Introduction

The Internet has entered Web 2.0, also known as the social media era. The Internet has provided users with unprecedented access to information. Social media platforms such as Facebook have allowed users to “become content creators in a more structured environment,” significantly lowering the barriers to content creation (Baehr & Lang, 2012). The mass media that emerged in the 20th century is also being replaced by automated media, which people are increasingly using as intermediation to access information, fragmented and personalized (Andrejevic., 2019). Such a large amount of information is challenging to manage, so both platforms and users filter information somehow or with tools.

Moreover, this process results in a higher degree of personalization. The user’s access to information and the platform’s information push becomes customized content based on the user’s past browsing data (Nikolov, 2015). According to Pariser (2011), a customized information environment leads to a narrowing of the user’s horizons and a narrower exposure to perspectives, leading to a filter bubble or an echo chamber. It is by no means alarming that this will hinder users’ access to different or opposing points of view and cause the consequence of ideological polarization.

A study conducted by the Pew Research Center in 2014 shows that political polarisation in the United States has increased dramatically in the 20 years of information technology development. There has been a significant increase in the number of people from both parties who negatively view the other party. People are more likely to delve into their own party’s political views than understand the other party (Pew Research Center., 2014). And filter bubbles have an essential role to play in this phenomenon. However, filter bubbles are not the only cause of ideology polarisation, and blaming everything on filter bubbles is certainly an overreaction and can lead to the ignorance of other internet governance issues.

This blog will look at the definition of a filter bubble, or echo chamber, and explain its impact on users. Following an analysis of the fake news phenomenon on Facebook concerning filter bubbles in the US 2016 election, following with summarising the scholarly debate on filter bubbles and other ideology polarisation causes. Then offer thoughts on countering filter bubbles and ideological polarisation regarding the users themselves, algorithmic technology, and society.

What is Filter Bubble

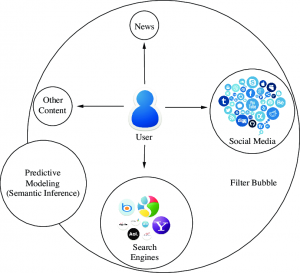

ResearchGate. Predictive Modeling Approach for Filter Bubble Bursting. [Download Image].

The filter bubble is a concept introduced by Pariser (2011), which means a space of information unique to the user. It is a state of intelligent isolation in which a website algorithmically separates users from information that holds different opinions to remain in their comfort zone for a long time. On the other hand, the echo chamber is a concept introduced before the filter bubble. It refers to a media in which the ideology of the individual is amplified or reinforced through communication and response in a closed environment (Sunstein, 2001). For the current academic community, as the two concepts have become increasingly overlapping and intertwined, they have become interchangeable and are widely used in various academic content (Bruns, 2019).

As previously stated, personalization is a fundamental cause of filter bubbles. The emergence of the definition of filter bubbles can be seen as reflecting widespread concern about the pre-determined personalization of platforms (Pariser, 2011). This concern is undoubtedly justified, as according to Nikolov’s research, the diversity of information available through social media is significantly lower than that available to users searching on their own (2015). Moreover, a report back in 2016 showed that 62% of young Americans use social media to get information, with 66% of Facebook users relying on the platform for news (Gottfried, 2016). It is conceivable that this trend will continue to go up in the last two years with predictable dangers.

Pariser argues that filter bubbles deconstruct or direct users’ online identities towards consumerism and individualism. They create the impression that the user’s self-interest and thoughts are all that matter (2011). This undoubtedly harms the online discussion environment and makes it more difficult for social media users to communicate. This guidance is difficult to detect and can impact user autonomy (Zuiderveen, 2016). And this user’s self-interest and thought can also extend to individuals or collectives who share the same opinion as to the user. Research has shown that homogenous communities or groups of people tend to become more extreme in their thinking (Pew Research Center, 2014).

Moreover, in a pluralistic society, on the one hand, people need adequate access to different perspectives to develop themselves in order to avoid getting caught in a spiral of reinforcement of their attitudes. On the other hand, people in society need the same information to create a shared experience and keep the social climate stable (Sunstein, 2001). This is not easy to do for users who are caught in a filter bubble. Which leads to a constant reinforcement of attitudes by users as a community or group of people, thus becoming ideology polarisation.

Case Study:2016 Facebook Fakenews during US Election

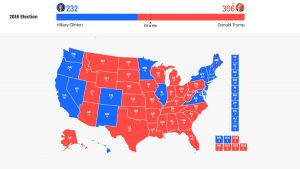

A case of ideology polarisation, the US 2016 election fake news was a sensation. To everyone’s surprise, the populist candidate Donald Trump was elected President of the United States after a close race. During the presidential campaign, fake news, deliberate and falsifiable news articles, were prevalent on Facebook (Allcott, 2017). A study after the election showed that the hottest fake news stories on Facebook gained even more attention than the major news media in the last three months before the election (Silverman, 2016). Moreover, according to the data, these fake news stories heavily favored Trump, with 115 fake news stories about Trump receiving over thirty million shares. In comparison, 41 fake news stories about Clinton only received around 7.6 million shares (Allcott, 2017). As a result, explanations about social media shaping users’ filter bubbles through algorithms to help Trump win have gone viral, and this claim is not an empty one.

Collinson, S. (2020). Watch these nine states in the US election. [Download Image].

Facebook’s algorithmic delivery of filtered news to its users is a feature that has been in place for a long time. News Feed is a news access channel for Facebook users that has existed since 2006, and the software has been algorithmically reducing the appearance of politically challenging views to its users (Dylko, 2017). According to Jacobson’s research, 80% of news references for news audiences of both parties occupy just a third of the total information resources (2016). Along with narrow horizons, social media’s lowering of the creative bar leads to a hostile and misinformation-prone discussion environment that reinforces users’ views (Groshek, 2017). Furthermore, users whose ideologies are already at an extreme state will actively use personalization to shape the filter bubble. However, moderate users at the neutral end of the spectrum begin to gain significantly less access to opposing viewpoints after exposure to personalization and form filter bubbles (Dylko, 2017). As a populist, Trump can be significantly helped by the ideology polarization brought about by the filter bubble. Shaping users’ filter bubbles by social media through fake news contributed significantly to Trump’s election.

However, although social media has directly or indirectly nurtured populists who support Trump through filter bubbles, his success cannot be said to be entirely dependent on this. It also counts on Trump’s various offline campaigns and ad placements. Moreover, it is not only the filter bubbles that polarise users’ ideology on social media but also selective exposure.

Critical on Filter Bubble

Selective exposure is different from the polarization caused by filter bubbles by algorithms, which describe user psychology. It can be defined as the preference of users to consume media with which they share an opinion to avoid having their position challenged (Spohr, 2017). Unlike algorithmic personalization or pre-determined personalization of the filter bubble, it is self-selected personalization that causes selective exposure. On the other hand, algorithms augment this personal personalization, such as Facebook’s powerful algorithms, allowing users to filter information more efficiently and gain selective enhancements. However, the filter bubble can also be seen as an enabler of selective exposure. Despite the strong selective exposure of Facebook users, user-driven personalization has a slightly lesser impact on selective exposure than system-driven personalization (e.g., News Feed and filter bubbles) (Dylko, 2017). Filter bubbles and selective exposure are sometimes not entirely viewed as unrelated concepts.

Filter bubble has also been criticized for many reasons other than the suspicion brought by selective exposure. Firstly, as the person who proposed the concept, Pariser did not provide a clear definition for it but instead used anecdotes to interpret the concept (Bruns, 2019). The ambiguity of the concept has undoubtedly created a hindrance to subsequent scholarship.

Sweet, K. (2019). Personalization Defined: What is Personalization?. [Download Image].

Secondly, filter bubbles, as well as personalization, are not all bad. As previously mentioned, users in the Web 2.0 era have richer access to information. Personalization and filter bubbles can be seen as tools that can effectively help users cope with information overload and efficiently access information that reinforces their attitudes (Dylko 2017). Even in a sense, filter bubbles and personalization can be beneficial in many cases. On the one hand, it allows groups holding the same interests to communicate online at any given time and share information with the group as a whole; on the other hand, it can help minorities and disadvantaged groups in society to support each other (Helberger 2019).

It is biased to blame all the causes of ideology polarisation on the filter bubbles, as the filter bubbles themselves also have a beneficial side and may lead to the neglect of other core issues such as selective exposure.

How to Fight Against Filter Bubble

Although the filter bubble has its benefit, it is still critical to know how to counteract them, given that it is still an essential factor in the polarization of ideology. The impact of filter bubbles on the polarisation of ideology is expected to increase with the growth of social media.

From the perspective of individual citizens, users should develop a sense of active news and information consumption, actively seeking out diverse and high-quality information rather than passively waiting for recommendations from social media platforms (Spohr, 2017) to combat filter bubbles.

From the perspective of algorithmic technology, firstly, algorithms should be redesigned to reduce the likelihood of filter bubbles, for example, by introducing the ability for users to be invisible online or not to keep browsing history to stop social media from tracking user data. Social media such as Facebook and Google have also introduced fact-checking agencies and flagged false content in their software (DiFranzo, 2017). Secondly, companies such as Facebook, Google, and others need to acknowledge and take corporate responsibility in the management of information that has the potential to create filter bubbles such as fake news. They have a history of blurring the lines between themselves as technology companies and media companies to avoid taking responsibility (Levin, 2018). Going further, it is also possible to actively seek cooperation with governments to introduce effective policies on fake news.

Finally, from a societal perspective, good civic character building, such as the cultivation of civic virtues, can effectively counter the individualism that comes with a filter bubble. This virtue is a willingness to act for the benefit of something other than oneself and the ability to think differently and ethically for others and even society (Pratte, 1988).

Hess, A. (2017). How to Escape Your Political Bubble for a Clearer View. [Download Image].

Conclusion

Overall, filter bubbles have had a profound impact on ideology polarisation. The personalization of social media is an important reason for forming filter bubbles. At the same time, misinformation such as fake news can act as a filter bubble booster to push the ideology polarisation process forward. This can also be derived from the fake Facebook news in the US 2016 election. However, filter bubbles are only one of the factors that influence the polarisation of ideology. Not only are there other important factors, such as selective exposure, but filter bubbles have also been criticized for their vague definition. In order to combat filter bubbles, it is vital that users actively access quality information on an individual level, that companies such as Facebook promote algorithm updates and take responsibility for them, and that society tries to cultivate civic virtue. In the Web 2.0 era, social media users should take the best of filter bubbles, remove the worst, and enrich themselves with a diverse range of information to avoid ideology polarisation. In this way, users can contribute to a better online community in this era.

(Word count: 2050)

Reference List:

- Andrejevic. (2019). Chapter 3: Automated Culture, pp 44-72. Automated Media. Routledge.

- Allcott, & Gentzkow, M. (2017). Social Media and Fake News in the 2016 Election. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 31(2), 211–235. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.31.2.211

- Baehr, & Lang, S. M. (2012). Hypertext Theory: Rethinking and Reformulating What We Know, Web 2.0. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 42(1), 39–56. https://doi.org/10.2190/TW.42.1.d

- Bruns. (2019). Filter bubble. Internet Policy Review, 8(4). https://doi.org/10.14763/2019.4.1426

- Dylko, Dolgov, I., Hoffman, W., Eckhart, N., Molina, M., & Aaziz, O. (2017). The dark side of technology: An experimental investigation of the influence of customizability technology on online political selective exposure. Computers in Human Behavior, 73, 181–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.03.031

- DiFranzo, & Gloria-Garcia, K. (2017). Filter bubbles and fake news. Crossroads (Association for Computing Machinery), 23(3), 32–35. https://doi.org/10.1145/3055153

- Groshek, & Koc-Michalska, K. (2017). Helping populism win? Social media use, filter bubbles, and support for populist presidential candidates in the 2016 US election campaign. Information, Communication & Society, 20(9), 1389–1407. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2017.1329334

- Gottfried, J, Shearer, E (2016) News use across social media platforms 2016. Pew Research Center. Available at: http://www.journalism.org/2016/05/26/news-use-across-socialmedia-platforms-2016/

- Helberger. (2019). On the Democratic Role of News Recommenders. Digital Journalism, 7(8), 993–1012. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2019.1623700

- Jacobson, Myung, E., & Johnson, S. L. (2016). Open media or echo chamber: the use of links in audience discussions on the Facebook Pages of partisan news organizations. Information, Communication & Society, 19(7), 875–891. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2015.1064461

- Levin, S. (2018). Is Facebook a publisher? In public it says no, but in court it says yes. The Guardian. Retrieved from: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2018/jul/02/facebook-mark-zuckerberg-platform-publisher-lawsuit

- Mervis. (2014). Social Science. An Internet research project draws conservative ire. Science (American Association for the Advancement of Science), 346(6210), 686–687. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.346.6210.686

- Nikolov, Oliveira, D. F. M., Flammini, A., & Menczer, F. (2015). Measuring online social bubbles. PeerJ. Computer Science, 1, e38–. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.38

- Pariser E. (2011). The filter bubble: how the new personalized Web is changing what we read and how we think . London: Penguin, 2011.

- Pew Research Center. (2014). Political Polarization in the American Public. http://www.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2014/06/6-12-2014-Political-Polarization-Release.pdf.

- Pratte. (1988). Civic education in a democracy. Theory into Practice, 27(4), 303–308. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405848809543369

- Pariser. (2011). The filter bubble : what the Internet is hiding from you. Viking.

- Spohr. (2017). Fake news and ideological polarization: Filter bubbles and selective exposure on social media. Business Information Review, 34(3), 150–160. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266382117722446

- Silverman, C (2016) This Analysis Shows How Viral Fake Election News Stories Outperformed Real News On Facebook. BuzzFeed News. Retrieved from: https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/craigsilverman/viral-fake-election-news-outperformed-real-news-on-facebook#.hr0DxG49r

- Sunstein. (2001). Republic.com. Princeton University Press.

- Zuiderveen Borgesius, Trilling, D., Möller, J., Bodó, B., de Vreese, C. ., & Helberger, N. (2016). Should We Worry about Filter Bubbles? Internet Policy Review, 5(1). https://doi.org/10.14763/2016.1.401

Image Reference

- Collinson, S. (2020). Watch these nine states in the US election. [Download Image]. Retrieved from: https://edition.cnn.com/2020/10/19/world/meanwhile-in-america-october-19/index.html

- Hess, A. (2017). How to Escape Your Political Bubble for a Clearer View. [Download Image]. Retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/03/03/arts/the-battle-over-your-political-bubble.html

- ResearchGate. Predictive Modeling Approach for Filter Bubble Bursting. [Download Image]. Retrieved from: https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Predictive-modeling-approach-for-filter-bubble-bursting_fig4_334753095

- Sweet, K. (2019). Personalization Defined: What is Personalization?. [Download Image]. Retrieved from: https://www.business2community.com/marketing/personalization-defined-what-is-personalization-02178138

- Shishi, F. (2021). It’s Time to Pop China’s Online Filter Bubbles. [Download Image]. Retrieved from: https://www.sixthtone.com/news/1006664/its-time-to-pop-chinas-online-filter-bubbles