Who can protect patients’ privacy on the platforms during the pandemic?

The leak of online privacy

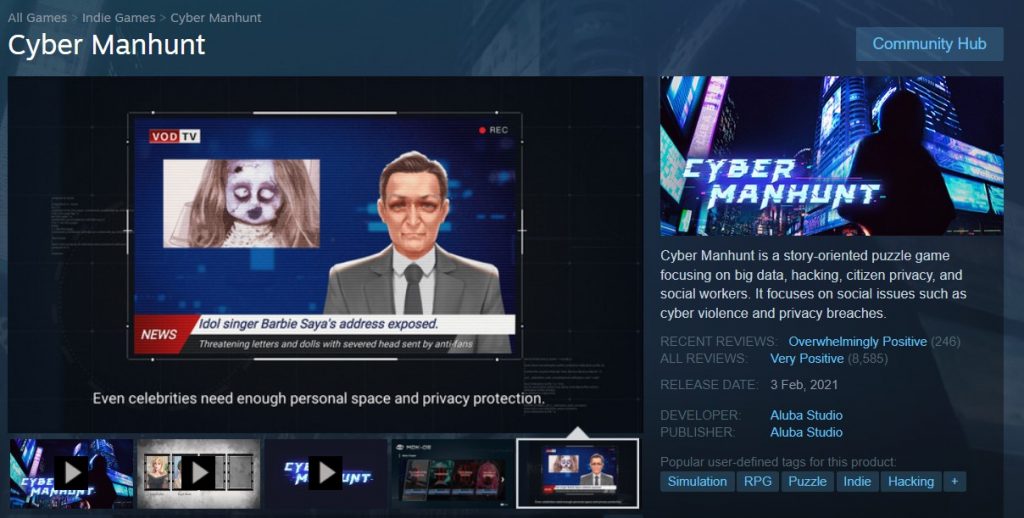

When I played Cyber Manhunt, I was alarmed by the threats to privacy on the Internet. Cyber Manhunt is a game released by Aluba Studio in August 2020. In this game, players can take on the role of hackers and steal information from their targets through the databases of Titan (an Internet company) and even the most common search engine. The privacy of all targets is exposed on the Internet and players can capture door numbers from the background of celebrity selfies or discover tracks from students’ social media. In addition, Titan can provide an excellent database containing information about almost all citizens. As soon as users have leaked enough information online, their real identities, which hide behind the account of platforms, can be found by hackers through this database.

Source: https://store.steampowered.com/app/1216710/_/?l=schinese&curator_clanid=26214428

Of course, it is just a thrilling video game. Few platforms will collect your information to find out who you are. Although these platforms understand that some information is private and protected by law, they still want to get the information of users. According to Van Dijck et al. (2018), datafication is one of the critical processes of platforms’ work because platforms themselves are fueled by data. Some platforms are collecting and using large amounts of information about their users without permission. Nearly all forms of user interaction could be captured and used as data (Van Dijck et al., 2018). Goggin et al. (2017) state that this highly granular data reveals users’ interests, beliefs, political orientation, individual families, social networks, and other information. Some digital platforms think they can use this data to improve users’ online experience and provide more personalized services.

However, not everyone can enjoy this intelligent service in peace as they see their pay price – their privacy is compromised. Privacy is protected by law as a fundamental human right, although not every country focuses on online privacy. There is an example of Australia. As a fundamental interest that the law should protect in Australia (ALRC, as cited in Goggin et al., 2017), privacy is considered an offline right and viewed as a separate online right (Marwick & Boyd, 2019). The protection of online privacy is one of the challenges of all platforms.

A case of covid-19 patients

There is a case about the online privacy leak of COVID-19 patients. During this particular period, COVID-19 and Omicron seriously affected the life and work of the citizens. In many countries, there is an established public health practice called contact tracing. This kind of tracing involves “interviewing someone who tested positive for infectious disease in order to identify and notify others who may have come into contact with that person” (Mullin, 2022). In China, the authority used contact tracing to quickly determine the 14-days routes of confirmed patients and post this information on social media. In addition to publishing the routes of these patients, this flow report may also indicate their gender, age, occupation, and even place of work. In other words, such information may involve the privacy of these diagnosed patients.

Source: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/php/contact-tracing/index.html

Lisa M. Lee, an epidemiologist and bioethicist at Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, states that the information that public health officials collect should be only used for public health purposes and cannot be shared with law enforcement and so on (Mullin, 2022). I will not discuss whether this act in China harms the privacy of a few people for the benefit of more citizens in this blog. I will analyze the governance of platforms under these situations. As Parker et al. (2016) point out that governance of platforms is a series of rules that mainly discuss who can become participators, how to address online conflicts, and other questions. As users of some platforms, it is necessary to know how to protect privacy by learning and even joining the governance. Apart from it, it is valuable to discuss how platforms themselves and third-party organizations should effectively manage the platforms to respond quickly to such privacy breaches.

On December 8, 2020, Ms. Zhao of Chengdu, China, was diagnosed with COVID-19. Her track was posted on social media. She visited multiple entertainment venues during these fourteen days, including various bars. Some users continued to question her itinerary and even speculated and ridiculed her occupation on social platforms. Then, her information, such as name, age, ID card, phone number and some selfies, was exposed on the Internet. On December 9, Ms. Zhao released a statement explaining that she had endured harassment after being leaked privacy. That afternoon, the man who spread Ms. Zhao’s privacy was found and punished by the law. If you want to know more detail about this thing, you can see this link from BBC.

Something more terrible than the virus in this lady’s experience can be found. In the chaos of the Internet, dirty humanity can be seen. Although the platform has done its best to find the source of the privacy leak quickly, this inhumane privacy party has already caused a lot of traumas to Ms. Zhao. What’s worse, this thing changes the opinion of some citizens. In their opinions, the government and some platforms lack consensus on privacy protection in contact tracing. This situation may lead some citizens could deliberately hide their itineraries. According to Fahey and Hino (2020), the reason is that they fear revealing the privacy of their lives.

The more information you share, the more privacy is leaked.

In this blog, the critical process that the privacy of Ms. Zhao was leaked is related to her share on the Internet. Users can enjoy the benefit of platforms, such as simplifying accessing and using the open web (Gillespie, 2017). Some users like to share the highlights of their lives, which may reveal information about them. Some users post a photo or send a message on Instagram that doesn’t seem to show anything specific about them. Unfortunately, their privacy is compromised long before they know this critical fact.

Source: https://www.dailytut.com/windows/stop-website-tracking.html

Like them, Ms. Zhao is actively sharing her life on the Internet, and the incident itself is not wrong. It’s just that some users have used the information to compromise Ms. Zhao’s privacy and join in cyberbullying. In reality, some people who know her make sure this patient is Ms. Zhao through over-detailed information in the report. And then, some of them posted her more privacy on the Internet and spread the content she shared on social media. These contents were used to attack the character and work of Ms. Zhao, which caused more harm for her. Thus, to protect privacy, users of platforms could be vigilant and remember to hide specific information about themselves, such as cell phone numbers, home addresses, and other information, when sharing their lives. This information is relatively essential privacy and can be used by other users to threaten themselves.

How does the platform use user information?

As the public square where privacy breaches spread, platforms should take responsibility for patient privacy breaches and dissemination. There are many things that platforms can do. One of them is to require each user to register with a real name. In other words, the user would need to provide the platform with some information that identifies the user’s true identity before using the account. This is to quickly find users who spread privacy for legal recourse after a patient privacy breach. This means that there are countless situations in which individuals have to provide data initiative (Marwick & Boyd, 2019).

The most common way is the Terms of Service (TOS). The TOS can be considered the governing document of the Internet. Platforms and other companies can legally collect user information with the user’s permission. There are two very different views on observing users’ attitudes. The qualitative findings of Obar and Oeldorf-Hirsch (2018) suggest that some participants view the terms of service (TOS) policy as an impediment to the online purpose of users. Most participants want to enjoy their digital activities quickly, while a few are concerned about their privacy. However, Marwick and Boyd (2019) have different views about the attitude toward online privacy. They noted that users are deeply concerned about privacy and try to achieve it through innovative strategies. Most users have to compromise and agree to the TOS policy because they want to use the platform’s services successfully. These users can only hope these companies do not leak their data to more intermediates (Marwick & Boyd, 2019). As can be expected, such naive wishes usually fall flat.

Source: https://www.npr.org/2020/03/04/812264543/episode-976-terms-of-service

Suggestions and arguments on third parties

Third parties such as authorities are more credible than digital platforms driven by commercial interests. Some departments have to protect the privacy of Internet users. Karppinen (2017) states that policymakers and researchers should defend human rights and regard human rights as a central task of existing law. However, as Karppinen (2017) and Flew (2019) acknowledge, there are many digital rights and data protection debates. The front has less confidence to address this contention quickly, while the latter thinks the rules can be made around this area. Since authorities have the will to release this information in digital media, they should understand the destructive power of digital media and remain cautious. The most important premise is to protect the true identity of diagnosed patients and protect their privacy. Bored digital mobs should not be allowed to use the Internet and find out additional information about patients.

Source: http://bj.bendibao.com/news/2021124/287247.shtm

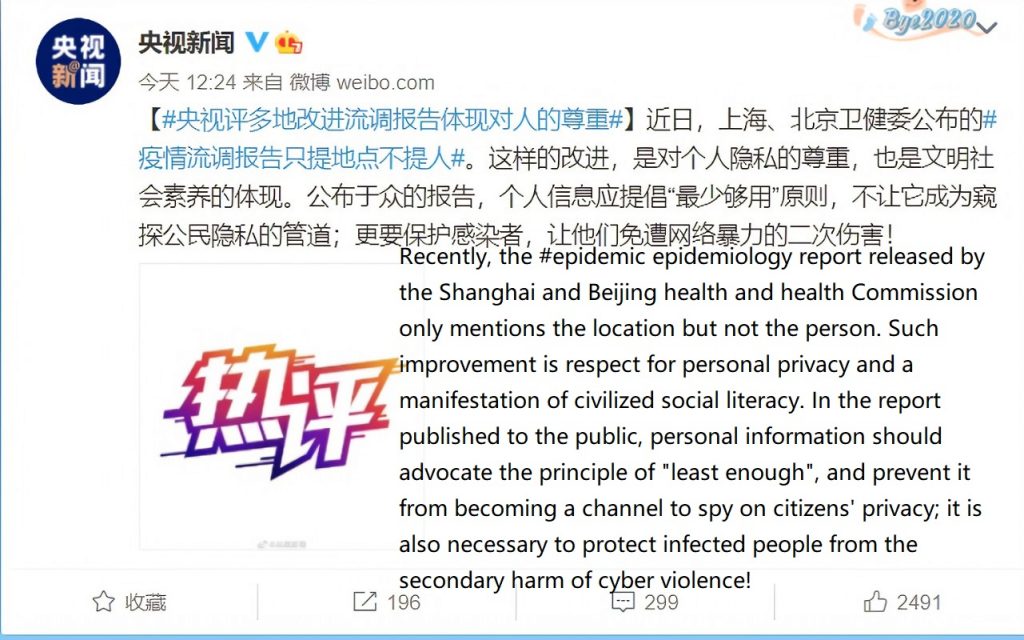

One suggestion is that the relevant government departments should confirm a standard. It may be necessary for the government to reveal limited information to alert other citizens, but, as it stands, the data revealed by local governments in each city is inconsistent. For example, the two cases announced in Macau on September 25, 2021, revealed the nationality and work of the patients, while the case information announced in Luoyang on April 3, 2022, showed only the recent whereabouts of the patients. Such an official report is likely to cause panic among Internet users. Some netizens believe it would increase the possibility of leaking the patient’s privacy and cause online and offline bullying.

Apart from confirming a standard, the government should also make severe selections about the platforms that publish information on epidemic prevention. It is necessary to prioritize the use of platforms with high national credibility and official accounts and regularly maintain the credibility of official statements on digital media. However, the authorities forgot one crucial thing: almost any user can take a screenshot of this report, change its information, and disseminate it on other platforms. Therefore, the government needs to monitor the spread of the flow investigation report on digital platforms, especially to limit the spread by unidentified accounts because they may reveal other information about the patient. Finally, the government should improve the laws and regulations related to the platforms. These current laws and regulations in China are not sound enough, which may cause the authorities difficulty holding platforms and users duly accountable. Media often ignore user privacy protection, partly because of the inadequacy of relevant laws and regulations as well as the insufficient punishment of the law.

Some scholars argue that the government is not entirely credible. According to Flew (2019), apart from the government, people need an independent third party to oversight social media and online content. The reason is that some regulatory governments lack credibility and even cause social and political unrest by cracking down on social media (Flew, 2019). However, it is nearly impossible to hope the government encourages the development of independent third parties due to conflict of interest. At the same time, these third parties may collaborate with digital platforms for financial rewards, which may compromise their users’ privacy again. Therefore, it is not easy to hope for an independent third-party organization to protect your privacy.

In Conclusion

In this particular epidemic period, everyone could become a confirmed patient and become a victim of privacy breaches on digital platforms. Thus, protecting patient privacy in times of epidemics requires the involvement and collaboration between the government and the platform. It is necessary for us to make relatively mature and all-around internet governance to protect confirmed patient privacy.

Reference

- Fahey, R. and Hino, A. (2020). COVID-19, digital privacy, and the social limits on data-focused public health responses. International Journal of Information Management, 55, p.102181.

- Flew, T. (2019) ‘Platforms on Trial’, Intermedia, 46(2), 18-23.

- Gillespie, Tarleton (2017) Governance by and through Platforms. In J. Burgess, A. Marwick & T. Poell (Eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Social Media (pp. 254-278). London: SAGE

- Goggin, G., Vromen, A., Weatherall, K., Martin, F., Webb, A., Sunman, L., Bailo, F. (2017) Executive Summary and Digital Rights: What are they and why do they matter now? In Digital Rights in Australia. Sydney: University of Sydney.

- Karppinen, K. (2017) Human rights and the digital. In H. Tumber & S. Waisbord (Eds.), Routledge Companion to Media and Human Rights (pp. 95-103). Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge

- Marwick, A. & Boyd, D. (2019) ‘Understanding Privacy at the Margins: Introduction’, International Journal of Communication, 12(2018), 1157-1165.

- Mullin, E. (2022). Calling Police Investigations ‘Contact Tracing’ Could Block Efforts to Stop Covid-19. Retrieved from https://onezero.medium.com/calling-police-investigations-contact-tracing-could-block-efforts-to-stop-covid-19-349cdc27766e

- Obar, J. and Oeldorf-Hirsch, A. (2018). The biggest lie on the Internet: Ignoring the privacy policies and terms of service policies of social networking services. Information, Communication & Society, 23(1), 128-147.

- Parker, G. Van Alstyne, M. & Sangeet, P. (2016). Disruption: How platforms conquer and transform traditional industries. In Norton & Co. (Eds.), Platform Revolution: How Networked Markets are Transforming the Economy (pp.60-78). New York: W. W.

- Van Dijck, J., Poell, T. & de Waal, M. (2018) The Platform Society, The Platform Society (pp. 5-32). Oxford: Oxford University Press