Introduction:

As network technology improves by leaps and bounds, there are many online social media platforms such as TikTok, YouTube and Facebook which have become indispensable tools to bring benefits and convenience to people’s daily life. At the same time, the spread of fake news, misinformation and disinformation on the digital platform has also aroused social concern.

This is caused by the era of big data used in those platforms. Algorithms and algorithmic selection are inevitable outcomes of the big data revolution because of the improvement of computational power and the great mountains of data that can be used in the process (Flew, 2021). In this process, the algorithm iteratively, automatically and statistically evaluates a large and diverse amount of data from users’ interactions on the web (user inputs) to more accurately predict the relevant information (outputs) sought by the user (Just & Latzer, 2017; Flew, 2021). These information are not only the content that users might like, but also are a mix of true and fake news that might have an influence on the security and stability of society. This blog will first take TikTok as an example to introduce the platform’s policy of “combating disinformation” in response to the Russia-Ukraine war and show the subsequent cases of war-related disinformation in TikTok, and then analyze the fake news under the algorithmic age. Finally, the discussion of algorithmic governance will be explored by taking China as an example.

(Figure from The Telegraph. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/world-news/2022/01/29/russia-ukraine-crisis-will-first-tiktok-war/)

(Figure from The Telegraph. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/world-news/2022/01/29/russia-ukraine-crisis-will-first-tiktok-war/)

TikTok case study- fake news in the Russia-Ukraine war:

1-New protective measures of TikTok toward the Russia-Ukraine war

TikTok (2022), which is a popular social media platform, on March 5 – the tenth day of the Russian-Ukraine war, took a number of measures to the platform’s use of algorithms, the second of which was to “Combatting misinformation” and to state that the platform would prohibit content containing hateful acts, harmful misinformation or promoting violence, and would remove those offending content at the same time. In addition, the platform will not recommend content that has not been verified to the users’ FOR YOU feeds. Meanwhile, given Russia’s new “fake news” law, the platform has announced the suspension of its services in Russia (new content for live streams and videos), preventing TikTok users in Russia from seeing any content posted by accounts outside the country. In fact, TikTok has “turned a blind eye” to the policy of “combating disinformation”.

(Figure from South China Morning Post. https://www.scmp.com/tech/big-tech/article/3167797/tiktok-said-restore-russian-media-account-video-ukraine-crisis-after)

(Figure from South China Morning Post. https://www.scmp.com/tech/big-tech/article/3167797/tiktok-said-restore-russian-media-account-video-ukraine-crisis-after)

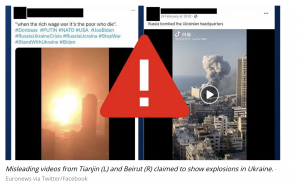

2-Fake news still circulated by the algorithm on Tik Tok

A study demonstrates TikTok’s reticence towards the second policy. 2022 In March, six NewsGuard analysts from Switzerland, Germany, Italy, the UK and the US registered new accounts on TikTok and conducted experiments. They first found that in the absence of any search and the act of following any account, within 40 minutes of a user’s registration, the platform provided all analysts’ new accounts with false and misleading content about the war in Ukraine, without indication of false information and reliable sources (Cadier et al., 2022). The content is both pro-Russian and pro-Ukrainian, e.g., footage of Ukrainian President Zelensky “fighting for his country” was actually filmed in 2021; footage of the “Ghost of Kyiv” shooting down six Russian jets, which was actually taken from a video game–Digital Combat Simulator…In Euronews, A misleading video about Ukrainian armed forces storming the streets of Mariupol has amassed over 3 million views on TikTok. However, the fact is that the video was first posted during the pro-Russian separatist crisis in 2014 (The Cube. 2020) (Figure 1). Another disinformation even uses a video of a warehouse explosion in Tianjin, China, to create misleading information (Holroyd, 2022) (Figure 2).

(Figure 1 form Euronews. https://www.euronews.com/my-europe/2022/03/22/new-tiktok-users-exposed-to-fake-news-about-russia-ukraine-war-study-reveals)

(Figure 1 form Euronews. https://www.euronews.com/my-europe/2022/03/22/new-tiktok-users-exposed-to-fake-news-about-russia-ukraine-war-study-reveals)

(Figure 2 form Euronews. https://www.euronews.com/my-europe/2022/03/15/debunking-the-viral-misinformation-about-russia-s-war-in-ukraine-that-is-still-being-share)

(Figure 2 form Euronews. https://www.euronews.com/my-europe/2022/03/15/debunking-the-viral-misinformation-about-russia-s-war-in-ukraine-that-is-still-being-share)

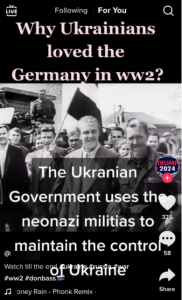

In addition, NewsGuard analysts searched for general information about the conflict that might use these terms, such as Russia, Ukraine, Donbas, Kyiv and war. In the videos suggested by the TikTok search algorithm, the top 20 results included false or misleading content. For example, when searching for the keyword “Donbas”, a video about the claim that neo-Nazis are “everywhere” in Ukraine and that “the Ukrainian government uses neo-Nazi militias to maintain control of Ukraine” appeared in the fifth recommended video of an analyst’s findings, and the content of the video appeared without any specific factual basis.

(Figure from NewsGuard. https://www.newsguardtech.com/misinformation-monitor/march-2022/)

(Figure from NewsGuard. https://www.newsguardtech.com/misinformation-monitor/march-2022/)

Furthermore, in another study initiated by the social media research collective Tracking Exposed (2022) into TikTok’s algorithmic adjustment of banned content to Russia, it was shown that restrictions of TikTok on the Ukraine-Russian war are beyond the requirements of responding to Russia’s “fake news” law, and the limitation for Russian users is wrapping them in a giant echo chamber to appease president Vladimir Putin’s government by exposing them only to Russian propaganda that supports the war. Finally, the study claims that it is unprecedented for a global social platform to take large-scale restrictions against the country, and the motives of TikTok are not clear. These behaviours of TikTok make the public more curious about the application and management of its powerful and influential algorithm.

(Figure from Michalsons. https://www.michalsons.com/focus-areas/robot-law/algorithm-law-governance-and-compliance)

(Figure from Michalsons. https://www.michalsons.com/focus-areas/robot-law/algorithm-law-governance-and-compliance)

Analyze the TikTok case under the algorithmic age:

TikTok has a huge number of users, overtaking Facebook in 2021 to become the first application with more than one billion monthly users (Tik Tok, 2021), while in the latest State of Mobile Devices 2021 report it was found that people are more likely to spend more time on Tik Tok (20 hours in 2020) than on Facebook (16 hours in 2020) (Alonso López et al., 2021). Behind this is its powerful algorithm system, which is “stirring” the war in a “black box” way.

In violation of its commitment to “combatting disinformation”, TikTok blocks content in Russia, while using itself as one of the “information warfare bases” to provide users with false and misleading videos about the Russian-Ukrainian war through its algorithms, even suggesting such videos to new users without any user history. The use of algorithms by TikTok company will bring challenges to society and individuals. From a social perspective, TikTok, which has great self-determination, proactivity, and the pathological customized curation of the algorithm’s goal, can not only be “unaccountable” for its promises, but also manipulate the algorithm to control content in Russia, and finally, the pathological algorithmic system controls what users are going to see, prioritizing the distribution of polarizing, false, political and controversial information sent to their pages (Andrejevic, 2019). Not only is there no purposeful misinformation in this content, but there is also disinformation with a political propaganda purpose (containing pro-Ukrainian and pro-Russian content) (Benkler et al., cited in Flew, 2021), which might be weaponized by some parties to increase opinion polarization and political polarization, incite war sentiments, add fuel to the war, and cause more severe damage. From the user’s perspective, TikTok’s automated algorithmic selection shapes the “reality” and “lives” of its users, influencing their perceptions and behaviours in the world, and consuming them physically and mentally as well. The social platform not only provides users with a filter bubble that can narrow the scope of recommended content to reinforce their existing opinions and prejudices (Flew, 2021; Pariser, 2011), but also tries to actively expand users’ original filter bubble by pushing new content (such as knowledge in other fields and controversial information) that users might be eager to spend time and energy to browse. As in the example of TikTok, the algorithm draws users’ attention, passion, and anger to “fake news” of the war, while also consuming their attention to resources in other areas of their lives (Burkeman, cited in Andrejevic, 2019) and bringing them with negative emotions.

However, it is difficult to understand the secrets of the algorithm in TikTok. Unlike Twitter and Mate, there is little relevant research on Tik Tok. In 2019, for the spread of Covid-19 misinformation and research of online manipulation activities related to governments such as Russia, China and Mexico, in addition to Tik Tok, both Twitter and Mate provide APIs (Application Programming Interfaces) for researchers to help them analyze information circulation on the platforms (Simonite, 2022). Tik Tok’s “secretive” behaviour hides the algorithms deep in an opaque, complex and impenetrable black box that is hard to delve into (Flew, 2021).

The discussion of algorithmic governance:

the workings of TikTok’s powerful algorithmic mechanism are difficult to understand. Just as other internet giants claim that their algorithms are scientific and neutral, such claims are difficult to substantiate (Pasquale, 2015). However, the resulting growing phenomenon of fake news needs to be governed by means such as recalibrating the performance of algorithms by technology companies, and active improvement of netizens’ personal civic literacy, identity awareness and cognitive mode (Andrejevic, 2019); limiting the power of algorithms to the purpose of promoting fairness, freedom and rationality (Pasquale, 2015); creating systems to alert the public and to help netizens identify types of news (Tiwari et al., 2020); implement public policies to legitimize the governance of algorithmic disorder (Just & Latzer, 2017), and so on.

(Figure from CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com/2021/09/03/chinas-tech-regulation-turns-to-algorithms.html)

(Figure from CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com/2021/09/03/chinas-tech-regulation-turns-to-algorithms.html)

On 1 March 2022, Chinese authority took the lead in promulgating and implementing the Regulations on the Administration of Algorithm Recommendations for Internet Information Services (2022), which broadly addresses the abuse of algorithms and gives users the option to turn off algorithm recommendations so that they are no longer passively controlled by algorithms. For fake news in the context of algorithms, the regulations make the following provisions: Article 13: Algorithms shall not generate synthetic and disseminate fake news information…; Article 14: Algorithms shall not be used to falsely register accounts, illegally trade accounts, manipulate user accounts or falsely like, comment on or share them, or use algorithms to block information, over-recommend…or sort search results, control hot Search and other interference with the presentation of information… This not only helps internet users avoid news that is difficult to trace back to the source and distinguish the authenticity of the news, but also counteracts the phenomenon of algorithms maliciously pushing controversial fake news, which facilitates more real-world exposure to users on social media, while also relatively moderating the development of opinion and political polarization. However, this governance also raises further questions. Although it is too early to explore how the effects of implementing the regulations will be, does it raise other questions: is it possible that a more comprehensive policy to regulate algorithms could also have constraints on the innovation and economy of technology companies? Could this in turn have an impact on the creativity and economic development of society?

Conclusion:

The spreading of fake news on TikTok about the Russia-Ukraine war and the blocking of news in Russia show that technology companies have great power in the application of algorithms, and also demonstrate the increasingly serious emergence of fake news in the algorithmic era. Those “news” are not only false and misleading in terms of content, but also distributed in deliberate ways, which means that it is pushed directly to users’ pages through algorithms without relying on their personal data. These phenomena have a negative impact on the physical and mental health of individuals, and also on the stability and solidarity of societies, even causing social divisions and international conflicts. Therefore, the rational governance of algorithms is an important issue that needs to be considered. There are many types of measures that can be done in terms of public policy, technology companies, individual internet users and so forth. China is comparatively leading in governing algorithms through legislative regulations, which serves as an attempt to manage the algorithm through public policy, and also has reference significance for establishing human-centered operation of algorithms in the future. However, it still needs time to discuss whether an effective regulation algorithm can be adopted after the implementation. Therefore, there is still a long way to go for algorithm governance.

Reference:

Alonso López, N., Sidorenko Bautista, P., & Giacomelli, F. (2021). Beyond challenges and viral dance moves: TikTok as a vehicle for disinformation and fact-checking in Spain, Portugal, Brazil, and the USA.

Andrejevic, M. (2019). Automated Culture, in Automated Media. London: Routledge, pp. 44-72.

Cadier, A., Labbé, C., Padovese, V., Pozzi, G., Badilini, S., Schmid, R., Roache, M., & Brewster, J. (2022). WarTok: TikTok is feeding war disinformation to new users within minutes — even if they don’t search for Ukraine-related content. Retrieved from NewsGuard website: https://www.newsguardtech.com/misinformation-monitor/march-2022/

Cyberspace Administration of China (2022). Regulations on the Administration of Algorithm Recommendations for Internet Information Services. Retrieved January 3, 2022, from http://www.cac.gov.cn/2022-01/04/c_1642894606364259.htm

Flew, T. (2021). Regulating platforms. Cambridge, UK;: Polity Press.

Holroyd, M. (2022). Debunking the most viral misinformation about Russia’s war in Ukraine. Retrieved from Euronews website: https://www.euronews.com/my-europe/2022/03/15/debunking-the-viral-misinformation-about-russia-s-war-in-ukraine-that-is-still-being-share

Just, N., & Latzer, M. (2017). Governance by algorithms: reality construction by algorithmic selection on the Internet. Media, Culture & Society, 39(2), 238–258. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443716643157

Pariser, E. (2011). The Filter Bubble: What the Internet is Hiding From You. New York, NY: Penguin Press.

Pasquale, F. (2015). The Need to Know, in The Black Box Society: The Secret Algorithms That Control Money and Information. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, pp.1-18.

Simonite, T. (2022). TikTok’s Black Box Obscures Its Role in Russia’s War

Retrieved from Wired website: https://www.wired.com/story/tiktok-algorithm-russia-war/

The Cube. (2022). New TikTok users exposed to fake news about Russia-Ukraine war, study reveals. Retrieved from Euronews website: https://www.euronews.com/my-europe/2022/03/22/new-tiktok-users-exposed-to-fake-news-about-russia-ukraine-war-study-reveals

Tik Tok. (2021). Thanks a billion!. Retrieved September 27, 2021, from https://newsroom.tiktok.com/en-us/1-billion-people-on-tiktok

Tik Tok. (2022). Bringing more context to content on TikTok. Retrieved March 5, 2022, from https://newsroom.tiktok.com/en-us/bringing-more-context-to-content-on-tiktok

Tiwari, V., Lennon, R. G., & Dowling, T. (2020). Not Everything You Read Is True! Fake News Detection using Machine learning Algorithms. 2020 31st Irish Signals and Systems Conference (ISSC), 1–4. IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ISSC49989.2020.9180206

Tracking Exposed. (2022). Tracking Exposed Special Report: TikTok content restriction in Russia. Retrieved March 15, 2022, from https://tracking.exposed/pdf/tiktok-russia-15march2022.pdf