Introduction

The Internet has been successful because it eliminates distance, breaks down real-world barriers of time and geography, and allows for global, interactive information transmission. Since its inception, the Internet has emphasized freedom of expression as a fundamental right and opposed government regulation and censorship of Internet content. From a time when the Internet was only a tool used by a small group of technology enthusiasts to communicate, it has become an everyday use for billions of people around the world. The impact of the Internet has also changed dramatically.

However, at present, there is still no unified definition of online hate speech. Different researchers, governments, non-government organisations (NGOs) and platforms have different definitions of online hate speech. This has resulted in a number of subset concepts, each attempting to distinguish between defining more narrowly online hate behaviours (Pohjonen, 2019). For example, online hate speech was defined by Anti-Defamation League “any use of electronic communications technology to spread anti-Semitic, racist, bigoted, extremist or terrorist messages or information.” (ADL, 2010, p. 1). However, the definition of online hate speech in the European Union legislation is more oriented towards violence and hatred motivated by racial discrimination (European Commission, 2008).

But the current research does not prove that online hate speech is absolute related to violence incident. But in many cases, the public should be aware of the serious impact on normal life of online hate speech. Terry Flew’s (2021) section about hate speech and Online Abuse in Regulating Platforms also explicitly mentions the effects of online hate speech amplified by social media, including physical threats, harassment over a sustained period, stalking, and so on. He also mentions the large number of innocent people who have been injured or killed because of online hate speech. This blog will discuss the case of a young man who committed suicide as a result of online hate speech to clarify the reality of the harm caused by online hate speech. We will discuss the impact of the anonymity of the internet and user-generated content (UGC) on online hate speech, from how cyber violence is formed to why it is difficult to control. I will also discuss how the Chinese government, platforms and other organizations are trying to combat these problems.

Why is there so much online hate speech?

The Internet has become an important tool for global communication and transmission, with a huge amount of data being generated and communicated on the Internet every hour of every day, Hundreds of hours of video content are uploaded every minute on YouTube. This enormous amount of online content forms the basis of the Internet. The online content usually simply separates into two kinds, one is the content created and communicated by traditional publishers into the online space, such as the New York Times website and its Facebook account. The other kind is user-generated content (UGC) (Roberts, 2017). But with the explosion of the online community and the rise of social media platforms, the distinction between these two kinds has become much blurred, and massive amounts of lies, fake news and bogus messages have taken the opportunity to enter this mess. Users tend to engage with and amplify content that is intended to be sensational, provocative or misleading (Zuckerberg, 2018). Thus on the platform these provocative content is more popular, which also inspires the creation of online hate speech. Most users on social platforms generally want to receive a response, to gain acceptance and a sense of belonging, and the easiest way to get that is to make a moral condemnation. It becomes a kind of reward for online hate speech, and other users will make similar speech when they saw it, so it becomes a habit to attack others at will on the internet (Crockett, 2017). And the anonymity of the Internet provides perfect protection for these people from any fear or liability. While Zimbardo (1969) describes this anonymity in virtual worlds as “deindividuation theory”. According to this theory, as long as other people are unable to identify this person as an individual, it is difficult to develop guilt, shame and fear, which can also lead to more online violence and even to violence in real life. Anonymity on the Internet also dilutes the sense of social belonging of other users, which leads to more people standing away. This is almost the worst possible outcome for victims of online violence, with few people willing to offer useful help, while the volume of hate speech is enormous. The anonymity is also a major factor that is difficult to resolve with online hate speech, as online violence is almost invisible to everyone, and when you try to fight it back, the perpetrators don’t leave any information except the attack, and they can easily delete what they have posted so that there is no evidence to accuse them. Moreover, in most cases this will involve many people, most of them do not know the facts and just follow the comments, making it impossible to assign responsibility.

Figure 1. “On the Internet, nobody knows you’re a dog” form The New Yorker

As a general word, the concept of online hate speech is too wide, some of them just minor arguments, but some may serious discrimination and threats, even resulting in cases of intentional injury or murder. We need to know some of the types of online hate speech that can be subdivided, such as verbal attacks, disinformation and harassment, cyber manhunt and exposure of private information (William & Guerra, 2007). All of these actions can have an unknown impact on real life. When those who spread hate on the internet have your personal information, it can cause you enormous trouble. You may be criticised on the road, have rubbish dumped on your doorstep, or even be harassed at midnight. In this case online hate speech should be taken seriously as a crime.

Boy suicides because of hate speech on Weibo

Just recently, Liu Xuezhou, a 15-year-old boy chose suicide under the influence of online violence. This boy was abandoned by his parents at birth, and his adoptive parents died accidentally when he was four and he was bullied at school because of all this. He made many efforts to eventually find his biological parents, however this is not an ideal fairy tale. His biological parents did not want to accept him and he posted his difficulties on Weibo hoping to get some help and advice. But he has received countless misunderstandings, accusations and insults. People on the platform accused him of using his tragic story to gain social attention just want to be famous. He was misunderstood to have used the internet to force his parents to buy a house. Abuse was hurled at him for taking the blame for everything. In the end, the boy chose to end his life on the twenty-ninth day after he found his biological parents after all his trials and tribulations. This is not the first time that something like this tragic incident has happened, not only in China, but all over the world, where many young people have chosen to commit suicide after experiencing the effects of online hate speech. This is something we need to take seriously. In addition to these cases leading to death, there are many more situations that give rise to other harmful behaviour, such as stalking and harassment.

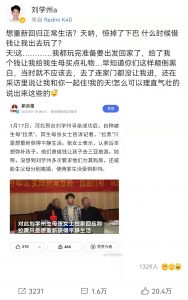

There is also a major participant in this incident, which is the Beijing News, and it is now widely considered on the internet that its exclusive interview with Liu’s parents was the source of the rumours and online brutality. Even though the Beijing News removed the news article quickly after Liu’s suicide, we can still see a screenshot of this article in Liu’s Weibo account. The picture in this Weibo from Liu’s account shows a separate interview with Liu’s biological mother, who claims that she borrowed money to allow Liu travel and that Liu threatened his biological parents asking them to buy property for him. Liu’s Weibo post delivered a rebuttal, saying that his biological mother only gave him money to bring some gifts, and that his biological mother didn’t even let himself into the house, but created rumours that he was living with them. Despite both of the sides had their own arguments, the Beijing News only reported Liu’s mother’s arguments, which led to a large number of users who were unclear about the incident to engage in online brutality against Liu.

Figure 2. Weibo from Liu Xuezhou about Beijing news article

Some possible solutions

Despite the fact that these terrible social incidents have taken place. But as we look back on these incidents, we have to admit that it is impossible to prevent online hate speech, whether by organisations or governments. Even after these incidents, we are still in the initial stages of exploring how to define responsibility and how to punish those who bully. We would like to discuss solutions in two of the most productive directions, the first is governmental regulations and the second is functional improvements of the platform.

In 2021, China launched a special campaign to clear the Internet, mainly targeting accounts that maliciously attacked other users and blocking them, disposing of 1.34 billion accounts that violated the regulations and dealing with 22 million posts involving false information and undesirable information (Sibei, 2022). The main purpose of this operation was to deal with the large number of web bots and companies that use these bots to guide their comments on the posts. The Chinese government also began enacting a law in 2013 “to clarify that those who use the Internet to abuse and intimidate others, disrupt the social order and cause bad influence will be punished for the crime of picking quarrels and provoking trouble.” However, most of the provisions of this policy do not have clear and quantifiable indicators, and most of these can only be used to punish the promoters of online hate speech, while the large number of rabble-rousers cannot be effectively regulated.

Compared to the government’s use of laws to punish, platforms do not have heavy penalties, but they do have more specific data. The platform’s extensive database also allows for the retention of evidence and provides for government penalties. Social media platforms are highly visible, content can be easily and quickly shared with large numbers of users, and hate speech can have long-lasting effects if not effectively removed (Rudnicki & Steiger, 2020, p44). The best solution for the platform is to quickly protect users from online hate speech. Douban, a Chinese social media platform was recently updated with an emergency protection model. When this mode is switched on, other users cannot follow, interact or private message without permission. All comments containing unfriendly keywords in posts by users with protected mode on will be hidden and all posts cannot be reposted or favourited (Douban, 2022). Although these policies do not completely eliminate the damage of online hate speech, they do protect all users in some way.

Conclusion

Through these social incidents caused by online hate speech, we will find that a large number of users and some media with ulterior motives are only concerned with flow and fame, and do not care about the serious consequences caused to others. Due to the anonymity of the internet, lots of users transfer their stress to others through online hate speech, attracting more attention through hate speech. Because of the technical limitations of the internet, it is impossible for either the government or the platform to end the harmful effects of online hate speech. From the point as a government, From the government’s point of view, on the one hand, there is a need to create a more comprehensive and specific legal system adapted to the characteristics of the Internet to establish a system of punishment, so that cyberbullies can be severely punished. On the other hand, the government needs to strengthen propaganda and education so that the public is aware of the serious implications and consequences of online hate speech for individuals and society. It is of utmost urgency for platforms to establish proper accountability and to strengthen the protection of personal information and privacy of all users. Especially with the large number of teenagers on social media platforms, the impact of Online hate speech on these young people could have unimaginable consequences. We do not want to see such a tragedy happen again.

Just as I write this blog, In Shanghai under the lockdown of the COVID-19. A young girl was attacked with online brutality because she gave a delivery boy a 200-yuan reward. Under heavy pressure, she chose to end her life. It Is too late to say we can give some help, R.I.P.

Reference list

ADL (2010). Responding to Cyber hate. Toolkit for Action. Anti Defamation League, http://www.adl.org/assets/pdf/ combating-hate/ADL-Responding-to-CyberhateToolkit.pdf.

Crockett, M. . (2017). Moral outrage in the digital age. Nature Human Behaviour, 1(11), 769–771. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-017-0213-3

Douban. (2022). Douban Use Agreement & Douban Personal Information Protection Policy. Retrieved from https://accounts.douban.com/passport/agreement

European Commission (2008, November 28). Framework Decision on combating certain forms and expressions of racism and xenophobia by means of criminal law (Framework Decision 2008/913/JHA). Retrieved from: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=LEGISSUM%3Al33178

Flew, T. (2021) Regulating Platforms. Cambridge: Polity, pp. 91-96.

Pohjonen. (2019). A Comparative Approach to Social Media Extreme Speech: Online Hate Speech as Media Commentary. International Journal of Communication (Online).

Roberts S.T. (2017) Content Moderation. In: Schintler L., McNeely C. (eds) Encyclopedia of Big Data. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-32001-4_44-1

Rudnicki, K. , & Steiger, S. . (2020). Online hate speech – Introduction into motivational causes, effects and regulatory contexts.

Sibei Wang. (2022, March 17). 1.34 billion accounts to be disposed of in 2021 in “Qinglang” series of special operations. Xinhuanet. Retrieved from http://www.news.cn/2022-03/17/c_1128479272.htm

The Supreme People’s Procuratorate of the People’s Republic of China. (2013, September 10). Explanations on Several Issues Concerning the Application of Law in Handling Criminal Cases of Internet Defamation, etc. issued by The Supreme People’s Procuratorate of the People’s Republic of China and The Supreme People’s Court of The People’s Republic of China. Retrieved from https://www.spp.gov.cn/zdgz/201309/t20130910_62417.shtml

Williams, K. R., & Guerra, N. G. (2007). Prevalence and Predictors of Internet Bullying. Journal of Adolescent Health, 41(6), S14–S21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.08.018

Xuezhou, Liu. [Liu Xuezhou a]. (2022, January 19). Want to get back to a normal life? [Weibo]. Retrieved from https://m.weibo.cn/6275961723/4727343714929605

Zimbardo, P. G. (1969). The human choice: Individuation, reason, and order, vs deindividuation, impulse, and chaos ‘, in Wj Arnold and D. Levine (eds) Nebraska Symposium on Motivation 1969. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.

Zuckerberg, M. (2018, November 15). A blueprint for content governance and enforcement. [Facebook]. Retrieved from https://www.facebook.com/notes/751449002072082/