Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms and automation are transforming businesses, many jobs have been moved to automated systems, and AI’s contribution to productivity is boosting social and economic growth. The Internet has become an essential employment resource for job seekers. Various types of firms are gradually setting up online job boards, and there are also many intermediary websites open to these firms as recruitment platforms. Candidates can use these sites to get a large number of job referrals and to find the job they want.

Figure 1. Source: https://www.roberthalf.com/blog/job-market/10-best-job-search-websites

These platforms use algorithms that automate the processing of large-scale data to predict candidates for different positions. Gartner (2018) has predicted that by 2022, 85% of AI projects will have wrong decisions due to bias in data, algorithms or management and the teams that write them. Injudicious AI leads to potential biases in training data and algorithms that harm workforce diversity in the labour market (Parikh, 2021). Without improvements in algorithms and technology, prejudices and stereotypes in society will continue to deepen.

This blog will focus on the causes of algorithmic bias and uses the case study to discover the phenomenon of algorithmic bias in the recommendation system of Chinese job boards. Combined with the case, we will discuss how the algorithm bias arises from three aspects: the situation of data acquisition, the method of data interpretation and the embedded social and cultural background. Furthermore, targeted solutions will be proposed to address the current data bias and the lack of awareness of bias among professionals.

Algorithmic bias in job recommender systems of Chinese online job boards

Shuo Zhang, a PhD student in economics at the University of California, Santa Barbara, conducted a study on the recommendation systems of Chinese recruitment websites in 2021. She conducted this experiment on the four largest job boards in China and created 2,240 fictitious resumes, including male and female applicants of different ages. Based on the recommendations received from the system by gender, jobs recommended only for women pay less than men and require less experience and management skills, and the job descriptions for these positions may include words describing women’s personalities, reflecting stereotypes of women in the workplace (Zhang, 2021).

One feature of Chinese online job boards is that they allow employers to select the gender preferences of job seekers and do not reveal implicit conditions to them, so the algorithm in this does not operate based on a standard rule (Zhang, 2021). The information that directly links gender and job facilitates the employer to receive the corresponding gender candidates recommended by the system, and the biased data directly affects the algorithm results.

Besides the gender bias reflected in recommendation systems, gender-specific job ads pushed on these websites are very common. According to a study by Kuhn and Shen (2022) on gender discrimination in Chinese online job ads, depending on the age of the candidates, companies advertised more to men than women, while in the 25 to 35+ age group, the proportion of male ads increased three-fold, but, by contrast, the proportion of female ads decreased eight-fold, they argue that this restriction on advertising patterns is designed to keep women away from high-tech or more skill-demanding jobs. Regarding information acquisition, women are less recommended for jobs by the system than men, and the system has fewer opportunities to refer female candidates to employers.

Figure 2. A job Ad example of Baidu (Stauffer, 2018).

In theory, AI algorithms do provide efficiency, specificity and cost-effectiveness in the recruitment process that helps companies sift through large numbers of resumes; however, according to realistic feedback, AI algorithms rely on unconscious biased selection patterns, such as demographics and language, thus promoting bias in hiring (Parikh, 2021). It also explains that employers are taking advantage of the efficiency and convenience of algorithms to meet their discriminatory requirements on online job boards, so it seems that the recommendation systems are reinforcing the gender bias that already exists in the labour market.

How does algorithm bias happen?

Data bias

Machine learning is based on data sets, and data that do not reflect objective facts are inherently unrepresentative and can influence the fairness of algorithmic decisions. Flew (2021) said, data is the key for the algorithm to make decisions, and data often show bias in sampling practices, such as they favour groups that use mobile devices or higher income groups; in addition, these data reflect social bias, such as racial discrimination in the processing of crime data.

From the data collection perspective, data sets may be more skewed toward accessible groups, thus reflecting imbalances in terms of gender, race, and other dimensions, leading to a digital divide. According to GSMA Intelligence (2020), 234 million fewer women use The Internet than men; in middle – and low-income countries, women are 20% less apt to use smartphones than men. There is also a significant demographic gender imbalance in some countries, resulting in gender-biased user data generated by the Internet, and the data set is distorted by this inherent fact. Mikkelso (2021) also pointed to the general lack of adequate representation of girls and women in the training data set as the most pressing issue currently faced.

When the original data contains the existing social bias, the data based on human behaviour will affect the learning and operation results of the algorithm. The research of Mishra, Mishra and Rathee (2019) shows that algorithm design can learn gender bias, understand user gender, capture cultural bias and apply it in the network environment. When the algorithm’s training data is provided by biased human decision-makers, the same biased results will be generated (Rambachan and Roth, 2019).

Algorithm Bias

When we think about algorithm bias, we have to focus on a core issue that algorithms are written by humans, and the people who design them are establishing rules, so there is human bias behind the algorithm bias, although it may be unconscious.

“If there is sexism embedded within the data, they will pick up that pattern and exhibit the same sexist behaviour in their output. And unfortunately, the workforce in AI is male dominant.” Dr Muneera Bano said (Madgavkar, 2021). Approximately 73% of employees in the AI algorithms industry were unaware of malicious algorithms targeting women in the field, and 58% of employees were not aware that the algorithm is gender discriminatory (Hu, 2021).

However, reality reflects that algorithmic bias has become a potential problem with a widespread impact on society, hidden and constantly making unfair decisions in the dark. Developers usually do not disclose the exact data provided for the training of autonomous systems, so we can only see the final algorithm behaviour or learning model, and no user is even aware that data containing bias will be used (Danks & London, 2022). Pasquale (2015) believes that the privileges and values of the coding rules are formulated in the black box, the information imbalance between the user and the firm is severe, the decision-making process of enterprises and critical features are not known to users, and these defective models are hidden and cannot be corrected.

Besides, the algorithm learns from not only the data, but also from the interaction between the user and the platform and between the users is learned by the algorithm (Jiang et al., 2016). Similar to social media, in online job boards, recommendation systems recommend one-sided types of candidates to employers or human resources departments based on their browsing habits. If a recruiting agent keeps opening the resumes of male candidates, male candidates will be prioritized by the system, and if a recruiting agent receives a female candidate’s resume but never opens it, the job will not be recommended to women (Burke, Sonboli, & Ordonez-Gauger, 2018). The primary purpose of recommendation systems is designed to predict user interest, and thus fairness in recruitment is ignored when the system predicts and satisfies employer interests (Sonboli et al., 2021). However, it is a widespread phenomenon that the algorithm will learn the errors in the existing training data and a widespread to make decisions based on the existing stereotypes (Zhang, 2021).

Algorithms reflect the biases that exist in society, they almost imitate human behaviour and apply it to various decisions. Through these algorithmic results, we may find that AI is still subject to the current social order and is reinforcing the prejudices of human society. Noble (2018) argues that algorithms replicate the specific thinking as well as values of particular groups of people through deep machine learning, yet these people are controlling the most powerful institutions in society. AI systems are developed to serve existing dominant interests, which depend on social structures and broader politics, therefore, AI is equivalent to a registry of power (Crawford, 2021).

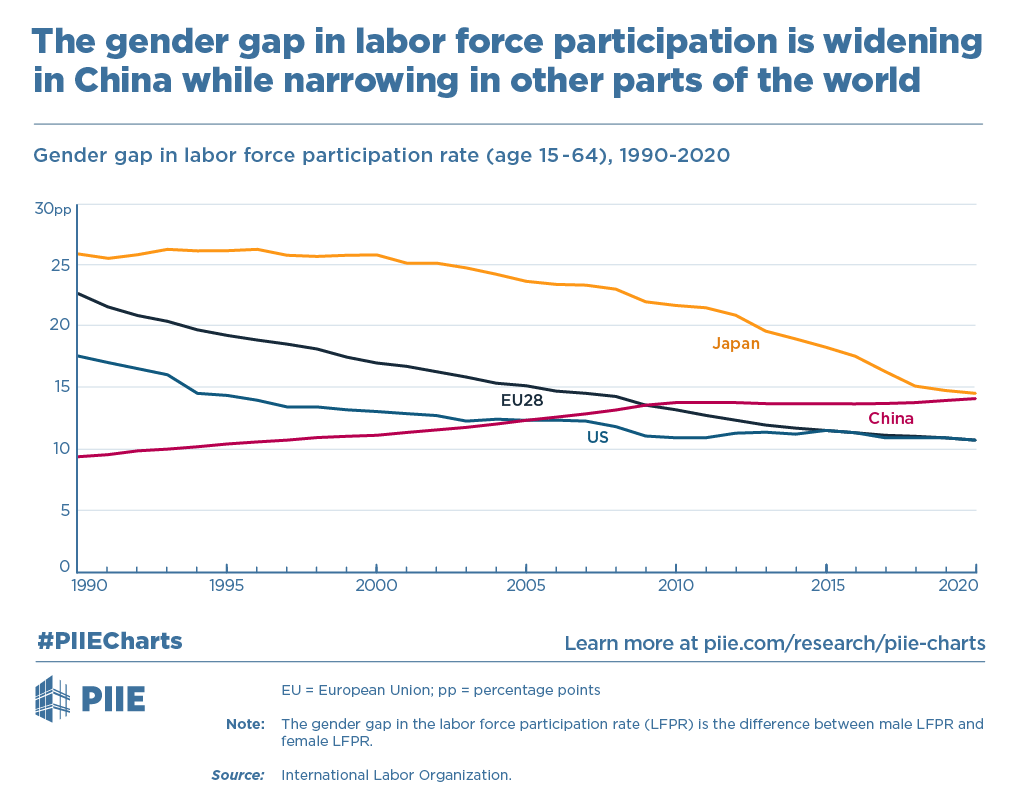

Figure 3. The gender gap in labor force participation is widening in China while narrowing in other parts of the world (Zhang & Huang, 2020).

The reinforcing effect of Chinese Confucianism on patriarchy has led to a long history of oppression of women’s status, resulting in gender discrimination in various areas of society. Employers on Chinese job boards can covertly manipulate gender preferences, recommending fewer jobs and lower wages to women than men, and companies setting gender pay differentials are realistic outcomes. According to research by Human Rights Watch (2018), nearly 19% of China’s national civil service positions explicitly give preference to male candidates or only male candidates, and none of the remaining positions gives preference to female candidates. Therefore, the result of AI algorithms remaining embedded in existing social structures is to exacerbate this inequality.

How can we resist algorithm bias?

It is necessary to consider the bias of the data first. The operation of the algorithm model is based on data, and the results of the algorithm can be modified with representative and objective data. The lack of female data in the primary data set has led to the gradual marginalization of female users on the Internet, and the collection and supplementation of female data will facilitate the effectiveness of the application of Internet algorithms. Algorithmic data is not necessarily representative and comprehensive, but the use of one-sided data for processing is bound to produce unfair decisions. Data needs to be monitored and reviewed more strictly, and regulators can use legal and administrative means to intervene and improve the transparency of algorithms. For example, for data filing to be reviewed, companies need to predict and explain how this data will be used.

Figure 4. The Gender Imbalance in AI Research Across 23 Countries (Mantha & Hudson, 2018).

In order to improve the gender bias in algorithms, it is essential to increase the proportion of female practitioners and management decision-makers in the AI algorithm field. According to Young, et al. (2021), globally, 78% of professionals in AI are men and, 22% are women. Therefore to promote the current problem of algorithmic bias, it is imperative to improve the perception of algorithmic bias among current practitioners. There is also a need to urge algorithm designers to proactively test and build models to meet the current goals of social development. Network platforms and companies should proactively monitor the operation of algorithms.

Conclusion

Algorithmic bias does not occur independently. In the important machine learning process, unbalanced data sets, biased feature selection and subjectivity caused by artificial labels all interact with each other. In the migration from real social information to data, the potential legitimacy and concealment of bias in algorithms have been constantly practiced and amplified. Biased data continues to be used, such as on Chinese job boards, where data leads to algorithmic bias that deepens discrimination against women in the labour market. At the same time, the social power structure brings uncertain factors to the algorithm, and the influence of capital and traditional power makes the public unable to realize that their cognition and behaviour are controlled by the algorithm. For algorithm governance, it is necessary to cooperate with the society, the judiciary, the government and other aspects of formulating rules, strengthening the review of data, urging enterprises to take more responsibilities and improve the platform’s own algorithm. To prevent the perpetuation of society’s inherent biases and discrimination, we now have to face the challenge of avoiding the misuse of algorithms and technologies.

References

Burke, R., Sonboli, N. & Ordonez-Gauger, A. (2018). Balanced neighborhoods for multi-sided fairness in recommendation. Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, 81, 202–214.

Crawford, K. (2021). The Atlas of AI: Power, Politics, and the Planetary Costs of Artificial Intelligence. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Danks, D. & London, A. J. (2017). Algorithmic Bias in Autonomous Systems. Proceedings of the 26th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence,4691–4697. https://doi.org/10.24963/ijcai.2017/654

GSMA Intelligence. (2020). The Mobile Gender Gap Report 2021. Retrieved from https://data.gsmaintelligence.com/research/research/research-2021/the-mobile-gender-gap-report-2021

Hu, M. (2021, September 28). Study finds gender bias present in artificial intelligence algorithms. SHINE. Retrieved from https://www.shine.cn/news/metro/2109285727/

Jiang, R., Chiappa, S., Lattimore, T., György, A., & Kohli, P. (2019). Degenerate Feedback Loops in Recommender Systems. Proceedings of the 2019 AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society, 383–390. doi: 10.1145/3306618.3314288

Kuhn, P. and Shen, K. (2013). Gender discrimination in job ads: Evidence from china. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 128(1), 287–336. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjs046

Madgavkar, A. (2021, April 7). Conversation on artificial intelligence and gender bias. McKinsey & Company. Retrieved from https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/asia-pacific/a-conversation-on-artificial-intelligence-and-gender-bias

Mikkelso, S. (2021, July 1). Gender Bias in Data and Tech. Geek Culture. Retrieved from https://medium.com/geekculture/gender-bias-in-data-and-tech-ba25524295d4

Mishra, A., Mishra, H., & Rathee, S. (2019). Examining the presence of gender bias in customer reviews using word embedding. (Working paper). David Eccles School of Business, University of Utah. Available at SSRN https://ssrn.com/abstract=3327404

Noble, S. U. (2018). Algorithms of Oppression: How search engines reinforce racism. New York: New York University.

Parikh, N. (2021, October 14) . Understanding Bias In AI-Enabled Hiring. Forbes. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbeshumanresourcescouncil/2021/10/14/understanding-bias-in-ai-enabled-hiring/?sh=5a60c9527b96

Pasquale, F. (2015). The Black Box Society: the secret algorithms that control money and information. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Rambachan, A. & Roth, J. (2019). Bias in, bias out? evaluating the folk wisdom. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1909.08518

Sonboli, N., Smith, J., Cabral Berenfus, F., Burke, R. & Fiesler, C. (2021), Fairness and

transparency in recommendation: The users. Perspective. UMAP ’21: 29th ACM Conference on User Modeling, Adaptation and Personalization, 274–279. doi: 10.1145/3450613.3456835

Young, E., Wajcman, J. & Sprejer, L. (2021). Where are the Women? Mapping the Gender Job Gap in AI. The Alan Turing Institute. Retrieved from https://www.turing.ac.uk/research/publications/report-where-are-women-mapping-gender-job-gap-ai

Zhang, S. (2021). Measuring Algorithmic Bias in Job Recommender Systems: An Audit Study Approach.

Image references

Mantha, Y. & Hudson, S. (2018). The Gender Imbalance in AI Research Across 23 Countries [Image]. Element AI. Retrieved from: https://medium.com/element-airesearch-lab/estimating-the-gender-ratio-of-ai-researchers-around-the-world81d2b8dbe9c

Stauffer, B (2018, April 23). “Only Men Need Apply”Gender Discrimination in Job Advertisements in China. Human Rights Watch. Retrieved from https://www.hrw.org/report/2018/04/23/only-men-need-apply/gender-discrimination-job-advertisements-china

Zhang, Y. & Huang, T. (2020, June 17). The gender gap in labor force participation is widening in China while narrowing in other parts of the world [Image]. PIIE. Retrieved from https://www.piie.com/research/piie-charts/gender-gap-labor-force-participation-widening-china-while-narrowing-other-parts