Introduction

Users are unavoidably disturbed by fake news, hate speech and terrorism on platforms while receiving convenient communication and utilising advanced technology with the development of the Internet. Hence, online platforms have moderated their online content to protect users’ and their own economic interests. Content moderation can be defined as the interventions that platforms adopt to review and assess unacceptable content and behaviours in their opinions (Gillespie et al., 2020). More and more scholars and users have realised that content moderation is a quite powerful control mechanism during its actual execution. Some large social media, such as Facebook and Twitter, have developed content moderation systems influencing billions of people worldwide and shaped the rules of online expression.

However, who is responsible for establishing standards for the mechanisms of content moderation of online platforms? This question remains unanswered due to confidentiality and non-transparency of content moderation policies of online platforms. The phenomenon has raised concerns about the democratic legitimacy of moderation mechanisms. The current content moderation mechanism developed by private companies in an opaque manner is not reasonable enough. They lack corresponding accountability systems and oversight. Political groups involved should intervene in establishing content moderation rules and jointly supervise online platforms with the firms.

Facebook’s content moderation mechanism is an appropriate example. First, the blog will focalise a well-known dispute about Facebook content moderation in 2016 to demonstrate the current unreasonable mechanism adopted by the mainstream social media platforms. Secondly, it will review the process and principles of Facebook’s team members defining the manual moderation standard and discuss whether the standard embodies minor Silicon Valley elites’ ideologies. Next, this blog will demonstrate the current mechanism requires transparency and an accountability system. Finally, this blog will discuss how Facebook’s AI-based content moderation algorithm has exacerbated the unreasonable and non-transparent nature of the moderation process.

Child Pornography?

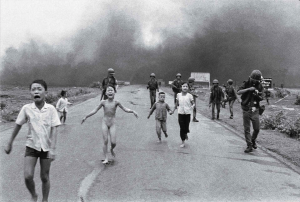

Retrieved from: https://aboutphotography.blog/blog/the-terror-of-war-nick-uts-napalm-girl-1972

In 2016, a Norwegian journalist posted a photo on his Facebook page reflecting the atrocities of the Vietnam War. This photo is of Kim Phúc, a nine-year-old Vietnamese girl. She is running on the road burned by petrol bombs, naked, with terrible burn marks on her skin, with an expression of pain and fear. The photo shocked the world and was named ‘The Terror of War’. In 1973, under enormous social pressure, it was published in newspapers and won a Pulitzer Prize. However, in 2016, ironically, the photo was removed thousands of times by the site for violating Facebook’s terms of use. Because of the journalist’s insistence, the removal of the picture triggered a widespread public protest. In the end, Facebook compromised and issued a statement, which nonetheless called the photo “child pornography” and said it was being removed to protect children.

This example explains Facebook’s moderation standard probably is simplified polarising judgment. The censors noticed Kim Phúc’s naked skin rather than her burned skin, and much less to the anti-war significance that the skin reflected. This speculation was confirmed by the subsequent statement. The question arises here, who defined the photograph as child pornography?

The US law does not require Facebook to moderate contents on the platform. Most technology companies, including Facebook, enjoy legal immunity for the content posted by users on their services under a 1996 federal law. In 2005, Facebook began to actively dispose of hate speech and pornographic contents after an internal corporate debate. In 2008, the company started to expand internationally. Dave Willner complied a 15,000-word rules manual, which remains to be the basis of many content moderation standards of Facebook. Jud Hoffman, a global policy manager of Facebook at the time, said the rules were influenced by the Harm Principle articulated by John Stuart Mill (Angwin & Grassegger, 2017). However, it was not until 2018 that Facebook explained its content moderation process in more detail and released a slightly abridged version of its internal guidelines for reviewers.

A World of Private Law

Retrieved from: https://www.apc.org/fr/node/35064

It is evident that Facebook’s regulations of censorship have been imposed by the company’s management, the Silicon Valley elites. David Kaye, a law professor and the former United Nations Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression, described his experience as an “invited observer” to a Facebook conference on content policy. He noted that the employees around him were “mostly young, dressed down, smart, focused” and ” seemingly drawn from elite schools and government institutions in the West”. He observed that they asked many questions and tried getting things done. However, billions of people who were never involved in decision-making have been affected by their decisions (Galantino, 2021, p.53).

One of the cornerstones of democracy is the separation of powers. It means that the functions of legislation, assessing legality, law enforcement and imposing penalties are entrusted to different institutions, operating independently and monitoring each other (Gillespie et al., 2020). However, the existing online content moderation systems obviously violate the system. Facebook’s rules constitute its world of private law, from legislation to enforcement, totally conducted by the head office and some outsourcing companies. The phenomenon allows them to impose their values on all users.

As Roberts (2018) says, when we use commoditized logic to explain Facebook’s actions in the Vietnam War photo incident, some seemingly absurd behavior seems plausible. Every photo uploaded on social media is treated as a potential revenue-producing product. And it circulates in order to provide the platform with traffic, engagement, and advertising revenue. The reviewers categorised those photos as commodities. This important anti-war photo was categorised simply on the basis of its sexual value and was judged to be inappropriate for the platform; as a result, it was removed. The consequence reflects the company’s moderation principles established for profits rather than on responsibilities of managing public discourse. Unfortunately, common users find it is difficult to resist the rules, or worse, they will be disciplined and lose perspective.

The inveterate platform racism on Facebook has also been criticized (Matamoros-Fernández, 2017). A large number of minorities have criticised Facebook’s moderation mechanism for not protecting them on social media, but for indulging attacks on them. Actually, it is the result of Silicon Valley’s libertarian ethos. Between individualistic and collectivistic freedom, Facebook has always privileged the former, that is, supported unrestricted freedom of expression (Gillespie, 2018). Consequently, offensive or biased statements could exist on the platform without censorship. For example, about the hate speech policy, Facebook “allows humour, satire, or social commentary related to these topics” (Facebook, n.d.). Hence, plenty of racist memes spread on the platform to attack women, Blacks, indigenous people, etc. Most minorities were offended and hurt while browsing Facebook.

Rules Operating in the Shadows

Few social media platforms are willing to disclose details of content moderation. In their opinions, full disclosure of the policies would cause malicious users to attempt to manipulate rules or probably give an advantage to commercial competitors by disclosing practices or processes they consider to be secrets. On the other hand, social media platforms feel shame on acknowledging their need for large-scale and industrialized content moderation. Complete disclosure of content moderation mechanisms could break the myth of the freedom of speech on the platform and damage the company’s reputation (Roberts, 2019). With these factors in mind, the platforms have deliberately blurred moderation mechanisms and rendered them non-transparent and ambiguous. There is little publicly available data indicating the amount and types of contents deleted each day. External researchers and government regulators tend to rely on user-dictated experiences to guess the mechanisms. Therefore, it is difficult to regulate the platforms.

Typically, web platforms outsource content moderation to specialised companies to identify and remove online content that is considered to conflict with their Terms of Service. Most of the censors are workers and freelancers from developing countries who may not have accepted professional training beforehand or are entirely unaware of the nature of their work. They have to process tens of thousands of pieces of data every day and decide rigidly in a short time according to the standards provided by the firm. Many studies have proved it to be a form of labour exploitation (Roberts, 2019).

But more importantly, content moderators are often required to sign non-disclosure agreements. They cannot reveal their job contents or decision criteria, which causes content moderation to become an almost obscure and authoritarian tool. Imagine that you don’t know who has reviewed your uploads and why they’ve been removed. No idea who to hold accountable if legitimate content is removed. You can only be forced to accept the result of account freezing or dynamic deletion. And this is the norm that social media users face when using the platform. A study shows that most social media users express considerable concern about moderators and moderation processes, and that concern breeds conspiracy theories (Suzor et al., 2019). Civil society speculates, for instance, that Facebook deletes ‘The Terror of War’ since censors are radical supporters of wars or the picture threatens the US government’s interests, rather than simply removing child pornography.

Retrieved from: https://www.theverge.com/2019/2/25/18229714/cognizant-facebook-content-moderator-interviews-trauma-working-conditions-arizona

Are the technologies the savior of the moderation mechanism?

Manual moderation is not enough for those with colossal traffic, and most platforms have introduced algorithmic content moderation mechanisms. Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg cited “artificial intelligence” dozens of times in his 2018 congressional testimony as a future solution to Facebook’s current political problems. Can these technologies and algorithms solve the problem of democratic norms and the opacity of moderation mechanisms? The answer seems unsatisfactory.

The most apparent flaw in content moderation with the use of the algorithm is the abuse of polarising judgment. The algorithm only judges whether the content conforms to the regulations based on the similarity analysis. ‘The Terror of War’ may be removed for the similarity with a child’s nude picture. The moderators can determine whether a photo should be neglected according to cultural values, whereas algorithms can’t. As for the question of democracy, these algorithms have always been developed relying on the company’s legally prescribed parameters. It means that the functions of legislation, judiciary and enforcement remain to be controlled by the company. As long as the Facebook’s management still consider the photo “child pornography,” the algorithm will continue to remove it, even more efficiently and decisively than manual reviewing.

In addition, algorithmic moderation reverses long-standing efforts by journalists and researchers on content moderation transparency. It’s hard for us to tell whether a human moderator or an algorithm deleted our post. And the exact criteria for making these takedown decisions are still unknown. The exact functions of these systems are deliberately obfuscated, and the database of prohibited content remains closed to everyone—including trusted third-party auditors and vetted researchers (Gorwa, Binns & Katzenbach, 2020). Algorithmic moderation appears to have helped companies find another way to circumvent regulation and pass the buck.

Conclusion

In summary, the content moderation mechanisms of current online platforms are formulated by private companies, which only reflect the values of a few people, resulting in many unreasonable moderation decisions and online social problems. Many scholars have questioned its democratic legitimacy and transparency.

The algorithmic moderation introduced subsequently exacerbated the impact of these issues. So, who should set the standards for the content moderation mechanisms of online platforms? The answer is still unknown so far, but I want to show an example here.

To combat terrorist speech on social platforms, the EU cooperated with large social media platforms such as Facebook and established the EU Internet Referral Unit (EU IRU) in 2015 to replace the subcontracted third-party content review companies. It reports contents to companies that violate the platform’s “Community Guidelines” and structurally intervene in its own content moderation workflow by identifying and flagging terrorist content. The EU European Parliament has also passed EU regulation against ‘terrorist’ content online (TERREG) in 2021, which requires platforms to take responsibility for protecting users from terrorism through legislation (Bellanova & Goede, 2021). These two initiatives successfully combined the two main bodies of platform regulation: the government and private companies, and effectively suppressed the spread of terrorism on social media platforms. The State-firm co-governance seems to be an excellent solution to the lack of transparency and accountability in the platform content moderation mechanism. Third parties or private institutions should also be involved. More joint governance approaches should be explored in the future.

References:

Angwin, J., & Grassegger, H. (2017). Facebook’s Secret Censorship Rules Protect White Men From Hate Speech But Not Black Children. Retrieved 7 April 2022, from https://www.propublica.org/article/facebook-hate-speech-censorship-internal-documents-algorithms

Bellanova, R., & Goede, M. (2021). Co‐Producing Security: Platform Content Moderation and European Security Integration. JCMS: Journal Of Common Market Studies. doi: 10.1111/jcms.13306

Facebook Community Standards. (n.d.). Retrieved April 7, 2022, from https://transparency.fb.com/en-gb/policies/community-standards/

Galantino, S.(2021). Speech Police: The Global Struggle to Govern the Internet. Florida Bar Journal, 95(3), 53+. Doi: https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A661471298/AONE?u=usyd&sid=bookmark-AONE&xid=ee0fc5ec

Gillespie, T. (2018). Custodians of the Internet: Platforms, Content Moderation, and the Hidden Decisions that Shape Social Media. New Haven: CT: Yale University Press.

Gillespie, T., Aufderheide, P., Carmi, E., Gerrard, Y., Gorwa, R., & Matamoros-Fernández, A. et al. (2020). Expanding the debate about content moderation: Scholarly research agendas for the coming policy debates. Internet Policy Review, 9(4). Doi: 10.14763/2020.4.1512

Gorwa, R., Binns, R., & Katzenbach, C. (2020). Algorithmic content moderation: Technical and political challenges in the automation of platform governance. Big Data &Amp; Society, 7(1), 205395171989794. doi: 10.1177/2053951719897945

Matamoros-Fernández, A. (2017). Platformed racism: the mediation and circulation of an Australian race-based controversy on Twitter, Facebook and YouTube. Information, Communication &Amp; Society, 20(6), 930-946. doi: 10.1080/1369118x.2017.1293130

Roberts, S. (2018). Digital detritus: ‘Error’ and the logic of opacity in social media content moderation. First Monday, 23(3). doi: 10.5210/fm.v23i3.8283

Roberts, S. (2019). Behind the Screen: Content Moderation in the Shadows of Social Media. (pp. 33-72). New Haven: CT: Yale University Press.

Suzor, N. P., West, S. M., Quodling, A., & York, J. (2019). What Do We Mean When We Talk About Transparency? Toward Meaningful Transparency in Commercial Content Moderation. International journal of communication [Online], 1526+. doi: https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A592665058/AONE?u=usyd&sid=bookmark-AONE&xid=cba8d7e3