Filter bubbles and opinion polarization

case study with TikTok

In the context of information overload, it is difficult for users to find high-quality content efficiently without algorithmic recommendation. However, when they rely too much on algorithms, they could fall into filter bubbles.

Filter Bubbles

Have you ever been hooked for hours on a mobile app when you’re trying to unlock your phone to find something you need? You may think your mobile devices knows you very well. But please be warned that you might already be trapped in a filter bubble.

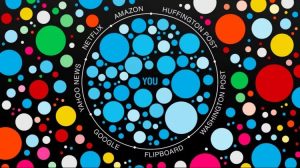

The “filter bubble” was first proposed by Eli Pariser, an American Internet activist, in 2011. Filter refers to the process of limited information available to individuals (Geschke et al., 2019). Pariser observed that his Facebook page was different from his friends then he proposed that: Facebook largely hides content almost completely different from the views of users, who live in the personal and unique information world constructed by Facebook algorithm (Pariser, 2011).

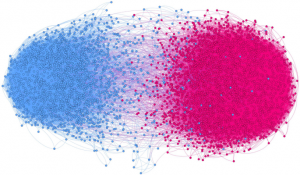

There are different opinions about the impacts of filter bubbles. Some optimists believe that there is no need to worry excessively about filter bubbles. Geschke, Lorenz & Holtz (2019) proved that personal echo chambers can still occur without social or technological filters by assuming the triple-filter bubble. Because people’s cultural experience is always selective and incomplete (Andrejevic, 2019). The Internet and social media platforms will eventually expand users’ access to impartial information (Haim et al., 2018). However, pessimists warn that the filter bubbles could minimizes information that contradicts individual attitudes (Geschke et al., 2019). For example, a personalized news site could more prominently display content from conservative or liberal media outlets based on users supposed political interests. As a result, users may encounter a limited range of political views. Another concern is that users often enter the filter bubble passively rather than actively selecting it (Pariser, 2011). Algorithm-based recommendation systems are responsible for shaping user cognitive boundaries. In this context, Just & Latzer (2017) believes that it is gradually influencing the way of thinking and behavior of human beings. It may promote group polarization while reducing social cohesion.

There is no doubt that the digitalization of Internet technology and cultural content has broadened the channels for people to obtain and receive information. However, it may change as more and more firms make personalized recommendations standard for various applications (Tao et al. 2020). Just & Latzer (2017) argue that “Personalization”, as a basic feature for algorithms to help users construct reality, is based on users’ online portraits, behaviors and interests. It seems that those who spend more time online are more likely to be exposed to a variety of news and information. However, Andrejevic (2019) warns us that exposure to opposing views and evidence rarely causes people to deliberate rather than further solidify their positions. When those applications try to tailor services to our personal preferences, there is a danger that we may be trapped in filter bubbles, unable to access information that challenges or broadens our cognitive. In these information cocoons, all interesting content becomes addictive and cannot be stopped (Pariser, 2011). Since the content users see basically meets their interests, which is likely to lead to users watching them frequency for hours or even addiction (Zhao, 2021). In the context of information overload, it is difficult for users to find high-quality content efficiently without algorithmic recommendation. However, when users rely too much on recommendation algorithms, they can easily fall into filter bubbles.

#For You feed on Tiktok

“Algorithms” refer to rules and processes established for machine-driven activities such as computation, data processing and automated decision making (Mansell and Steinmueller, 2020). The nature of an algorithm is that it can be improved over time through repeated interactions with users (Flew, 2021). Short video app TikTok’s elusive algorithm has long been a topic of fascination because it does well in giving users the content they crave (Sarah Fisher, 2021). Turn on TikTok and you’ll see a stream of popular videos tailored for your interests. But when your friends launch TikTok on their phones, they may see something different. TikTok calls this mainstream content the “For You” feed because it’s customized for individuals.

TikTok vice President Michael Beckerman has publiced to the press about the algorithmic logic behind “For You Page”. He said that every app faces a cold start problem when it’s first released, Tiktok is no exception. At the very beginning, Tiktok didn’t have any data to learn what users were interested in. When a new user enters the app, it asks him/her to select a category they are interested in, such as pets or travel, in this way, it helps system to customize the initial recommendation. If users skip category selection, TikTok will show a general feed of popular videos until there is more input. Once TikTok gets its first set of likes, comments and reruns, it will start making early recommendations. As users continue to use TikTok, the system takes into account their changing tastes, it would consider the videos you like or share, the accounts you follow, the comments you make, and the content you create to help identify interests, all of which will further customize your TikTok experience. To a lesser extent, it also uses your device and account settings, such as language preferences, user location settings, and device type. But Michael clarified these factors weigh less in a recommendation system than others because they are more focused on ensuring that the system’s performance is optimized.

TikTok vice President Michael Beckerman has publiced to the press about the algorithmic logic behind “For You Page”. He said that every app faces a cold start problem when it’s first released, Tiktok is no exception. At the very beginning, Tiktok didn’t have any data to learn what users were interested in. When a new user enters the app, it asks him/her to select a category they are interested in, such as pets or travel, in this way, it helps system to customize the initial recommendation. If users skip category selection, TikTok will show a general feed of popular videos until there is more input. Once TikTok gets its first set of likes, comments and reruns, it will start making early recommendations. As users continue to use TikTok, the system takes into account their changing tastes, it would consider the videos you like or share, the accounts you follow, the comments you make, and the content you create to help identify interests, all of which will further customize your TikTok experience. To a lesser extent, it also uses your device and account settings, such as language preferences, user location settings, and device type. But Michael clarified these factors weigh less in a recommendation system than others because they are more focused on ensuring that the system’s performance is optimized.

The Tiktok “For You” page customizes a fully personalized video stream that matches the user’s personality, content markup, and environment characteristics. As mentioned earlier, users always passively receive TikTok’s personalized recommendations, when a video is over, users simply swipe up to start watching the next one. It actually costs very little and is simple to operate. This is considered a huge revolution for users’ habit of obtaining information on the Internet (Zhao, 2021). It greatly eases people’s efforts to get the information they want and saves them from being overwhelmed by information. The algorithm is seen as a vital factor in TikTok’s success.

At the individual level, personalized content may secure and reinforce an individual’s existing attitudes, behaviors and identities. It increases individual certainty and security (Geschke et al., 2019). But at the same time, TikTok’s ability to insulate users from the rest of the information on the site and immerse them in their preferred world of information could increasingly limit their views on particular topics, hampering their growth. From the social level, The Conversation (2020) reports that the influence of social media on political activities is usually reflected in two aspects: First, social media provides a place for influencers; Second, people usually interact with like-minded people, also called homogeneity. Geschke et al. (2019) argue that in the political realm, Internet users prefer to consume information that confirms their ideology. In this way, recommendation algorithm has also led to an online filtering bubble, in which echo chambers amplify information that people tend to agree with and filter out information that disagrees with their views, then it gradually polarizing the public ideologically.

Bigtent Creative and political filter bubble

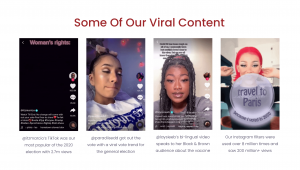

Bigtent Creative is a grassroots digital organization that harnesses the power and energy of Gen Z’s collective voice. During the 2020 U.S. election, it enlisted talent from music promoters, influencers and more to sponsor short video content on TikTok to persuade users to sign up as voters.

For example, they mixed rapper Cardi B’s song WAP with a message calling for votes, then released it via Tiktok. Cardi B has 17.2 million followers on TikTok. Based on the TikTok’s algorithmic logic, once this video is circulated on TikTok, Cardi B’s followers will certainly see it first. Then videos with the same political interest appear more and more on the phone screens of people who watch them.

In addition, Bigtent Creative cooperated with popular TikTok accounts to advertise to unaffiliated voters, where they can register to vote. But the so-called “vote chain” contained anti-Trump messages, such as: “Trump is trying to ban TikTok again… Can we kick him out of the White House?” (BBC). All of this runs the risk of polarizing communities to a large extent even though the content no longer be able to access on Tiktok.

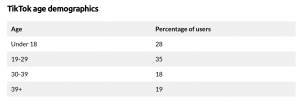

It’s worth noting that TikTok’s user base is much younger than that of other social media platforms (Smith, 2020). US young people (ages 19-29) accounted for 35% of TikTok’s active users as of 2022. This is followed by users aged 10-19. They account for 28% of users. Young people are still figuring out their political beliefs, which is likely to be heavily influenced by content created on TikTok because most of them were created by their peers rather than politicians or their parents. Young people may not know that political bias and filter bubbles exist. So, before TikTok comes up with countermeasures to address the political filter bubble, we all have to recognize them in TikTok’s use and understand how they got there (Smith, 2020).

Although TikTok states it actually recognizes that catering too much to users’ personal tastes can lead to a limited experience, tiktok is adjusting its algorithms to keep users as fresh and diverse as possible for your pages. For example, it adds videos to the For You feed that seem unrelated to the interest you’re expressing. It’s part of the company’s attempt to increase diversity by giving users the chance to stumble upon new content categories and new creators, and letting them “experience new perspectives and ideas.” Tiktok said “Our goal is to find a balance between content and advice that’s relevant to you, and help you find content and creators that encourage you to explore experiences you might not otherwise see.” (Sarah Perez,2020). The question we need to consider, however, is: to what extent is the platform’s claim credible?

Conclusion

In the digital era, people are used to share their experiences digitally, and the firms/platforms will further professionalize recommendation systems to maximize the time users spend on their sites. At the individual level, personalized recommendation may secure and reinforce one’s existing attitudes, behaviors and identities. However, at the social level, it tends to increase opinion polarization among various groups, cut off their communication links, as well as lead to attitudinal clustering and social polarization. In the age of information explosion, it is difficult for users to find high-quality content efficiently without algorithmic recommendation, but users are easily exposed to the risk of filter bubbles and opinion polarization if they rely too much on algorithm. The good news is that it is not too late to recognize this problem, and not blindly following the algorithm is the first step out of the filter bubble (Noble, 2018). Users need to realize that news consumption should be an active, ideologically diverse process. In order to avoid group polarization, users need to consciously look for different sources when acquiring information. Without comprehensive insights, it is impossible to make informed decisions in policies and public discourse (Borgesius et al., 2016). Finally, the filter bubble needs to be effectively solved from different perspectives, including but not limited to individual, social as well as technical perspectives (Seaghdha et al., 2012). As ordinary users, it seems difficult for us to influence or change the framework at the social and technological level, but we can choose to remain skeptical and critical about it. As Michael Beckerman said, “…now our society is in an era of technology shock, where people are skeptical about platforms, how they adjust content, how their algorithms work…”

Reference

Andrejevic, M. (2019). ‘Automated Culture’, in Automated Media. Milton: Routledge.pp. 44-72.

Flew, T. (2021). Regulating platforms. Cambridge, UK: Polity. pp. 79-86.

Just, N., & Latzer, M. (2017). Governance by algorithms: reality construction by algorithmic selection on the Internet. Media, Culture & Society, 39(2), 238–258. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443716643157

Geschke, D., Lorenz, J., & Holtz, P. (2019). The triple‐filter bubble: Using agent‐based modelling to test a meta‐theoretical framework for the emergence of filter bubbles and echo chambers. British Journal of Social Psychology, 58(1), 129–149. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12286

Mansell, R., and Steinmueller, W. E. (2020). Advanced Introduction to Platform Economics. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Noble, S. U. (2018). Algorithms of oppression : how search engines reinforce racism. New York, NY: New York University Press. pp. 15-63. https://doi.org/10.18574/9781479833641

Pariser, E. (2011), Beware online “filter bubbles”, „TED”, [online: 10 September 2019],

https://www.ted.com/talks/eli_pariser_beware_online_filter_bubbles

Sarah Perez. (2020). TikTok explains how the recommendation system behind its “For You” feed works – TechCrunch. TechCrunch.

Smith, R. (2020). TikTok: Filter Bubbles and the “Algorithm”. https://sites.psu.edu/rsmith272blog/2020/09/18/tiktok-filter-bubbles-and-the-algorithm/

The Conversation. (2020). How TikTok teens amplified political activism and threatened Trump’s political campaign. In TheNextWeb.com [BLOG]. Amsterdam: Newstex.

Zhao, Z. (2021). Analysis on the douyin (Tiktok) Mania Phenomenon Based on Recommendation Algorithms. E3S Web of Conferences, 235, 3029–. Les Ulis: EDP Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202123503029