Introduction

With the blooming of the digital economy and the development of digital technology, the internet and smart devices have fully entered our lives which made increasing numbers of people become the audiences of the internet. Between 2016 to 2020, internet usage increased by 30%. The powerful functions and customized services on the internet have made us gradually become more dependent on it. Especially under the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic, more people start to move their activities from offline to online, which led to a surge in online traffic and increased tracking on commercial and public internet platforms and websites (Yaraghi & Lai, 2022). While the internet and digital technology help public and government development better, it also means that more data-related issues will come out to our attention.

As most developed and developing countries realize the future of smart cities, it is clear that the digital tracking approach is a more efficient option when it comes to COVID-19. In this case, there are many countries around the world have already adopted this approach to epidemic prevention and management. This is beneficial for managing national epidemics as well as for developing high-tech medical industries. However, it poses a threat to users’ data. The tracking application will record the user’s personal information and do the personal data collection, including their daily movements and contacts with people, in detail. When there is no authority organization that can implement the responsibility of users’ data protection, once collected data is misused by the government or third party organizations, it will not only bring a negative influence on users’ privacy safety but also lead to a crisis of trust between public and government.

Therefore, this blog will focus on the concerns about the misuse of personal data in a digital age under the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic with majorly discussing the misuse of contact tracking data issued by the Trace Together application and the Singapore government.

The TraceTogether Application Misuse of Contact Privacy Issue

Under the influence of COVID – 19 pandemics, Singapore decided to adopt digital contact tracing tools – TraceTogether (TT) and SafeEntry as the COVID -19 digital management solution to achieve potential virus carrier tracking and virus ringfence work. Among them, the TraceTogether Programme was developed by the Government Technology Agency of Singapore (Gov Tech) which can track interactions between people diagnosed with coronavirus and those they have met. The goal is to effectively isolate people in the broader community who may have unknowingly contracted the virus (Lee & Lee, 2020). Due to the limitations of Bluetooth signals on cell phones, they also launched TraceTogether Token to serve users who do not use smartphones. Users only need to carry it with them, and the token will work for outbreak prevention and control.

In the beginning, the Singapore government claimed that the collected data would only be used for coronavirus management with no mention of if the data would be sent to national institutions for wider surveillance usage. They also emphasize that this app will never collect users’ location information. Only if users got positive coronavirus test results and contact the tracing team, they will never access users’ data. Additionally, they claim that the collected data will be deleted once the COVID – 19 pandemic ends.

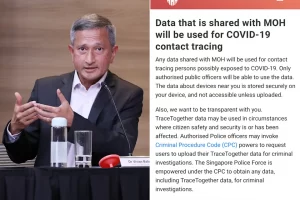

However, in January 2021, Desmond Tan, the Minister of State at the Ministry of Home Affairs said that the police were capable to access the TraceTogether data for criminal investigations. After that, the privacy statement on the TraceTogether website which previously indicated that “the collected data will only be used for contact tracing of persons possibly exposed to COVID – 19”, was modified immediately. Based on the report from Reuters, the Singapore police have virtually unregulated access to users’ geolocation data, although they claim they only use the data for criminal investigations.

Figure 3: YouTube screen of Desmond Tan said Singapore police can obtain TraceTogether Data

Since then, although the government has announced the new restriction legislation on the usage of contact tracking data that it can only be used in the investigation of terrorism, murder, kidnapping, and the most serious drug trafficking cases.

Figure 4: New legislation about TraceTogether data access for criminal investigation

This behavior still caused anger and critiques from the public. As the public is disappointed about the government’s breach of trust and worried about their data.

User’s Dilemma about Personal Data Protection

Industrial-scale processing of personal information is enabled by terms of service and privacy agreements (Flew, 2021). Although most personal data usage related information of the platform will be written in the platform’s terms of services which ask users to agree before they sign into the app and it will normally claim the protection of users’ privacy, it doesn’t mean it will protect users’ rights and benefits. The terms of services documents are like constitutional documents as they set the rules of how users can participate in the online platform, but most of the time, it does not set any limits or rules regarding how those in charge should behave (Suzor, 2019).

In this case, users have the right to refuse, but if they do not sign the terms of services, they cannot use the application and achieve the self-data-protection. If they do continue the usage the platform, it means they accept the rules set by the platform (Suzor, 2019). Under the influence of COVID-19, if they want to continue their normal offline daily life in Singapore, they need to use the application which means they must accept the terms of services anyway. The cooperation between SafeEntry and TraceTogether is part of the reason that most people in Singapore have to use TraceTogether without any other choices. As the public is required to use TraceTogether to scan the QR code and do the digital check-in within the public space which is certified by SafeEntry to walk into the public place. Therefore, users who care about their data protection and concerns about data misuse by government might be caught in a dilemma. The possibility to get the protection from government and platform is less as when the platforms are unable to present the clear and transparent usage of collected users’ data and constantly change the platform’s terms of service, it is difficult for users to protect their data privacy and avoid the data misuse issue.

Data Misuse Raises Fears of Surveillance

We can identify other intentions of the government regarding the collected data except for outbreak management. The government constantly claimed the purpose of data collection is only for outbreak management and introduce the used code of the application to reduce public concerns about state surveillance. However, they have not been able to provide any formal or legislative assurance to promise they will never misuse the collected data even if avenues for abuse exist (Lee & Lee, 2020). However, after they provide the database access to police for criminal investigation, they immediately released the new legislation to make this behavior legal. It is obvious to identify that the Singapore government’s intentions for these data have gone beyond the original intention.

It seems that the purpose of data collection is to better achieve Coronavirus prevention. However, it can be seen as constantly testing the bottom line of public privacy data collection and surveillance. After all, personal data can be seen as a valuable resource in the digital age and the analysis of the data will make the future behavior of people predictable (Flew, 2021). Public data collection can also achieve citizen behavior surveillance. As outbreak management is a government behavior, the specific way of outbreak management is also the choice of the government.

Moreover, the TraceTogether application is developed by a related government department which means the government took absolute management control of the platform. If the government misuses the collected data or collect the data for surveillance purpose, there is no third organization that can stand out to regulate. Therefore, the privacy concern of the public is a trust problem to some extent.

Trust crisis is a serious problem between the government and the public that not only occurs in Singapore. The larger societal context for concerns about the “black box “of data management is the crisis of trust in social institutions including the government (Flew, 2018). The Public’s Distrust of government institutions is also due to the previous data misuse or leakage of records from not only the Singapore government but also from other countries.

In 2019, public officers reported 108 cases of data leaks by the Singapore government. Moreover, the Coronavirus tracing data misuse issue also happened in German caused by German police as they also used the tracking data for criminal investigation. Based on the research from the Edelman Trust Barometer (Flew, 2018), they found the general level of trust towards government institutions has been declining throughout the 2010s. There are signs that Singaporeans are nervous about handing over data to the government (Han, 2021) and this concern led to the low downloads of the TraceTogether at the beginning of the program. One reason that led to the low trust in the government might be the law in Singapore doesn’t empower individual users and the government institutions in Singapore are exempt from the Personal Data Protection Act (PDPA) (Han, 2021). This law is only used to regulate the behavior of data collection and usage in private sectors. It means that the behavior of data collection from government institutions lacks regulation from Institutions with a deterrent effect.

Data Access Regulation in the Post-COVID Age

The data misuse behavior of the Singapore government represents the limitation of data regulation to some extent. The regulation question of data misuse is complex and a struggle for all stakeholders. As Flew (2021) argued that data regulation is hard to resolve under the current legal and regulatory framework, especially current legislation majorly cares about users’ privacy rights instead of personal data. Although the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) set the regulation content for data protection and provide the legal frame for data misuse and private data protection, it still provides clear exceptions for enforcement and consent-based situation (Navarre, 2022) which can become confusing due to unclear platform permission.

Figure 7: Few key points about GDPR

However, under the influence of COVID-19 pandemics, many countries adopted digital approaches and contact tracing applications to conduct outbreak management which made data regulation and protection became imperative. Rather than a single organization taking the regulation responsibility, co-regulation between different stakeholders might be more suitable. In fact, co-regulation has been a feature of regulatory theory as it asks the regulators can set the general rules and laws which can not only rule the platforms but also regulate government (Flew, 2018). In this case, co-regulation seems like an imperative approach which is perhaps one of few ways to restore the public trust in the government’s data collection program.

Although finding an authoritative third-party which suitable for data management is difficult to be achieved in a short time, it doesn’t mean that the government which adopt the contact tracing application as the major approach to manage the outbreak do not need to adopt the data-related practice adjustment. The government might need to clearly define the data access right and purpose to users and set the new legislation to regulate it. Moreover, regularly and clearly displaying the usage of collected data can also help to re-build the trust between public and the government.

Conclusion

This blog has discussed the TraceTogether application and Singapore government personal data misuse issue majorly focused on three aspects. Firstly, we talked about whether the platform’s terms of service protect users’ data and the current dilemma of Singapore users regarding the usage of TraceTogether. Then, we discovered how data misuse led to the public trust crisis towards the Singapore government to link the data collection with digital surveillance. Finally, we discussed the thinking about future data regulation in the post-COVID age.

In conclusion, the data misuse issue might keep coming to public attention under the general environment of COVID-19. Once such situations happen more frequently without any authoritative and emerging third-party stakeholders to regulate, the government might need to face the situation of gradually losing public trust. The public will remain in a mood of insecurity, constantly concerned about the safety of their personal data and whether they will be surveillance by the government.

Reference List:

- Flew, T. (2021). Regulating platforms (pp. 72–79). Cambridge: Polity.

- Flew, Terry (2019) ‘Platforms on Trial’, Intermedia 46(2), pp. 18-23.

- Han, Kirsten. (2021a, January 5). Surveillance in the name of Covid-19. Retrieved April 6, 2022, from Rest of World website: https://restofworld.org/2021/trace-together-forever/

- Lee, T., & Lee, H. (2020). Tracing surveillance and auto-regulation in Singapore: ‘smart’ responses to COVID-19. Media International Australia, 177(1), 47–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/1329878×20949545

- Li, V., Ma, L., & Wu, X. (2022). COVID-19, policy change, and post-pandemic data governance: A case analysis of contact tracing applications in East Asia. Policy and Society, 41(1), 01–14. https://doi.org/10.1093/polsoc/puab019

- Navarre, B. (2022, January 19). COVID-19 data-driven spark privacy and abuse fears. U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved from https://www.usnews.com/news/best-countries/articles/2022-01-19/contact-tracing-biometrics-raise-privacy-concerns-amid-pandemic

- Suzor, Nicolas P. 2019. ‘Who Makes the Rules?’. In Lawless: the secret rules that govern our lives. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 10-24.

- Yaraghi, N., & Lai, S. (2022, January 13). How the pandemic has exacerbated online privacy threats. Brookings. Retrieved from https://www.brookings.edu/blog/techtank/2022/01/13/how-the-pandemic-has-exacerbated-online-privacy-threats/