise election of Donald Trump in 2016 US presidential election to the influential 2020 documentary The Social Dilemma (Orlowski, 2020) and the “Facebook Files” exposed by former Facebook employee Frances Haugen, are leading to a growing awareness of the existence of filter bubbles among social media users.

Social media is increasingly becoming more part of our lives, but what exactly should we deal with it? A proper understanding of social media and stepping out of the filter bubble can help us stay awake and maintain independent judgement in this digital age.

The Formation of Filter Bubbles Is Inevitable in the Era of the Internet

If you have been following the 2016 US presidential election, then I believe you are probably like many people who still find it hard to forget how shocked they felt by the election results.

To explain in simple terms, the concept of a “social bubble” is machine learning generated by users as they use online sites, driving the machine to recommend more content to users that reinforces existing beliefs. (Flew, 2021) “Predictive engines” are now more commonly referred to as “algorithms” and are present in all aspects of our internet lives. Pariser said in 2011 that Google uses 57 signals to tailor your search results, but by 2016, this number increased to over 200 according to this search giant itself. (Baer, 2016)

Users’ interest information and usage habits are probably the most valuable assets in this mobile Internet era. And in the smartphones that almost everyone uses on a daily basis, there are built-in features for developers to use as advertising identifiers. In iOS, this feature is called IDFA (Identifier for Advertising), while in Android it is called GAID (Google Advertising ID). (Newman, 2019) If you ever have the experience that, you are searching for a product on a search engine, and the product pops up through a push notification by a shopping platform just in the very next second – there would be no doubt that these ad identifiers did the trick.

From the perspective of some specific application scenarios, the recommendation algorithm does bring some positive browsing experiences to Internet users. However, when recommendation algorithms are applied to social media, social bubbles are formed.

Under Lack of Regulation, Filter Bubbles Tear Community Apart

Social media is a very new existence. Although its name is “media”, unlike traditional media, the platform itself does not produce news content. This has led to a fundamental change in the pattern of how people receive information. (Andrejevic, 2019)

George Washington University media-studies assistant professor Nikki Usher Layser said in an interview with the media that the biggest difference between obtaining information through social media and traditional media is “autonomous decision-making”. (Baer, 2016) Layser says that while traditional media are not perfect, at least they can be contextually aware and provide a contrasting narrative. But on social platforms, if users only read and interact with the posts on their own feeds, it will be difficult to get information outside of their filter bubbles.

With the rise of social media, more and more traditional media have disappeared, and many small-scale local newspapers have been replaced by Facebook groups. However, platforms such as Facebook and Twitter are reluctant to see themselves as publishers or to take responsibility for the content circulating on their platforms. (Andrejevic, 2019) The logic behind this phenomenon is actually not difficult to understand – it is the business model that drives it. According to Lewis (2018), the business model of social media is mainly related to two key metrics, namely ‘stickiness’ (how long users stay) and ‘engagement’ (users producing content and interacting). The higher these two numbers are, the more personal information the platform can collect and the more frequently it can show ads to users.

This coincides with the files that were exposed by former Facebook product manager Frances Haugen in 2021. Leaked internal documents show that Facebook users became noticeably angrier after the Facebook algorithm was changed in 2018. Facebook insiders suggested revisions to the algorithms, but Facebook CEO Zuckerberg rebuffed their suggestions, citing concerns that the revisions would lead to fewer interaction data. (Hagey & Horwitz, 2021)

Yes, simply put, in order to obtain more advertising revenue and data on user behaviour, Zuckerberg deliberately made the algorithm to guide users to argue in Facebook’s comments section.

The Difficulties to Avoid Filter Bubbles Are Caused by Human Nature

Now that we understand the causes and harms of filter bubbles, here is the not-so-good news: filter bubbles can be hard to avoid for most people. There are a variety of reasons for this, but one of the biggest is that most people don’t see social media as a traditional source of news. In addition to obtaining information, social media is also a vehicle for many varied online subcultures. For example, a study that recorded and analysed texts and patterns related to entertainment and technology topics on Weibo found that groups of users with diverse sources were more likely to spread technology content, while users in entertainment communities were more likely to spread misinformation. In addition, users within the social bubble follow a very centralised source of information and rarely receive information from other sources, which also leads to information polarisation. (Min, Jiang, Jin, Li, & Jin, 2019)

Another reason why filter bubbles are hard to avoid is the political reality. For some politicians, improving the filter bubble does not help their electoral strategy, but rather exacerbates the flow of disinformation to their advantage. (Andrejevic, 2019) For example, a conservative businessman told The New York Times that, in his world, he takes right-wing conspiracy theories as just a form of entertainment: “I just like the satisfaction … It’s like a hockey game. Everyone’s got their goons. Their goons are pushing our guys around, and it’s great to see our goons push back.” (Tavernise, 2016) It is not only in the political sphere that internet users are not responsible for their own words and actions, but just for having “fun”.

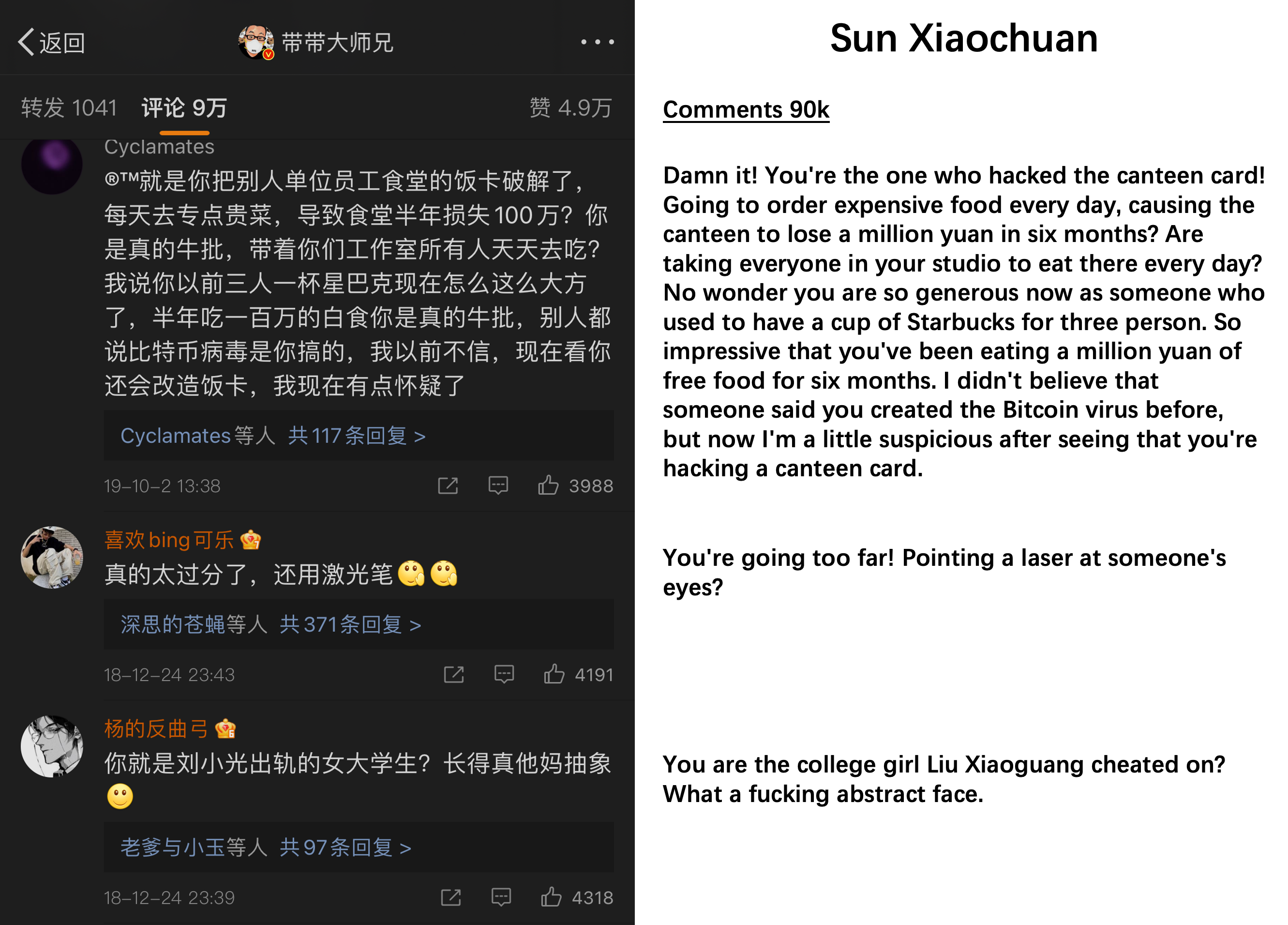

Another well-known example includes the fan community of Chinese streamer Sun Xiaochuan – whose fans are not really supporters and followers but simply use him as a cultural meme to look for fun. The way Sun Xiaochuan’s “fan community” entertains themselves is to put charges on him that have nothing to do with him. Including falsely claiming that he is a supporter of Japanese militarism and visited the Yasukuni Shrine, maliciously reporting foreign games on Tencent’s game store and causing them to be taken down, pointing a laser pointer in a singer’s eyes while watching his concert, etc. In general, the aim is to associate some controversial events with him to demean both sides. Of course, these actions, which are fun in the eyes of some, will create misunderstandings among other Internet users. And the difference in information and recognition between the two sides makes the views begin to diverge. Drawing on the simple model in this example, we can get a glimpse of how filter bubbles are formed.

All in all, whether it is platforms such as Facebook, relevant stakeholders such as politicians, or even most Internet users themselves, they are all great resistances to the improvement of filter bubbles.

Being on The Internet, Crossing Divides Matters

In the digital age, information has never travelled from person to person at such a rapid pace as it does today, and human life has never been easier – the thing which also transmits at such a rapid pace, of course, is disinformation.

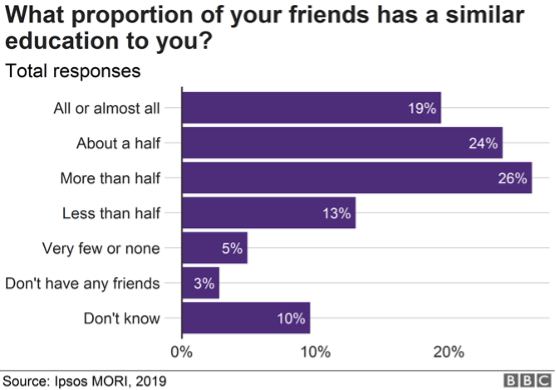

A 2018 poll conducted in 27 countries showed that 65% of people believed other people were living in their own internet bubble, but only 34% believed they were living in these bubbles themselves. (Ipsos Public Affairs, 2018) The data clearly indicates that a significant number of internet users do not realise that they live in a social bubble. Admittedly, everyone is actually under a lot of stress in real life, and it is understandable that many people go online just to relax and only communicating within their social bubble is a great way to get a sense of accomplishment and satisfaction. However, being in a social bubble for a long time not only makes one easier to develop wrong perceptions and thus make wrong decisions but also encounters “big data discriminatory pricing” that even causes financial losses. (Liu, Long, Xie, Liang, Wang, 2021)

Here are some measures we can try to avoid getting stuck in a filter bubble:

- Broadening the scope of interests and concern information in multiple fields (Min, Jiang, Jin, Li, & Jin, 2019)

- In addition to very large accounts, it is also important to focus on smaller accounts in order to make one’s sources as decentralised as possible (Min, Jiang, Jin, Li, & Jin, 2019)

- Talk regularly with different people who hold different positions, to understand and reflect on different perspectives

- Develop the habits of accessing news through traditional media, understanding the context rather than relying solely on fragmented information to make judgements

Conclusion

In conclusion, there is no doubt that the formation of filter bubbles is an inevitable part of the Internet era, and that their negative effects are widespread and profound. All parties have played a role in the effort to break the filter bubbles, but at the same time resistance has been encountered from parties including social media platforms themselves, political forces, and users of online platforms user communities. However, in any case, while people are entertaining and relaxing through the Internet, they should always be aware of the existence of filter bubbles and put in place defences against the negative effects it possibly brings. Research and data indicate that a large proportion of people are unaware of the existence of filter bubbles, and therefore unaware that they are in these bubbles themselves. Therefore, people should take specific measures to identify and get rid of these filter bubbles, so as to avoid making wrong judgments and plans due to unreliable information channels, and even causing financial losses. In addition, in addition to the efforts of users themselves, regulators and platforms should also take action by formulating and implementing specific measures to address the social problems created by filter bubbles, in order to protect those “vulnerable” in the non-traditional sense in this new information age.

Reference List

Andrejevic, M. (2019). Automated Media. Milton: Routledge.

Baer, D. (2016). The ‘Filter Bubble’ Explains Why Trump Won and You Didn’t See It Coming. Retrieved from https://www.thecut.com/2016/11/how-facebook-and-the-filter-bubble-pushed-trump-to-victory.html

Flew, T. (2021). Regulating platforms. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

Hagey, K. & Horwitz, J. (2021). Facebook Tried to Make Its Platform a Healthier Place. It Got Angrier Instead. Retrieved from https://www.wsj.com/articles/facebook-algorithm-change-zuckerberg-11631654215?reflink=desktopwebshare_permalink

Ipsos Public Affairs. (2018). Fake news, filter bubbles and post-truth are other people’s problems… Retrieved from https://www.ipsos.com/en-uk/fake-news-filter-bubbles-and-post-truth-are-other-peoples-problems

Lewis, P. (2018). ‘Fiction is outperforming reality’: how YouTube’s algorithm distorts truth. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2018/feb/02/how-youtubes-algorithm-distorts-truth

Liu, W., Long, S., Xie, D., Liang, Y., & Wang, J. (2021). How to govern the big data discriminatory pricing behavior in the platform service supply chain?An examination with a three-party evolutionary game model. International Journal of Production Economics, 231, 107910–. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2020.107910

Min, Y., Jiang, T., Jin, C., Li, Q., & Jin, X. (2019). Endogenetic structure of filter bubble in social networks. Royal Society Open Science, 6(11), 190868–190868. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.190868

Newman, L.H. (2019). A Simple Way to Make It Harder for Mobile Ads to Track You. Retrieved from https://www.wired.com/story/ad-id-ios-android-tracking/

Orlowski, J. (Director). (2020). The Social Dilemma [Film]. Exposure Labs, Argent Pictures & The Space Program.

Pariser, E. (2011). The filter bubble : what the Internet is hiding from you. London: Viking.

Sun, X. (2018). Just for fun, don’t take it seriously. https://weibo.com/3176010690/H8Ktq8f8H

Tavernise, Sabrina. 2016. “As Fake News Spreads Lies, More Readers Shrug at the Truth.” The New York Times, December 6, 2016. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/12/06/us/fake-news-partisan-republican-democrat.html