Introduction

In the post-modern society, algorithm recommendation technology is bringing people into the era of information dissemination with personalisation, customisation and intelligence. The phenomenon of filter bubbles generated by algorithm has also triggered a series of important concerns and considerations for the impacts of internet and platforms governance on social development and political democracy in the western society. The purpose of this essay is to analysis and discuss how does filter bubble and opinion polarisation closely related to western political democracy and provide considerations and insights on algorithmic governance.

Understanding Filter Bubble

The term of “filter bubble” was coined by Eli Pariser in his book The Filter Bubble: What the Internet Is Hiding from You. Pariser (2011) pointed out that filter bubble refers to the algorithm filtered out information that contradicts audience’s opinions or the content they do not interested in based on individuals’ past searching history, and only provides what they want to see, thereby creating a state of cognitive isolation and social fragmentation. In the other words, the concept of “filter bubbles” indicates that user-oriented personalized recommendation algorithms limit the scope and channels of users’ exposure to new information, making users gradually confined to homogeneous information bubbles.

Opinion polarization

Similar to echo chamber, the metaphor of “filter bubble” also raise the concern of group polarization. It also isolates users from other information, who are immersed in a world of information that meets their preferences, and it is difficult for users to actively break through barriers to find new information, which intensifies the polarization of opinions. Opinion polarization has gradually become an important research topic in media study and its discussion mainly revolves around increasing social and political polarization in democracies. Opinion polarization is related to the selective psychological mechanism of the audience. The term “confirmation bias” describe the tendency of people to accept information that is more consistent with their original attitudes and try to avoid those that are inconsistent with their own opinions (Kolbert, 2017). In the new media environment, the algorithm has solidified the confirmation bias. The personalized information recommendation algorithm conducts personality analysis based on the individual’s previous reading preferences and browsing history and repeatedly recommends homogeneous information that conforms to the user’s political inclination.

Gatekeeper of Journalism: Citizenship vs Consumers

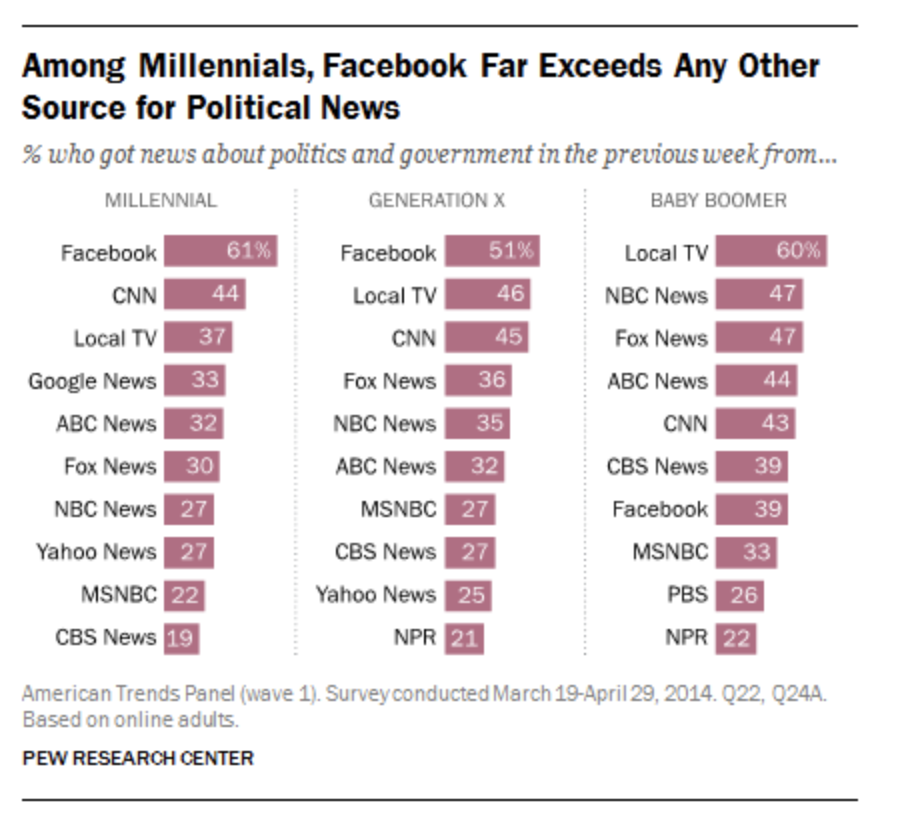

The worries that filter bubbles and opinion polarization may destroying democracy is necessary. The dominance of the platform algorithm makes it a new way of constructing real-world knowledge (Just and Latzer, 2019). One of important consideration is that platform capitalism is gradually replacing traditional mass news media as the new gatekeepers of journalistic industry, which also affecting and challenging the role of citizens, the formation, structure and operation of political democracy in the western country. Mitchell et al (2010) argues that Facebook is becoming the primary source of political news for millennials in the United States. According to Pew Research Center, the data (figure 1) shows that 61% of the Millennium and 51% Generation X has highest degree of dependence on Facebook to access political news. Baby boomer showed a different tendency, with 60% of respondents choosing local TV as their main source for getting political news.

Figure 1:Political news ranking of different age groups in the U.S.

Source:(Mitchell et al., 2010)

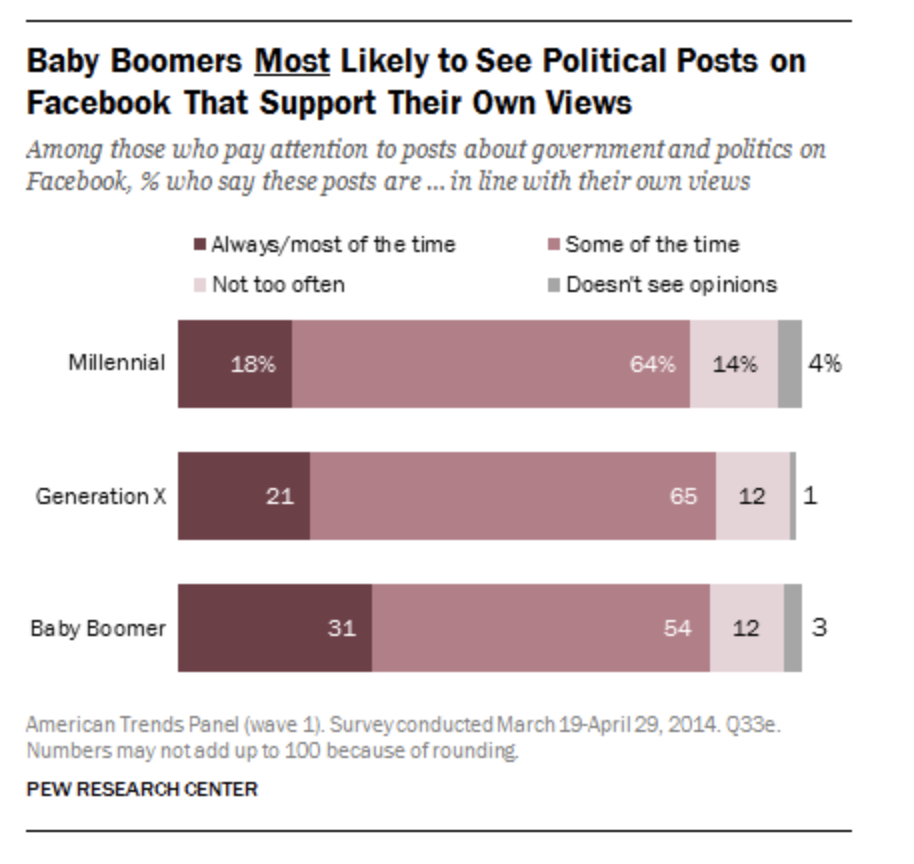

The survey results (figure 2) also illustrate that the majority of American users in all age groups indicate that most of Facebook’s political posts align with or support their own views. This numerical evidence shows that younger users are more likely to use Facebook for government and political news than older users (Mitchell et al., 2010). In addition, according to a Reuters Institute report, as many as 40 per cent of Australians used Facebook for news – making it the country’s most popular social media and messaging platform between 2018 and 2020 (Mao et al., 2021).

Figure 2: Percentage of Facebook political posts that match users’ political views in America.

Source: (Mitchell et al., 2010)

The news trending of both the US and Australia illustrates the penetration and popularity of social platforms continue to invade and reshape the changes in news sourcing and production relations. Mancini (2013) pointed out that media fragmentation is creating a crisis in traditional journalism and thus affecting democratic structures. On the one hand, the fundamental driving force behind the operation of platform capitalism is completely different from the developmental purpose of the traditional gatekeepers of mass media news organization, such as Public Broadcasting Services (PBS), as result platform algorithms has challenged the identification of citizenship of news publics.

Brevini (2013) developed a new normative framework of PBS and held accountability to the tendency of reducing the role of citizens to consumers in the media, who argues that “if we limit the dynamics of democracy to individual choices and preferences, then we totally lose the collective dimensions of citizenship” (Brevini, 2013). In the postmodern society, the idea of democracy should be built in a society in which multiple forms of hegemony are compatible with each other (Brevini, 2013), which the citizenship means that the individual’s unique civic and political consciousness should take place in a process that “never stops renegotiating the common interests” (Brevini, 2013). This entitlement and consensus require a diversity of news content available to the public and an important function of the news media is to facilitate the necessary negotiations and agreements, “where one can meet with others and get in touch with their needs, opinions, and proposals may be missing” (Mancini, 2013).

For example, the continuing functions and responsibilities described by the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) Charter (2021) under ABC Acts state that the broadcaster’s programming should “contribute to a sense of national identity and inform and entertain, and reflect the cultural diversity of, the Australian community”. Legal constraints and professionalism ensure that the journalistic practice and development of national mass media institutions is operated based on the correct democratic structure and agenda, the role of nation public is identified as citizen instead of consumers. As Andrejevic (2019) argues that “political sovereignty requires the practices of recognition that make it possible to form preferences in discussion with others, taking into consideration their perspectives and claims”.

Citizens can learn about different types of information through news published by professional news organizations, thereby developing democracy in the richness of diverse news content that is not personally biased or content limited. Unlike traditional mass media institutions, platform capitalism concerned with maximizing the commercial benefits through algorithmic technology, so it defines the public as consumers than political citizens in a greater extent. Consumer sovereignty and algorithms will indirectly facilitate users’ selective consumption of news content. Lewis (as cited in Brevini, 2013) pointed out that compared to citizens, the expression of consumers is limited by economic relations and markets. Platform capitalism and algorithmic recommendation have changed people’s interaction patterns and the diversity of content acquisition, making online news users’ identity as citizens or consumers becoming blurred, which is affecting the formation of democratic structures and objectivity. Citizens’ opinions will be strengthened rather than open to new ideas and feelings (Mancini, 2013).

Algorithm and Political Election

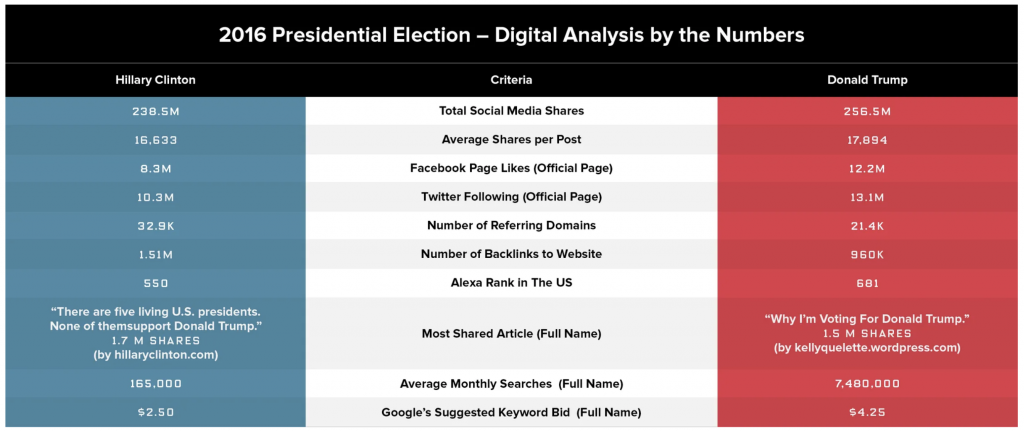

On the other hand, the context of social media filter bubbles and algorithms also affect democratic political elections. A media study conducted by (Guess et al., 2018) with the United States as a specific context provides useful and important evidence on how filter bubbles helped Donald Trump win the 2016 U.S. presidential campaign. The study shows that vast majority of fake news sites are produced and consumed in support of Trump, and Facebook, as the most popular battleground in the US election, has an obvious and important role in guiding people to visit fake news (Guess et al., 2018). In addition, the graph (figure 3) shows the statistics comparison in aspects of social media followers, site performance and Google search stats of Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump on the day before the US election. Metrics tell a fact is that Donald Trump has higher popularity on social media.

Figure 3: 2016 Presidential Election candidate online indicator comparisons.

Source: (Mostafa, 2017)

However, people are unaware of how algorithms have a powerful influential role in their political voting and participation. Pasquale (2015) proposed the “One-Way Mirror” metaphor, where platform capital manipulates and shapes the details of people’s daily lives, yet people are ignorant of the impact of these power decisions. The selective information exposed by fake news, driven by algorithms, will inevitably and implicitly shape people’s conscious tendencies towards party candidates and political positions. Philip argues that there is a lot of misinformation in the public domain, which Trump ‘s election and its results is one of cases of misinformation in the democratic movement (Hern, 2017). Emily described Facebook’s impact on democratic societies as “insidious” and that users of the algorithm programmed an elaborate information environment, “where we never see anything outside our own bubble … and we don’t realise how curated they are” (as cited in Hern, 2017).

Algorithm and Internet governance

Whether it’s a crisis in journalism, citizenship or the impact of fake news on democratic elections, which all revolve around the internet governance issues of algorism between the rise of digital platforms and the opinion polarization of society. Platform companies already have an unshakable economic status, along with their continuously expanding business scale worldwide and the increasing importance of database in economic operations. How to deal with the increasingly uncontrollable power of platform companies is a question that must be addressed. Platform capitalism uses technological advantages and big data to reshape the working mechanism of the reproduction of social relations.

There are many aspects to consider in its power structure and logical constraints and regulation. One of important concern is the algorithmic transparency. Algorithmic technology-driven digital platforms, such as Google, Facebook or Twitter, often operate in the way of “black box society” (Pasquale, 2015), which its inner working considered as unknown parameters that are inextricably linked to patent and trade secret laws, nondisclosure agreements, non-compete clauses, and other legal instruments (Hallinan and Striphas, 2016). The opacity of the algorithm is not only limited to its importance as the commercial core competitive value of platform capital that was protected by confidentiality clauses, the challenge of technical rules and logic of recommending algorithm are even more obscure to understand to the public. For example, the competition of Netflix Prize reveals the development process and details of the algorithmic recommendation system to the public. An interesting insight developed by Hallinan and Striphas (2016) is that the decision making of platform algorithm that suggest the recommended content to users, which are determined based on two dimensional; (1) explicit cultural identities of audience, such as demographic information of age, gender and education levels, and (2) the Implicit attributes, which refers as potentially imperceptible understanding and classification of users. Another important consideration is who make the rule. Suzor (2019) pointed out that the regulation and governance of content on platforms such as Facebook is critical to their viability, but relying on the platform itself is not enough. Each user and individual have different preferences and acceptance levels of content.

On the one hand, if the algorithm technology is not properly governed and regulated, the personalized content services it provides will continue to generate the phenomenon of opinion polarization. This will result in citizens lacking access to diverse content and diverse opinions to think beyond their narrow self-interest in democratic politics. On the other hand, the platform unable to cater every content feedbacks or post opinions in time, which requires substantial human resources and costs spending. More importantly, the existence of personalized service itself is to create user stickiness, which the essential intention of platform to develop algorithmic technology is always profit-oriented. Platforms need regulation and governance in response to respect public opinion for future longer-term operations.

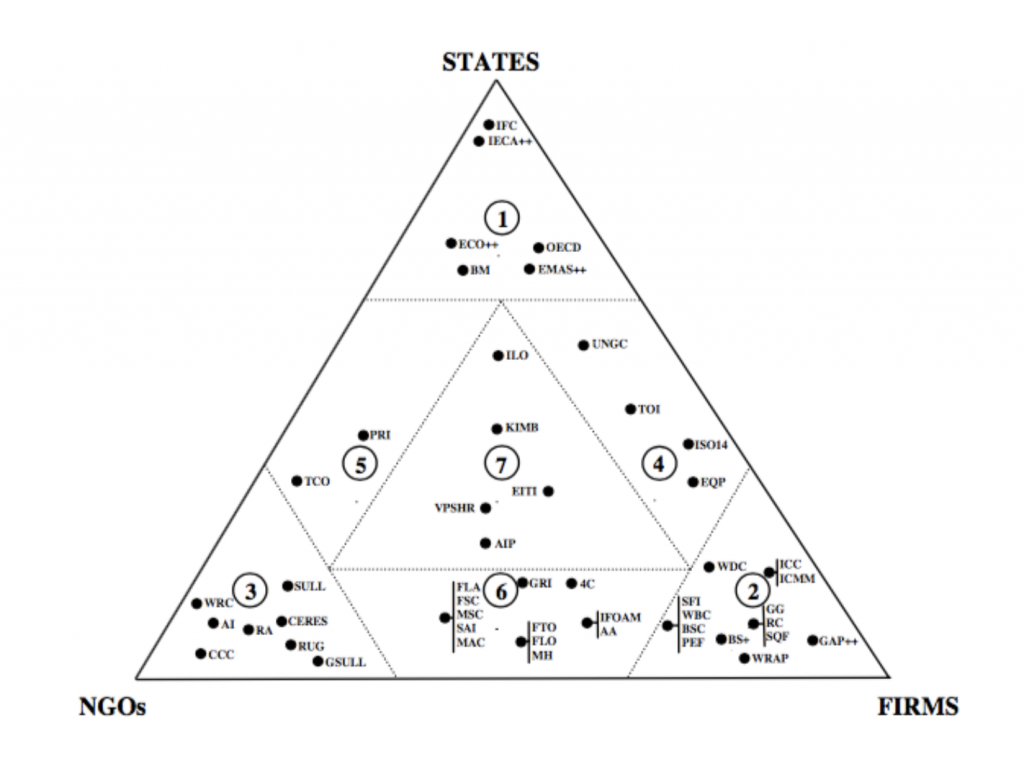

Figure 4: The Governance Triangle

Source:(Gorwa, 2019).

It suggests that the model of “the Governance Triangle” (Figure 4) can be applied to governance filter bubbles and opinion polarization, which provide a more comprehensive platform regulatory ecosystem. States, non-government organization (NGO) and firms (platforms) form a stable state of checks and balances between nations, citizens and interests. This constraint can ensure that the government can strengthen the stable and reliable supervision ability of the democratic political structure and decision-making process. At the same time, NGOs take the public standpoint to reduce and avoid the continuous exploitation of users by platform capitalism and worsen the opinion polarization.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the platform algorithm generates filter bubble which increased opinion polarization. Platform capitalism is replacing the traditional role of the gatekeeper of the traditional and professional news media institutions, thereby blurred the identity of citizenship of national public when they are experiencing civic engagement in political election and social formation. In addition, the algorithmic governance of the platform needs to consider two important factors: algorithm transparency and regulatory entities, and it is recommended to use the governance Triangle as a governance model to regulate opinion polarization.

Reference

Andrejevic, M. (2019), ‘Automated Culture’, in Automated Media. London: Routledge, pp. 44-72.

Brevini. (2013). A Normative Framework for PBS Online: The Idea of PSB 2.0. In Brevini, Public Service Broadcasting Online: A Comparative European Policy Study of PSB 2.0 (pp. 30–53). Palgrave Macmillan.

Gorwa, R. (2019). The platform governance triangle: Conceptualising the informal regulation of online content. Internet Policy Review, 8(2).

Guess, A., Nyhan, B., & Reifler, J. (2018). Selective Exposure to Misinformation: Evidence from the consumption of fake news during the 2016 U.S. presidential campaign. European Research Council, 1-49.

Hallinan, B., & Striphas, T. (2016).Recommended for you: The Netflix Prize and the production of algorithmic culture. New media & society, 18(1), 117-137.

Hern, A. (2017). How social media filter bubbles and algorithms influence the election. The Guardian. Retrieved April 6, 2022, from https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2017/may/22/social-media-election-facebook-filter-bubbles.

Just, N., & Latzer, M. (2019). ‘Governance by algorithms: reality construction by algorithmic selection on the Internet’, Media, Culture & Society 39(2), pp. 238-258.

Kolbert, E. (2017). Why Facts Don’t Change Our Minds. New Yorker. Retrieved April 6, 2022, from https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/02/27/why-facts-dont-change-our-minds.

Mancini, P. (2013). Media Fragmentation, Party System, and Democracy. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 18(1), 43–60.

Mao, F., Tan, Y., & Cheetham, J. (2021, February 18). Facebook Australia row: How Facebook became so powerful in news. BBC News. Retrieved April 6, 2022, from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-australia-56109580.

Mitchell, A., Gottfried, J., & Matsa, K. E. (2010). Facebook Top Source for Political News Among Millennials. Pew Research Center. Retrieved April 6, 2022, from https://www.pewresearch.org/journalism/2015/06/01/facebook-top-source-for-political-news-among-millennials/.

Mostafa, M. (2017). Your Filter Bubble is Destroying Democracy. Wired. Retrieved April 7, 2022, from https://www.wired.com/2016/11/filter-bubble-destroying-democracy/.

Pariser, E. (2011). The filter bubble: What the Internet is hiding from you. New York: Penguin Press.

Pasquale, F. (2015). ‘The Need to Know’, in The Black Box Society: the secret algorithms that control money and information. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, pp.1-18.

Suzor, N. P. (2019). ‘Who Makes the Rules?’. In Lawless: the secret rules that govern our lives. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 10-24.

The ABC Charter. (2021). Legislative framework. ABC News. Retrieved April 6, 2022, from https://about.abc.net.au/how-the-abc-is-run/what-guides-us/legislative-framework/.