In this blog, I will attempt to critically analyse and deconstruct the controversial privacy threats that global citizens face in the digital environment and cyberspace, in the social and cultural context of the current digital age. To demonstrate that in the current Internet environment of the digital age, the information hegemony of privacy constituted by digital technology, the data industry, and the business logic behind it imposes imperceptible censorship and filtering on vulnerable individual digital participants. This further formed an Internet privacy governance dilemma.

Additionally, these potential technology ethics issues will be further identified and dismantled in the related blog case study thread, to gain valuable cultural analysis and discourse on digital privacy governance. Especially when digital citizens have to respond passively to these privacy rights that veiled disintegrate and dissipate in the digital society, space, and culture. When exposed to risks digital hybrid environment is generated by algorithms, artificial intelligence, and big data platforms.

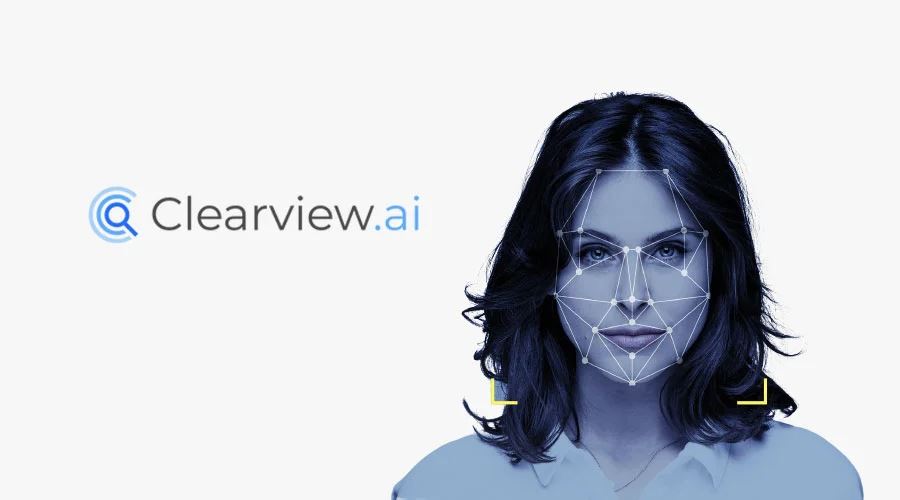

In the blog case study, I will focus on the principal analysis and sampling with a facial recognition technology and data company from the US – Clearview AI. Its business model is based on recognising the public’s facial biometrics, reflecting a unique phenomenon of privacy vulnerability and individual vulnerable responses in the digital age. Clearview AI through self-developed digital tools application, including algorithms, artificial intelligence, and big data, to achieve the integration and output of the corresponding personal identification information obtained through the facial images’ information input (Burgess, 2022). This process obtains user facial images and identity information from Internet infrastructure with extensive users. Furthermore, sell access and license to this information retrieval capability as its profitable business model. Even though, Clearview AI (2021) claims this will be limited to specific law

The image of the Clearview AI (Clearview AI, n.d.)

enforcement and limited public agencies. However, this controversial business model reflects acute threats in the current digital landscape of the Internet, which datafication of personal privacy and the privacy risks individuals and digital citizens face.

Bidirectional Deconstruction and Industry Motivation of Digital Privacy

In the digital age, individuals’ spatial division and perceived motivation for the identification of privacy rights have been beyond the actual physical space in traditional cultural concepts and legal definitions. Also, this threat of privacy disclosure and commercialization of privacy has been widely derived to cyberspace with potential uncontrollability and more significant profit motives – the Internet. Marwick and Boyd (2018) points, individual private information and biological data here have been regarded as digital product and resource with practical value and transformation ability. Therefore, around privacy rights – a social concept of universal value, the relevant industrial and economic frameworks were generated, and they can be combined with a more comprehensive economic industry and capital platform. Typical examples include targeted marketing, digital advertising, and big data speculation. However, some of the more invasive and oppressive commercialization of public privacy is more worrying and uncomfortable; for instance, the identification of individuals based on facial data, primarily when these behaviours are based on lucrative business motives. Further, when the collected digital privacy becomes a kind of identity identifier and clue, relevant stakeholders can reversely identify, describe, and sample the individual identity information (Mirzoeff & Gonzaga, 2021).

Therefore, in this digital environment where there is a direct value demand for individual information and data, the social and cultural behaviours that individuals realize and carry out on the Internet will also encompass rights appeal from traditional privacy claims. However, these privacy – personal information and data leftover from Internet activity, after specific integration, analysis, and reshaping, can become digital clues for identification and description of the individual. Suzor (2019) argued, human biology privacy has also become an integral part of Internet privacy in this particular value context. Among them, facial biometrics is a straightforward targeted privacy case. Personal facial information is an easily accessible privacy resource for entities interested in privacy, like user-profiles and common selfies on social networking sites. It has a unique direction for individual identification; most people obviously have different looks. Therefore, existing digital biometrics and facial recognition will be able to identify and correlate this identity information on the Internet accurately. The intervention of artificial intelligence analysis and automated big data mining makes this privacy collection and analysis behaviour efficient and secret, even without user knowledge and identification (Candelon, di Carlo, & Mills, 2021). Therefore, this kind of personal information and privacy which can be directly transformed with commercial value, makes it a near-free source of data assets for interested entities. The enormous amount of Internet information has become a natural source of privacy violations and collections, along with personal information, like selfies, emails, phone numbers, and even addresses those individual users voluntarily upload.

Under this trend, when users’ digital privacy has become a direct source of business value, different stakeholders regard this as a direction to clear benefits. Capital, platform, and possessed technical capabilities seem to point to snooping on user privacy (Tumber & Waisbord, 2017). Thus, for the user at the core of this circle, this creates a paradox, enjoy free services, resources, and content from the Internet; however, their private information has also become a free resource that can be obtained on the Internet. This peculiar phenomenon of privacy information and data circulation demonstrates the privacy issues that cyber citizens must face in the digital age – how to apply the right to informed consent accurately in their digital behaviour, and their boundaries of self-defence. However, user-generated digital privacy is an information resource that will be a considerable benefit for interested entities. User privacy as this valuable digital core, its clear appeal will be reflected in their continued demand for user information, and technological reprocessing. Therefore, on the results of the digital age, based on the participation, realization, and construction of digital citizens in cyberspace, these social behaviours derived from active, or passive make the so-called absolute privacy claim a nihilistic idealized concept.

Case Study: Clearview AI – an Incompatible Privacy Interactions

The case study section will critically examine Clearview AI from a digital perspective and ethical framework; it is a facial recognition technology company, and an individual identification provider has an apparent privacy dispute. Moreover, further, interact and verify the topic of this blog to reflect the potential threats and violations of individual privacy rights when facing digital technology products and interest motives in the context of the digital age. Clearview AI is a company that uses digital technology to analyse and recognize facial photos on the Internet. Through specific algorithm work and artificial intelligence participation, it has acquired the ability to identify and locate the identity of the face owner through images (Burgess, 2022); in the case of image source, it obtains the ability to access and disclose individual private identities through data mining and big data integration of massive Internet image information.

Clearview AI has mastered a substantial facial information database in terms of business model through those mentioned above digital technical means. Based on this, it provides an identity information search engine with identification services to customers. According to The Washington Post (Harwell, 2022), Clearview AI have identified and stored more than 10 billion facial images and built a web of information and relationships related to them.

The image of the public identification (Clearview AI, n.d.)

The sources of these visual information content generally come from the public information of Internet infrastructure users, for instance, social media platforms, video platforms, and public media. What is more worrying is that this digital privacy content request, analysis, and expansion formed by Clearview AI does not require the face owner’s informed consent and ethical permission. Smith and Miller (2021) argued this make this digital technology capability built on the face owner’s rubble right to privacy. This unequal right discourse system negatively affects individual users in the digital age. The technological wave and application development in the digital age finally split the balance in the traditional individual rights system. This is mainly reflected in the confrontation of the right to privacy. Internet users have become a specific rights vulnerable party. Clearview AI formed a technological situation and technological determinism through the advantages of digital technology out of the balance of privacy rights.

However, in this dispute over private ownership of facial biometric data, Clearview AI maintains an inflexible posture; it attempts to argue and strip away the individual’s definition of self-face ownership. Its claims (Harwell, 2022) that human facial information is a public resource that is not recognized by law. This vague claim reflects a conflict over privacy. This claim also confounds the connection between privacy and public resources, in an attempt to justify Clearview AI’s controversial privacy business. From this perspective, the advent of the digital age has led to the creation of privacy nihilism; individuals in Internet applications begin to lose the right to control and decide on their privacy (Flew, 2019), these digitized personal rights are being transferred in a subtle form to third parties and interested entities; which individuals are difficult to confrontation, or even reaction. Therefore, the technological supremacy, technology priority, and demand-driven represented by the digital age have made the public at a technological disadvantage to lose absolute control and influence over privacy.

GDPR: a New Paradigm of Digital Privacy

Based on the characteristics and methodology of information business in the digital age, many technology and internet companies incorporate user privacy as part of their business model, further building new digital business-driven strategies. However, the over-expansion of technological capabilities in the digital context has gradually eroded the adequate response space and coping function of individual privacy rights.

In this digital age full of user information and sensitive privacy, both data and technology companies are keen to use ethical marketing and user agreements to guarantee immediate access to user privacy (Denley, Foulsham & Hitchen, 2019). Moreover, use the privacy statement, which attempts to be ethically compliant and legalized, to make a persistent statement that some degree of digital privacy is necessary to acquire and use, and render it a reciprocal digital act. For instance, to enhance browsing experience or more precise content recommendation. However, this may also be limited to a subtle hint of a dualism of rights – that is, the right to access and use these digital services, content, and experiences comes at a price of certain privacy rights. In a broader perspective, privacy becomes a valuable object, a currency, a digital resource that can be traded, enabling users to navigate cyberspaces and access frameworks (Marwick & Boyd, 2018). However, in the case of Clearview AI, it shows that, its application mechanism and business model completely override the users whose privacy is collected. This unilateral privacy collection and benefit generation makes user privacy a catalyst for commercial interests. Instead, a privacy collection mechanism similar to platform capitalism is generated. Even Clearview AI was claimed it is used to combat crime and potential threats in cooperation with law enforcement agencies. However, it is questionable whether the procedural justice in this cooperation process and privacy protection involving a wide range of public interests have been appropriately treated and applied.

Therefore, when business models and information services in the digital age are unavoidable for the use and acquisition of personal information or privacy, industry application norms, information application transparency, and legislative principles provide a promising paradigm for the application of information and privacy. For instance, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which came into effect in 2018 in the European Union, defines citizens’ ownership of personal data and digital privacy legally and regards it as a personal digital asset with legal benefits and value (Harris, Samuel & Probert, 2018). The personal privacy information and digital biometric data previously collected and analysed by privacy gainers like Clearview AI are protected. Therefore, the application of GDPR provides a powerful paradigm and reference for applying technology ethics. Potential privacy threats and moral risks are dismantled in advance through legislation and ethical restraints, then passed an ethical standardization privacy use mechanism, as a user protection mechanism. GDPR provides a good governance paradigm for user privacy anxiety in the current digital age, with an identification mechanism. A balance between users and technical entities is formed through the division of power subjects and obligations.

Conclusion

Digital privacy has been integrated into the thread of digital citizens as a unique technological concept that accompanies the digital age’s rise. This neutral technology concept provides both digital convenience and economic value to stakeholders and potential beneficiaries. However, Clearview AI’s case study shows that this seemingly harmonious and fair privacy dualism also has ethical and technical dilemmas, like information misuse and threats. This has further led to public concerns about threats to digital privacy. This is especially true when technological superiority can deprive the individual of the right to response space. Thus, a case like GDPR proves this normative paradigm could eliminate this technical bias to rebalance privacy rights.

References

Burgess, C. (2022). Clearview AI commercialization of facial recognition raises concerns, risks. CSO (Online).

Candelon, F., di Carlo, R. C., & Mills, S. D. (2021). AI-at-Scale Hinges on Gaininga ‘Social License’. MIT Sloan Management Review, 63(1), 1-4.

Clearview AI, Inc. (2021). Law Enforcement. https://www.clearview.ai/law-enforcement

Denley, A., Foulsham, M., & Hitchen, B. (2019). GDPR: how to achieve and maintain compliance. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429449970

Flew, T. (2019). Platforms on Trial. Intermedia, 46(2), 18-23. https://eprints.qut.edu.au/120461/

Harris, D., Samuel, S., & Probert, E. (2018). GDPR confusion. The Veterinary Record, 183(12), 388–388. https://doi.org/10.1136/vr.k3956

Harwell, D. (2022, February 16). Facial recognition firm Clearview AI tells investors it’s seeking massive expansion beyond law enforcement. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2022/02/16/clearview-expansion-facial-recognition/

Marwick, A. E., & Boyd, D. (2018). Understanding Privacy at the Margins: Introduction. International journal of communication, 12(1), 1157-1165.

Mirzoeff, N., & Gonzaga, S. (2021). Artificial vision, white space and racial surveillance capitalism. AI & Society, 36(4), 1295-1305. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-020-01095-8

Smith, M., & Miller, S. (2021). The ethical application of biometric facial recognitiontechnology. AI & Society, 37(1), 167-175. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-021-01199-9

Suzor, N. P. (2019). Who Makes the Rules?. In I. Editor (Ed.), Lawless: The Secret Rules That Govern our Digital Lives (pp. 10-24). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108666428

Tumber, H., & Waisbord, S. (2017). The Routledge Companion to Media and Human Rights (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315619835