Introduction

The mechanism of toxic technocultures integrates user practices, cultural values, and political preferences into social media platforms as a new form of racism (Gillespie, 2010), where hate speech and extremism are enacted through unequal forms of online governance, as well as developing within undefined and irresponsible policies (Matamoros-Fernández, 2017).

In addition, social media platforms, as a widely disseminated, modernized, and functionalized cyberspace, provide a large and inclusive venue for free expression (Whittaker, Looney, Reed & Votta, 2021). Online platforms such as Youtube, Facebook, and Twitter influence democratic discourse and public participation by increasing their personalized content, algorithmic recommendations, and political orientation, promoting the possibility of users being misled by extreme content which fuels the proliferation of hate speech and extremist discourse, and weakening orderly civic discourse (Vīķe-Freiberga et al., 2013).

The majority of ‘toxic environments’ are contributed by the computational logic, governance structure, and website design used to build the platform (Massanari, 2017). In other words, the designers and managers of the platform actively pursue and endorse the cultivation of a ‘toxic culture’ conducive to hate speech and extremists’ display, which entails technical politics, subjective discrimination, ingrained prejudice, and hostile tendencies that underpin each platform algorithm.

This article will discuss the internal algorithm design and policy construction of YouTube, a videos-content platform that engages in ‘hate speech’ as demonstrated by the implicit content governance, algorithmic policy, and management mechanisms that sustain its toxic culture (Massanari, 2017).

YouTube as a platform for Racism hate speech

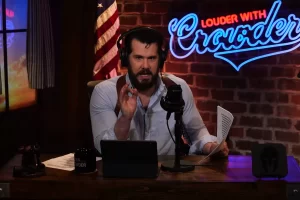

Steven Crowder’s YouTube channel (the verge, 2021)

YouTube, where politicized speech and extreme political activism are accelerating as a result of the platform’s policy of silence. White supremacists and extremist advocates, in particular, are propagating their poisonous and radical political views to a broader audience. The irony is that YouTube platforms make decisions that consistently disadvantage vulnerable communities (Lewis, 2020).

Following several inappropriate and overtly racist statements made by Steven Crowder against black farmers, a YouTube spokesperson stated that this video did not violate the company’s hate speech policy (Peters, 2021). This means that the YouTube definition of hate speech is ‘as long as you don’t express actual hatred for them, you’re free to utilize sarcasm and make jokes about their race’ (Peters, 2021), which means that hate speech does not have to be ‘inciting hatred’ to constitute a policy violation.

Rather, Youtube’s use of ‘humor’ or ‘funny’ forms to moderate and cover-up prejudice amplified on YouTube and racist behavior (Matamoros-Fernández, 2017), implying that the internal logic of white supremacy and racism is buried in YouTube platform policy, as well as its racism, white identity, and discourse against the prevailing nationalism are dominated by the platform’s culture, empowering rights, indigenous pride and liberal ideology (Hallinan & Judd, 2009).

Indeed, YouTube has made a point of providing infrastructure for far-right groups despite its promotion as a platform for ‘free speech’. YouTube enhances white supremacist influencers to a broader audience through viewing, sharing, subscriptions, and advertising revenue (Ganesh, 2021). Thus, the platform becomes an amplifier and producer of racism, replicating racist social institutions via their affordances and internal machine-processed to reinforce and distribute its ‘toxic ideology'(Streeter, 2011).

The case of extreme racism on YouTube

In 2019, a white supremacist shooter opened fire on mosques and the Lynwood Islamic Centre in Christchurch, New Zealand, killing 51 people. He is a YouTuber who generates extreme content and even live streams parts of his attacks. There have been no algorithmic adjustments or new restrictions implemented by YouTube to address potential terrorism and hate speech, such as policing and removal of illegally violent content (Whittaker et al., 2021); it has also not made a firm commitment to protect Muslim content creators and users or to enact clear regulations prohibiting the spread of Islamophobia on YouTube.

However, the reality is that hate speech continues to be ubiquitous, and YouTube continues to give white supremacist groups special treatment (Ganesh, 2021). YouTube still prioritizes the goal of getting people to watch more videos (De Vynck, 2021), and strives to get as many as possible by promoting controversial content despite the fact that it has the capacity to impose stricter constraints on purveyors of severe hate speech. YouTube declared that it defends the right to “undesirable” opinions — which serves as the framework for concealing racism and professing to safeguard the freedom of expression exclusively for “white males” dominate groups (Matamoros-Fernández, 2017).

Extremist content online: videos from New Zealand shooting remain online (counter-extremism, 2019)

The mechanism of the YouTube community

Indeed, how users interact with the platform, how the material is distributed, and how user-generated content is handled all have an impact on the design of the rules inherent inside the YouTube platform (Moore & Tambini, 2021). When a user enters a keyword or topic with a specific tag into a search engine, the algorithm recommendation automatically identifies and guides the user to enter relevant content pages, which also places them in the reality filter bubble; that is, the same user is directed to a similar topic page, and forwarding enhances the feeling of ‘the online space is the world’ through sharing, likes, and subscribing mechanisms, thereby strengthening the connection for communicative purposes within the YouTube community.

For instance, Ben Shapiro, a prominent conservative political commentator in the United States, asserts that more than half of the world’s Muslims have become radicalized. He contended that the essence of Islam is immaterial (Greenberg, 2014), that its underlying beliefs advocate violence, and the extremists constitute the majority of the Muslim community. When he implies that the majority of Muslims are radicals, he is referring to radicalism and actual terrorists in Sharia-law countries such as Pakistan, and particularly when he claims that “Islamophobia is a completely rational concern” (Lewis, 2020), he is obviously associating Islam with radicalism. His approach to side-scrolling speech has an effect on persons who have ulterior motives – that is, those who make statements that are not blatantly insulting or discriminatory toward a certain group. However, encoding and decoding its subtle indicators and indirect remarks in intricate syntax, reveals that many of those people’s disputed speech appears to be inappropriate, and remains hate speech.

In addition, viewers are more likely to watch those contents, and argue about whether such an utterance is applicable and acceptable, as well as viewing for similar video content to support their points of view after watching the ‘implicit discrimination’ speech content; furthermore, they may even click on more YouTube videos with the same substance, such as those generated by conspiracy theorists, influencers, commentators and politicians who share with the parallel ideas and disputed political standpoints. Therefore, the mechanisms on YouTube exhibit the speed and potency of online public dialogue in the context of broad algorithmic recommendations.

As a result, YouTube’s algorithms management and content approval procedure virtually govern online discussions while attracting a wider audience who consumes relevant content through the networked video-media marketplace (Ardia, Ringel, Ekstrand & Fox, 2020). In response to a multi-layered market of diverse consumers, the racist platform on YouTube appears to be developed and cultivated for the purpose of growth and profit maximization (Gillespie, 2010; Rieder & Sire, 2013). Thus, YouTube prioritizes those content that is contentious without jeopardizing its ‘bias nature’, while generating more implicit discrimination and stereotype substances for consumption via recommendation systems and algorithmic mechanisms, and expanding more users’ access to it.

The online governance on YouTube

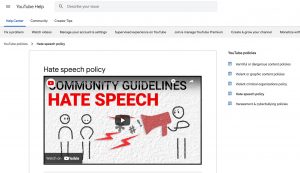

YouTube Community Guideline (google, 2022)

Social media platforms are subjected to a variety of user interactions, which continue to erode the platform’s immunity as they spread (Woods, 2012). The regulatory approach is determined by the platform’s operation and is influenced by the platform’s scale, multinational character, acceptable online environment, as well as the traditional manner of media-based regulation methods (Ofcom, 2018, 25-26). Moreover, the platform learns from each online harm to provide additional guidelines for preventing and avoiding distressing events. YouTube defines its internal scope for hate speech in detail and provides specific examples through its community guidelines and terms; however this is not a standard answer formulated through terms (Moore & Tambini, 2021); rather, the reality we are confronted with is constantly changing and contains complex, diverse, tricky, and dangerous real-world hate speech cases.

The guidelines formulated and developed by the YouTube company to establish the platform are not neutral. YouTube employs cognitive biases to compel users into adopting established behaviors (Costa & Halpern, 2019), and each user’s rationality and autonomy will be impaired and exploited by algorithmic design choices within a video content-dominated procedure (Leiser, 2016). Indeed, the majority of viewers are reasonable, they only are easily manipulated by dominant emotions, swayed by specific events, and overwhelmed by sudden and powerful subjective utterances; and the applicable regulatory system gives the go-ahead to maximize benefits and encourage users to create more contentious content in order to further the goal of maximizing revenue (Zuboff, 2015).

Furthermore, the complaint system and deletion procedure within the platform have a subtle impact on the construction and generation of users’ online improper behavior. According to YouTube’s community guidelines, the platform will remove corresponding content based on the publication and dissemination of hate speech, as well as penalize associated channels by limiting or prohibiting access to the video, locking the user’s account, and among other measures to combat online hate speech. YouTube, on the other hand, notes that misusing the rules would undermine the voices that thrive on the platform (Patell, 2021). YouTube’s vision and purpose are encapsulated in an early speech given in response to a request to handle harmful content, namely ‘giving everyone the right of a voice’. Moreover, YouTube strongly opposes obligatory surveillance, claiming that it may disproportionately restrict users’ freedom of speech, impose an unnecessary cost on service providers, and impede their capacity to conduct business freely (Patell, 2021). Apparently, the precondition for framework oversight on YouTube appears to be avoiding interfering with the transmission and circulation of information, as well as preventing stifling the flow of ideas and opinions required in a democratic society. However, this precisely reveals that this seemingly valid content generates controversy, debate, and disagreement, as well as upsetting marginalized and minority populations.

As a platform with a monopoly on the Internet video market, YouTube is accountable for enacting public-interest restrictions and developing a filtering process that preserves free speech (Karan, 2018). Nevertheless, the majority of independent media individuals, journalists, and spokespersons who are compelled to upload videos on YouTube in order to earn additional incomes with educational and news-oriented media programming that inexorably includes hate subjects but makes no attempt to demonstrate this further are banned, assessed, and utilized, based on the company’s community guidelines. While many other videos with ‘worse’ content remain unpunished, this highlights how YouTube evaluates various accounts differently. YouTube’s application of double standards in dealing with all of the hate speech they encountered demonstrates that the greatest impediment to free expression, and hate speech, is on the individuals, not on regulations or anything else.

As a result, the platform’s complaint process is particularly context-sensitive, avoiding arbitrary removals and flagging caused by excessive operations. YouTube emphasized that the majority of content flags it received on a daily, do not pertain to illegal content, but rather represented the opinions of individuals who object to the relevant content (Patell, 2021). Therefore, YouTube’s internal complaint and regulation processes prioritize preserving human rights and freedom of expression, while also extending opportunities and perspectives for profit-driven dominant organizations.

Conclusion

Social media platforms generate relevant data and content as a result of their involvement in digital information systems, provision of critical services and algorithmic mechanisms, and exercise of control over their technology, architecture, and operational processes (Roberts, 2019).

Technology is never neutral, and the hate speech disseminated across on multiple platforms reveals the algorithmic underpinnings of these platforms, reflecting both their designers’ inherent hatred and the broader socio-technical structure. The malignant structures of ‘capital accumulation,’ ‘power system,’ ‘culture marginalization,’ and ‘interest first’ are also illustrated within such social and technological contexts (Roberts, 2019).

The governing authority manipulates and evaluates the content domain and moderation mechanism, paving the path for a more accessible and aesthetically appealing networked platform (Roberts, 2019). When we as consumers choose to engage with these media outlets and become immersed in their internal operations, we are essentially expressing our own viewpoint, preferences, and ideals, as well as projecting social logic, ideology, and cultural imagination (Roberts, 2019).

Reference list:

Ardia, D. S., Ringel, E., Ekstrand, V., & Fox, A. (2020). Addressing the decline of local news, rise of platforms, and spread of mis- and disinformation online: A summary of current research and policy proposals. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3765576

Costa, E., & Halpern, D. (2019). ‘The Behavioural Science of Online Harm and Manipulation, and What to Do about It’. https://www.bi.team/publications/the-behavioural-science-of-online-harm-andmanipulation-and-what-to-do-about-it/.

De Vynck, G. (2021, April 6). YouTube says it’s getting better at taking down videos that break its rules. They still number in the millions. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2021/04/06/youtube-video-ban-metric/

Gillespie, T. (2010). The politics of ‘platforms’. New Media & Society, 12(3), 347–364. doi:10.1177/1461444809342738

Greenberg, J. (2014, November 5). Ben Shapiro says a majority of Muslims are radicals. (n.d.). @politifact. https://www.politifact.com/factchecks/2014/nov/05/ben-shapiro/shapiro-says-majority-muslims-are-radicals/

Ganesh, B. (2021, March 16). Platform Racism: How Minimising Racism Privileges Far-Right Extremism. https://items.ssrc.org/extremism-online/platform-racism-how-minimizing-racism-privileges-far-right-extremism/

Hallinan, C., & Judd, B. (2009). Race relations, indigenous Australia, and the social impact of professional Australian football. Sport in Society, 12(9), 1220–1235. doi:10.1080/17430430903137910

Karan, D. (2018, October 08). How exposing hate speech landed a YouTube news channel in trouble. (n.d.). The Wire. https://thewire.in/rights/youtube-hate-speech-pal-pal-news

Lewis, B. (2020, December 14). I warned in 2018 YouTube was feeling far-right extremism. Here’s what the platform should be doing. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2020/dec/11/youtube-islamophobia-christchurch-shooter-hate-speech

Leiser, M. (2016). ‘The Problem with ‘Dots’: Questioning the Role of Rationality in the Online Environment’. International Review of Law, Computers, and Technology 30: 191–210.

Moore, M., & Tambini, D. (2021). Regulating big tech: Policy responses to digital dominance. Oxford University Press.

Massanari, A. (2016). #Gamergate and The Fappening: How Reddit’s algorithm, governance, and culture support toxic technocultures. New Media & Society, 19(3), 329–346. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444815608807

Matamoros-Fernández, A. (2017). Platformed racism: the mediation and circulation of an Australian race-based controversy on Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube. Information, Communication & Society, 20:6, 930-946. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118x.2017.1293130

Moore, M. (2018). Democracy Hacked: How Technology Is Destabilizing Global Politics. Oneworld Publications.

Ofcom. (2018, September 18). ‘Addressing Harmful Content Online: A Perspective from Broadcasting and On-Demand Standards Regulation’.

Peters, J. (2021, March 18). Inexplicably, YouTube says extremely racist Steven Crowder video isn’t hate speech. The Verge. https://www.theverge.com/2021/3/18/22339030/youtube-racist-steven-crowder-video-does-not-violate-hate-speech-policies

Patell, J. (2021, November 5). Our shared responsibility: YouTube’s response to the government’s proposal to address harmful content online. Google. https://blog.google/intl/en-ca/products/inside-youtube/our-shared-responsibility-youtubes-response-to-the-governments-proposal-to-address-harmful-content-online/

Roberts, S. T. (2019). Behind the Screen: Content Moderation in the Shadows of Social Media. New Haven: Yale University Press. https://doi-org.ezproxy.library.sydney.edu.au/10.12987/9780300245318

Rieder, B., & Sire, G. (2013). Conflicts of interest and incentives to bias: A microeconomic critique of Google’s tangled position on the Web. New Media & Society, 16(12), 195–211. doi:10.1177/1461444813481195

Streeter, T. (2010). The net effect: Romanticism, Capitalism, and the Internet. New York: New York University Press. https://doi.org/10.18574/nyu/9780814741153.001.0001

Vīķe‐Freiberga, V., Däubler-Gmelin, H., Hammersley, B., & Maduro, L. M. P. P. (2013). A Free and Pluralistic Media to Sustain European Democracy [Report]. EU High-Level Group on Media Freedom and Pluralism.

Whittaker, J. & Looney, S. & Reed, A. & Votta, F. (2021). Recommender Systems and the amplification of extremist content. Internet Policy Review, 10(2). https://doi.org/10.14763/2021.2.1565

Woods, L. (2012). ‘Extension of Journalistic Ethics to Content produced by Private Individuals’. In Freedom of Expression and the Media, 141–168. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers.

Zuboff, S. (2015). ‘Big Other: Surveillance Capitalism and the Prospects of an Information Civilization.’ Journal of Information Technology 30: 75–89.