Background

The formation of an intelligent society centered on the Internet has gradually brought the world into the era of digital human rights. Big data, blockchain, artificial intelligence, advanced algorithms and other scientific technologies have built new forms of social productivity tools, and productivity has developed rapidly, which in turn has led to the emergence of many new types of rights and obligations in human society, thus shaping a more complex entanglement of rights and obligations. According to Susi (2021), “Digital human rights” is one of the products of rights in the age of intelligence.

People are no longer just individuals in nature and society; in the virtual space constructed by the Internet, a large amount of data and information can represent the existence of people to a large extent. The “digital person” also enjoys certain rights, responsibilities and obligations due to his or her existence and social connection. The accumulation and analysis of information is an important basis for the birth of digital human rights, so the protection of digital human rights also includes the protection of personal information, and the most important piece of it is the protection of personal privacy.

In the new digital era of the smart age, the right to privacy presents new features such as the expansion of the scope of the object, the enhancement of economic value and the prominence of virtuality, which brings challenges to the protection of privacy.

The Facebook Data Leaks

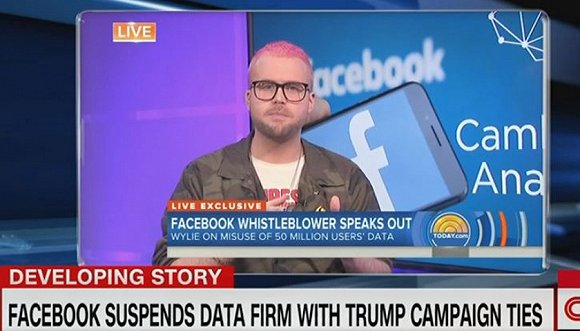

According to whistleblower Christoph Wiley’s allegations, Cambridge Analytica acquired the data of 50 million Facebook users before the 2016 U.S. presidential election. All this data was initially gathered by Alexander Kogan through a psychometric app called “This is Your Digital Life.” Using this app, Cambridge Analytica collected information regarding not merely the users taking Kogan’s personality test, as well as their friends, involving data on tens of millions of users (https://www.snopes.com/author/bethania 2018; Riley, 2018).

Because of the large amount of user information Facebook holds globally, with close to 30% of the world’s population registered for the social media account, the incident has attracted significant attention worldwide (Wattles, 2018). Observer’s “Revealed: Cambridge Analytica’s access to Facebook user information” report is publicly available and shows that key figures in the incident are the former president of Cambridge Analytica, SCL Inc. and Kogan of Cambridge Analytica London, among others. The companies involved are Cambridge Analytica, Global Scientific Research, the University of Cambridge and the University of St. Petersburg.

In 2009, there was an article in the Wall Street Journal titled “Putting Your Best Foot Forward”. The article analyzed how Facebook was able to stand out in the fierce social media wars of the time because users were “willing to trade their privacy for a platform of trust-based communication. In contrast to many anonymous platforms, Facebook gained the trust of its users by requiring them to register with their real identity information. However, does “real identity registration” imply a bottomless “privacy overdraft”? In this regard, it is necessary to define what privacy is and what personal information is.

The Impact of Changes in the Digital Age on the Right to Privacy

What kind of personal information is private? We should define privacy and citizens’ right to privacy not only from the nature of personal information itself, but also from the way and purpose of collecting and using information in the context of the development of the times.

For the first time, in 1890, American private law scholars Brandeis and Warren published “On the Right to Privacy” in the Harvard Law Review, introducing the notion of privacy “as “the right to be free from interference by others” (Warren et al., 2015) , arguing that only by defining this right is defined as “the broadest and most cherished of human rights” in order to guarantee the individual’s “beliefs, thoughts, emotions, and feelings”. Since then, the right to privacy, as an important part of citizens’ personality rights, has gradually been recognized and protected by the laws of various countries.

The right to privacy in the traditional sense cannot be directly equated with the right to privacy in the “digital human rights”. The positioning of the right to privacy in the digital era is very difficult. Although the law provides for the right to privacy, due to the rapid development of the Internet information society, the literal interpretation or even the expanded interpretation of many legislative provisions can no longer meet the needs of protecting citizens’ information claims. With the rapid development of the information society, the types of citizens’ personal information have long expanded to include personal reading preferences, shopping habits, chat logs of chat software, microblogs, etc. (Warren et al., 2015).

The smooth, rapid, and orderly development of an intelligent society requires mutuality of information, i.e., people understand each other’s behavior and respond to it; it also requires analysis and prediction of information, i.e., people predict each other’s expectations and make corresponding decisions and actions in response to each other, which is the embodiment of social activity.

However, with the development of the emerging platform economy, the consequences of such social activities are often too advanced, and the process of such analysis and prediction between Internet commerce platforms and users is often prone to the phenomenon of businesses using user information beyond the borders in order to gain economic benefits, such as the big data killing incident of China’s DDT taxi company, which generally pushed up prices for customers with better economic status and higher level of service choices.

Digital privacy as a kind of data has become part of the means of production in an intelligent society. Today, page views, targeted tweets, and the precise targeting of user markets are pathways to social wealth (Leonard, 2013), so much so that they can be considered readily realizable property.

The right to privacy in the digital age has a prominent and strong property nature and economic value that is unprecedented in traditional privacy rights (Rees, 2013). Data is the means of production in the new intelligent society, and to hold it is to hold the code to wealth (Leonard, 2013). However, it is not uncommon for the privacy rights of digital people to be violated by platforms, and the lack of government and social regulation of platform transgressions often leaves the rights of victims uncompensated, despite the fact that they are sometimes condemned by public opinion.

Compared to traditional privacy rights, privacy rights in the digital age are more vulnerable to infringement, and the consequences of infringement are often more severe in terms of performance and social impact.

Facebook’s Initiatives after the Data Leaks

1. An Escalation of the Facebook Deletion Campaign

In the wake of the user information leak, a global movement to resist Facebook has been started, despite the fact that those involved have tried to absolve themselves of blame for the incident, which had a massive effect on Facebook’s trustworthiness.

Searches on the Twitter site show influential campaigns have been going on since 2012. Using the keyword “delete Facebook” uncovered a total of more than 80,000 tweets with 1.37 million followers since its launch in 2012 (Nelson, 2018).

2. Adjustments to the Service for User Information

Facebook narrowed down its user information service business after the incident, with two measures on the level of program development and two on the level of actual users.

The first was to censor programs and platforms using user data and to notify subscribers of the potential impact (Leonard, 2013).

The second is to limit developers’ use of user data (Leonard, 2013). The software can access users’ full names, photos and email addresses without asking for permission, but if it needs access to more information, it needs to request it in advance.

Facebook has also issued two measures for specific users (Leonard, 2013). First, the company states that it will notify subscribers of programs that try to acquire their information to give them the choice of permitting access to personal information. In addition, the existing bug bounty feature, which rewards researchers for their positive role in keeping the site secure, will be improved.

Given that in the age of social media, the average user is less likely to discover network access to information, these operations are often more covert (Muradzada, 2020). In the event of an information breach, all result in a large amount of user information being leaked, yet the function is likely to lag badly in some cases due to its poor timeliness and inefficiency (Leonard, 2013).

In fact, there have been a number of incidents where users’ personal account information has been leaked on large public platforms. In 2016, Uber’s data of 57 million drivers and passengers was leaked; in the same year, Yahoo exposed the theft of 3 billion users’ login data in 2017, Equifax, a U.S. credit agency, leaked user information involving the privacy of up to 143 million U.S. users (Coyle, 2004).

The security of online information is a paradox that has existed since the birth of the Internet, but the problem is even more serious in the age of social media, mainly because user information is more complete and comprehensive than ever before, and the connection between user information and individual and group behavior of users has become stronger.

Analysis of Countermeasures for the Protection of Privacy in the Digital Age

1. National Legislation and Regulation

Due to the specificity of the smart social platform and the gap between the identity and ability of users, preventing the infringement of the privacy rights of digital people cannot be accomplished by market self-regulation alone, and requires the use of institutions and the rule of law to be adjusted by the government (Kulesza, 2013).

With regard to the construction of a legal regime for the protection of privacy in the digital age, we need a flexible and somewhat advanced legal system to adapt to the rapid changes in the relationship between rights and obligations in an inter-intelligent society.

For example, the General Data Protection Regulation of the European Union (Wankhede, 2016; Goodman, 2016) stipulates that the authorized use of information requires the consent of the subject of the information, and that this consent must be given in a specific and clear form with the full knowledge of the owner. For the development of the platform economy whether the access to user information is legal, legitimate and necessary will be a prerequisite for determining whether the act violates the right to information and personal privacy of digital people (Yordanov, 2017).

In addition, in the development of procedural law, in order to promote the realization of procedural and substantive justice and balance the relationship between the rights and responsibilities of platforms and users, the principle of reversal of the burden of proof can be adopted in cases related to the right to privacy in the digital age (Maras, 2015). Unless there are reasonable grounds, the platform should be able and obliged to provide data and collect and submit evidence, otherwise it should bear the legal consequences of losing the case.

2. Platform Regulation

In the context of national government regulation, there is a risk that macro regulations do not reach, or too strict regulations will not be conducive to the growth of intelligent society, artificial intelligence and other emerging digital industries in the economy, culture and other fields have its obvious superiority, we can not choke on it, so the platform itself to develop self-regulatory regulations is necessary (Keeling & Losavio, 2017; Knijnenburg, 2017).

Relatively fine-grained rules for information use and user instructions can help directly create a safe and efficient online environment for users to deal with their rights and responsibilities in a well-informed manner (Alan, 2015).

3. Social Monitoring Mechanisms

The social public who use Internet platforms and advanced algorithms, artificial intelligence and other services are the most direct participants and potential victims of privacy violations, and the monitoring of this group will directly and timely reflect social problems and social needs.

Platforms should comply with the contemporary social order for the ethical and moral codes and mandatory legal regulations within Internet companies and virtual spaces (Maras, 2015), nip inappropriate collection of user information in the bud through extensive social oversight, or provide effective post-event remedies to prevent the regeneration of violations.

Refenrence:

Alan Furman Westin. 2015. Privacy and Freedom. New York Ig Publishing.

Boehme-Neßler, Volker. 2016. “Privacy: A Matter of Democracy. Why Democracy Needs Privacy and Data Protection.” International Data Privacy Law 6 (3): 222–29. https://doi.org/10.1093/idpl/ipw007.

“CNN Video Experience | CNN.” 2022. Cnn.com. 2022. https://edition.cnn.com/videos.

Coyle, Karen. 2004. “The ‘Rights’ in Digital Rights Management.” D-Lib Magazine 10 (9). https://doi.org/10.1045/september2004-coyle.

Goodman, B. 2016. “Discrimination, Data Sanitisation and Auditing in the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation.” European Data Protection Law Review 2 (4): 493–506. https://doi.org/10.21552/edpl/2016/4/8.

https://www.snopes.com/author/bethania. 2018. “Cambridge Analytica Parent Company Banned by Facebook Has Contract with State Department.” Snopes.com. March 20, 2018. https://www.snopes.com/news/2018/03/20/cambridge-analytica-parent-company-banned-facebook-contract-state-department/.

Isidore, Chris. 2018. “Facebook’s Value Plunges $37 Billion on Data Controversy.” CNNMoney. March 19, 2018. https://money.cnn.com/2018/03/19/news/companies/zuckerberg-net-worth/index.html?iid=EL.

Keeling, Deborah, and Michael Losavio. 2017. “Public Security & Digital Forensics in the United States: The Continued Need for Expanded Digital Systems for Security.” The Journal of Digital Forensics, Security and Law. https://doi.org/10.15394/jdfsl.2017.1452.

Knijnenburg, Bart P. 2017. “Privacy? I Can’t Even! Making a Case for User-Tailored Privacy.” IEEE Security & Privacy 15 (4): 62–67. https://doi.org/10.1109/msp.2017.3151331.

Kulesza, J. 2013. “International Law Challenges to Location Privacy Protection.” International Data Privacy Law 3 (3): 158–69. https://doi.org/10.1093/idpl/ipt015.

Leonard, P. 2013. “Customer Data Analytics: Privacy Settings for ‘Big Data’ Business.” International Data Privacy Law 4 (1): 53–68. https://doi.org/10.1093/idpl/ipt032.

Luhmann, Niklas, and Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden. 2018. Die Soziologie Und Der Mensch. Wiesbaden Springer Vs.

Maras, M.-H. 2015. “Internet of Things: Security and Privacy Implications.” International Data Privacy Law 5 (2): 99–104. https://doi.org/10.1093/idpl/ipv004.

Muradzada, Nijat. 2020. “An Ethical Analysis of the 2016 Data Scandal: Cambridge Analytica and Facebook.” Scientific Bulletin 3: 13–23. https://doi.org/10.54414/yzuf7796.

Nelson, Daniel. 2018. “Mozilla Creates Facebook Extension to Give Users Facebook Data Privacy and Prevent the Collection of Information.” Science Trends, April. https://doi.org/10.31988/scitrends.14932.

Rees, C. 2013. “Tomorrow’s Privacy: Personal Information as Property.” International Data Privacy Law 3 (4): 220–21. https://doi.org/10.1093/idpl/ipt022.

Riley, Charles. 2018a. “Facebook Bans Far-Right Group Britain First.” CNNMoney. March 14, 2018. https://money.cnn.com/2018/03/14/technology/britain-first-facebook-ban/index.html?iid=EL.

———. 2018b. “What You Need to Know about Facebook’s Data Debacle.” CNNMoney. March 19, 2018. https://money.cnn.com/2018/03/19/technology/facebook-data-scandal-explainer/index.html.

Susi, Mart. 2021. “Reflections on Digital Human Rights Practice Research and Human Rights Universality.” East European Yearbook on Human Rights 4 (1): 52–58. https://doi.org/10.5553/eeyhr/258977642021004001004.

Wankhede, A. 2016. “Data Protection in India and the EU”: European Data Protection Law Review 2 (1): 70–79. https://doi.org/10.21552/edpl/2016/1/8.

Warren, Samuel D, Louis Dembitz Brandeis, and Steven Alan Childress. 2015. The Right to Privacy. New Orleans, La.: Quid Pro Books.

Wattles, Jackie. 2018. “Mark Zuckerberg and Facebook under Fire from Politicians over Data Controversy.” CNNMoney. March 18, 2018. https://money.cnn.com/2018/03/18/technology/business/mark-zuckerberg-facebook-politicians-data/index.html?iid=EL.

Yordanov, A. 2017. “Nature and Ideal Steps of the Data Protection Impact Assessment under the General Data Protection Regulation.” European Data Protection Law Review 3 (4): 486–95. https://doi.org/10.21552/edpl/2017/4/10.