Introduction

The popularity of the Internet has brought about tremendous changes in the way of life of human society. Digital media has accelerated the speed of coverage with the advancement of human technology. Contemporary people are using digital media network devices and platforms, thus creating an era of big data. More, through big data, Internet automation algorithms are also recognized by many people. Media consumption is increasingly influenced by automatic algorithm selection. For example, automatic algorithm selection has led to the growth of algorithm personalization. Filter bubbles are the result of certain forms of algorithmic personalization. However, it can result in people only accessing information that confirms their opinion or communicates with like-minded people. The polarization of opinion for and against has negative democratic effects on society (Just & Latzer, 2016). The negative effects are mainly due to the self-closure and independence of opinion caused by filter bubbles. Democracy requires citizens to see things from each other’s perspectives, but filter bubbles keep us more and more enclosed in our bubbles. Democracy needs to rely on common facts, but filter bubbles have provided us with parallel but independent universes (Pariser, 2011).

This blog will address the negative democratic impact on human society of prejudice caused by filter bubbles and polarization of opinion, self-enclosure, and independence of opinion. A very shocking thing happened in 2017, and that was Brexit. In fact, the key factor that shocked so many about Brexit was the filter bubbles in social media. This blog will provide an analysis of the split of opinion on social media in the context of Brexit, in conjunction with Pariser and Just exposition of filter bubbles. Moreover, I’ll wrap up Brexit, discussing ways to avoid division of opinion.

Algorithmic Bias

The bias of the algorithm comes from the predictive nature of the data. Through big data, people’s social behaviours are transformed into network behaviours. Users’ network behaviour forms quantitative data, allowing real-time tracking and predictive analysis (Dijck, 2014). Algorithms will process this data and predict what content the user like and push it to the user. According to Eli Pariser (2011), these algorithms create a unique world of information for each of us, which fundamentally changes the way we encounter ideas and information. Algorithms keep us from reaching groups that disagree with our opinions, which results in our standpoint not being dissented. When the standpoints we hold are in a no argue environment, we blend into that environment. It has led to our biased opinions and ultimately polarized opinions. Filter bubbles undermine our right to discourse and mutual understanding, inconsistent with the ideals of democracy.

Self-Enclosure

Filter bubbles can skew the information users receive, and at the same time, they can create a self-enclosed environment for users. In fact, politicians, journalists, activists and other social groups are often accused of living in filter bubbles (Bruns, 2019). They are immersed in this harmonious community exchange and cannot extricate themselves. Multiple self-enclosed social circles will emerge as more and more users are attracted to communities with the same opinion. In 2017, Obama mentioned in his farewell speech that many felt it was safer to retreat into their bubble, rather than engage in discussions with different proposals. This sense of security makes users like to stay in self-enclosed social circles, which causes most users to lose the right to receive new messages.

Independence

creating “compulsive media” to get users to click on more content. Personalization algorithms used by mainstream platforms such as Facebook and Google display similar views and ideas on behalf of users without their consent and remove opposing views. Users may get different search results for the same keyword (Pairser, 2011). When in an environment of compulsive media, users can only browse more self-identified content. Therefore, the user is affected by the filter bubble, which will form a parallel and independent world. It affects the freedom of consciousness of the individual and goes against the democratic ideals of self-determination, awareness, being able to make choices and respecting the individual (Bozdag & Hoven, 2015).

What is Brexit?

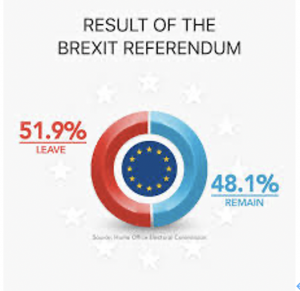

Brexit is a combination of the words “British” and “exit”, used to refer to the United Kingdom on June 23, 2016, when the United Kingdom voted to leave the European Union. In the June 2016 referendum, “Leave” won 51.9% of the votes, or 17.4 million votes; “Remain” won 48.1%, or 16.1 million. The result of such a vote was very unexpected.

Brexit referendum result (IG, n.d.)

From an economic standpoint, every time the likelihood of a “Brexit” vote to leave the EU rises, the value of the pound falls. A cheaper pound means lower prices for UK goods and services (Solman, 2016). Therefore, after the Brexit result came out, the pound fell to its lowest level in 30 years. Former British Prime Minister David Cameron announced his resignation the next day after calling for a referendum and backing Britain to remain in the European Union (EU) (Hayes, 2021). The impact of Facebook and Twitter on Brexit is significant. The ‘Brexit’ movement has more followers and engagement on these social media platforms and has also been more successful in spreading pro-Brexit hashtags and messages (Difranzo & Garcia, 2017).

Filter Bubbles and Brexit

Why are most people surprised by the outcome of Brexit, or by the number of supporters “Brexit” has? Filter bubbles hinder the right to know and speak to many voters. Just (2016) said: “The fact that algorithms choose to assume (minor) agenda-setting and (minor) gatekeeping roles through news aggregators, ranking algorithms in discussion forums, and social online networks such as Facebook leads to the fact that evaluation algorithms have a large influence on the way public opinion is formed.” Many “Remainers” on social platforms searched with the hashtag “Remain”. Through algorithms, they naturally form a social circle. It’s a closed circle, and they can’t receive news content from the “Leave” tab. According to group psychology, people want to be around those who are just like us and reinforce our worldview. People form tribes (subreddits, Tumblr fan groups, Facebook groups, Google+) based on interests, location, employment, affiliation, and other details. These tribes have their own rules that cause beliefs to strengthen. Anyone who disagrees could be kicked out of the community. Sociologists call this behaviour “community reinforcement” (Fs, n.d.). This is not a democratic act. Democracy is where citizens address social problems and public concerns by reasoning together about how best to address them (Bozdag & Hoven, 2015). “Remainers” have no opposition in closed social circles, and their opinions are not divided. Therefore, when the Brexit result came out, these “Remainers” couldn’t believe it was true.

Brexit: Fraying union (Milne &Spiegl, 2016)

Algorithms facilitate individualization in society. Algorithms lead to fewer unplanned encounters and fewer shared experiences, as well as a decline in social cohesion. It results in less privacy and freedom for users (Just & Latzer, 2016). On social media platforms, people who support “Remain” are confronted with content that shares the same views. This reduces their desire to share their experiences. When people are in a comfortable environment, they quickly adapt to the environment and “fall asleep” quickly. Therefore, many “Remainers” just silently receive the content recommended by the automatic algorithm and do not take any actions to share. Such behaviour has exacerbated the individualisation of voters in the Brexit referendum. Eli Pariser (2011) said: “Personalization filters serve an invisible self-promotion, instilling in us our ideas, amplifying our desire for the familiar, and making us forget the dangers lurking in the dark and unknown.” Voters via Algorithms are “brainwashed” with full confidence that the opinions they support will succeed. They forget that there is a negative opinion.

Moreover, in the Brexit referendum event, many voters also appeared cognitive bias. Biased media sources such as newspapers, political polls, and television influence voters. A study found that Fox News coverage had the power to change 10,757 votes in Florida during the 2000 U.S. presidential election. That’s enough to topple the Republican presidential nominee (Pariser, 2011). Facebook and Twitter were the most influential social media platforms in the Brexit referendum.

Algorithms Today (Abdallah, 2018)

Many voters were guided to vote by public opinion on the platform. Opinion holders play more of a facilitator role on these social platforms. Because people with opinions are not influenced by algorithms, they are more convinced of their opinions. However, people who are neutral or uninformed about Brexit are affected by more filter bubbles. The biggest investment in social media will be to attract those who hadn’t considered a referendum, which could prompt those who hadn’t to vote (Hodson, 2016). In the Brexit referendum, the majority of those who supported “Brexit” were older people who were not regularly active on the Internet (Fs, n.d.). Their awareness can be misled by biased media, which leads to their search engine performance being determined by those biases from the start. As a result, algorithms cannot recommend content exactly as people originally intended, and the prejudice in the filter bubble has hidden negative effects on a democratic society.

However, the disruption of the filter bubble in the Brexit referendum is avoidable. From a public policy perspective, the personalization bias of algorithms construction affects democracy. This requires the full democratic legitimacy of this form of governance through algorithms to enable coevolutionary interactions with algorithmic governance (Just & Latzer, 2016). The main task of algorithm governance is to improve the design of algorithms. Algorithmic design can demonstrate how design creates and removes filter bubbles that shape democratically sensitive issues that shape public opinion (Just & Latzer, 2016). But the governance of the algorithm needs more time to improve and optimize. Before the algorithm is optimized, people can avoid being affected by filter bubbles through their browsing habits. Firstly, the voting UK should browse on platforms that offer a wide range of views, such as national news platforms such as the BBC. Secondly, voters can use traceless browsing when browsing news about Brexit events, which can avoid algorithmic domestication of you. The last but not least, we can browse some nutritious content, that is, switch from entertaining news to educational news. Voters can browse the views of some experts instead of discussing and browsing in the non-professional community.

Conclusion

Overall, the effects of filter bubbles are profound. Self-closure, independence, and prejudice are all characteristics of the polarization of opinion created by filter bubbles. Algorithmic optimal governance is a must, especially in democratic countries. Filter bubbles undermine the purpose of democracy and impede the liberty and equal rights of citizens. Many other Brexit-like cases reveal the impact of filter bubbles on public policy. We should learn to recognize the diversity of things on the Internet and avoid being influenced by the personalization of algorithms. Although algorithms and we are mutually successful, we should help society form cohesion and jointly contribute to the governance of algorithms.

Reference list

- Abdallah, A. (2018). [Photograph of Algorithms Today].

https://medium.com/jsc-419-class-blog/algorithms-today-cf5f1e9d643b

2. Bozdag, E., & Van Den Hoven, J. (2015). Breaking the filter bubble: democracy and

design. Ethics and information technology, 17(4), 249-265.

3. Bruns, A. (2019). Filter bubble. Internet Policy Review, 8(4).

https://doi.org/10.14763/2019.4.1426

4. DiFranzo, D., & Gloria-Garcia, K. (2017). Filter bubbles and fake news. XRDS:

crossroads, the ACM magazine for students, 23(3), 32-35.

5. Dijck, J.V. (2014). Datafication, dataism and dataveillance: Big Data between

scientific paradigm and ideology. surveillance and society, 12, 197-208.

6. Fs. (n.d.) How Filter Bubbles Distort Reality: Everything You Need to Know.

How Filter Bubbles Distort Reality: Everything You Need to Know

7. Hayes, A. (2021, May 22). Brexit. Investopedia. https://www.investopedia.com/terms/b/brexit.asp

8. Hodson, H. (2016, June 1). How your Facebook feed will affect your Brexit vote. [Media Release]. https://www.newscientist.com/article/2091552-how-your-facebook-feed-will-affect-your-brexit-vote/

9. IG. (n.d.). [Photograph of Brexit referendum result]. https://www.ig.com/en/financial-events/what-is-brexit

10. Just, & Latzer, M. (2017). Governance by algorithms: reality construction by algorithmic selection on the Internet. Media, Culture & Society, 39(2), 238–258. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443716643157

11. Milne, R. & Spiegel, P. (2016). [Photograph of Brexit: Fraying union].

https://www.ft.com/content/8710df70-d49d-11e5-8887-98e7feb46f27

12. Pariser, E. (2011). The filter bubble: How the new personalized web is changing what we read and how we think. Penguin.

13. Solman, P. (2016, June 24). Brexit: 4 reasons it comes as a shock. PBS. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/economy/brexit-four-reasons-it-comes-as-a-shock