Source: Nyome (2020)

Source: Nyome (2020)

Introduction

With the development of online information technology, social media is penetrating our daily life quietly and rapidly. The direction of media communication has shifted to two-way communication, with participatory media empowering audiences to interact and collaborate while enabling the public to become more open (Flew 2008, p. 30). The algorithm is at the core of the platform’s operation. However, acting as cultural mediators and tools for anti-social purposes, algorithms are not neutral and biased (Matamoros-Fernández, 2017, p. 934).

Instagram’s pushing of information to users may be biased in terms of racial and gender stereotypes (Ghaffari, 2022, p.163). Such inequality is caused by the digital literacy gap and the low visibility caused by algorithms (Introna & Nissenbaum, 2000). Arguably, the non-neutrality principle of algorithms provokes much prejudice, creating a divide between social groups and attacking inclusion and diversity.

This blog will analyse the case of Nyome Nicholas-Williams(@curvynyome), a black plus-size model. Her photos posted on Instagram were removed by the platform’s algorithm, sparking the #iwanttoseenyome campaign and making Instagram change its nudity policy. This example illustrates the hidden bias of Instagram’s moderation algorithm – the censorship of black bodies reflects the inequality of discourse rights in social media, provoking a discussion that the algorithm reinforces social bias and considers three ways to reduce such inequalities.

Bias on Instagram’s Algorithm

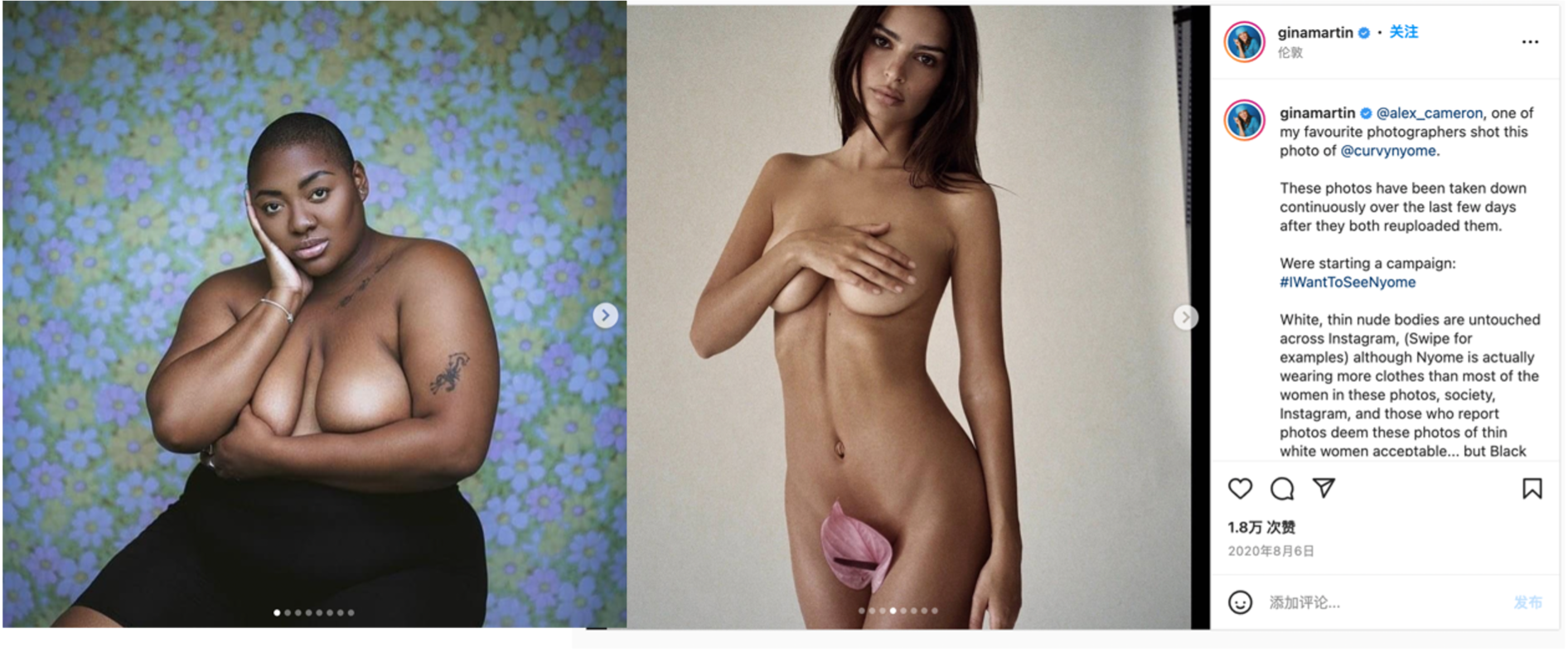

In July 2020, Nyome posted a series of photos on Instagram in collaboration with the photographer Alex Cameron. One of the pictures showed her sitting on a chair with her arms around her topless body, but it was removed because it allegedly “violated community rules on semi-nudity and sexual activity”. After frequent censorship, Nyome immediately criticised the platform and its biased algorithm publicly (Image 1).

Image 1: Screenshot of Nyome’s criticised post (Nyome, 2020)

Algorithms Reinforce the Sense of Racial Bias

Why does this community ordinance against ‘squeezing breasts’ frequently apply to black plus-size female models rather than thin white women?

Firstly, Instagram’s content review mechanism is complicated and fluid (Olszanowski, 2014, p. 84), employing algorithms and humans to judge the community’s content. However, the algorithmic principle is neutral, the practical algorithm application not neutral. In content review, data-centric technologies are radically contradictory (Gillespie 2020, p. 2), and platforms amplify racism through mandates, policies and algorithms. The cascading of content ensures platforms’ compliance with norms and operational regulations, but the workload and complexity of sorting through redundant platform information are far beyond the capacity of the algorithms (Robert, 2019, p. 34). In other words, social networks’ infrastructures tend to harm and censor their most vulnerable users. Such online platforms excessively rely on automated judgements that can be fraught with bias or something destructive (Pasquale, 2015, p. 18).

Indeed, this double standard of censorship reflects that Instagram’s regulations reinforce the ‘hegemonic process of promoting the legitimisation of social order’ (Olszanowski, 2014, p. 840), excluding users by colour and gender. The platform’s content review is fluid, and rules enforcement is arbitrary to some extent (Gillespie, 2017). The algorithm design can be embedded with the subjective intentions of designers and developers. Therefore, the automated decisions made by the algorithm are the results sought by the users of the algorithm design as well. Compared with the traditional construction of reality in mass media, Instagram’s algorithm generates low transparency in collaboration with users (Just & Latzer, 2017, p. 253). The covert nature of the algorithm makes it almost difficult for Instagram users to detect the hidden manipulation behind the algorithm or even to determine their algorithmic discrimination experience. Nyome mentioned that she did not understand why Instagram repeatedly deleted her photos.

Unbalanced Power Dynamics

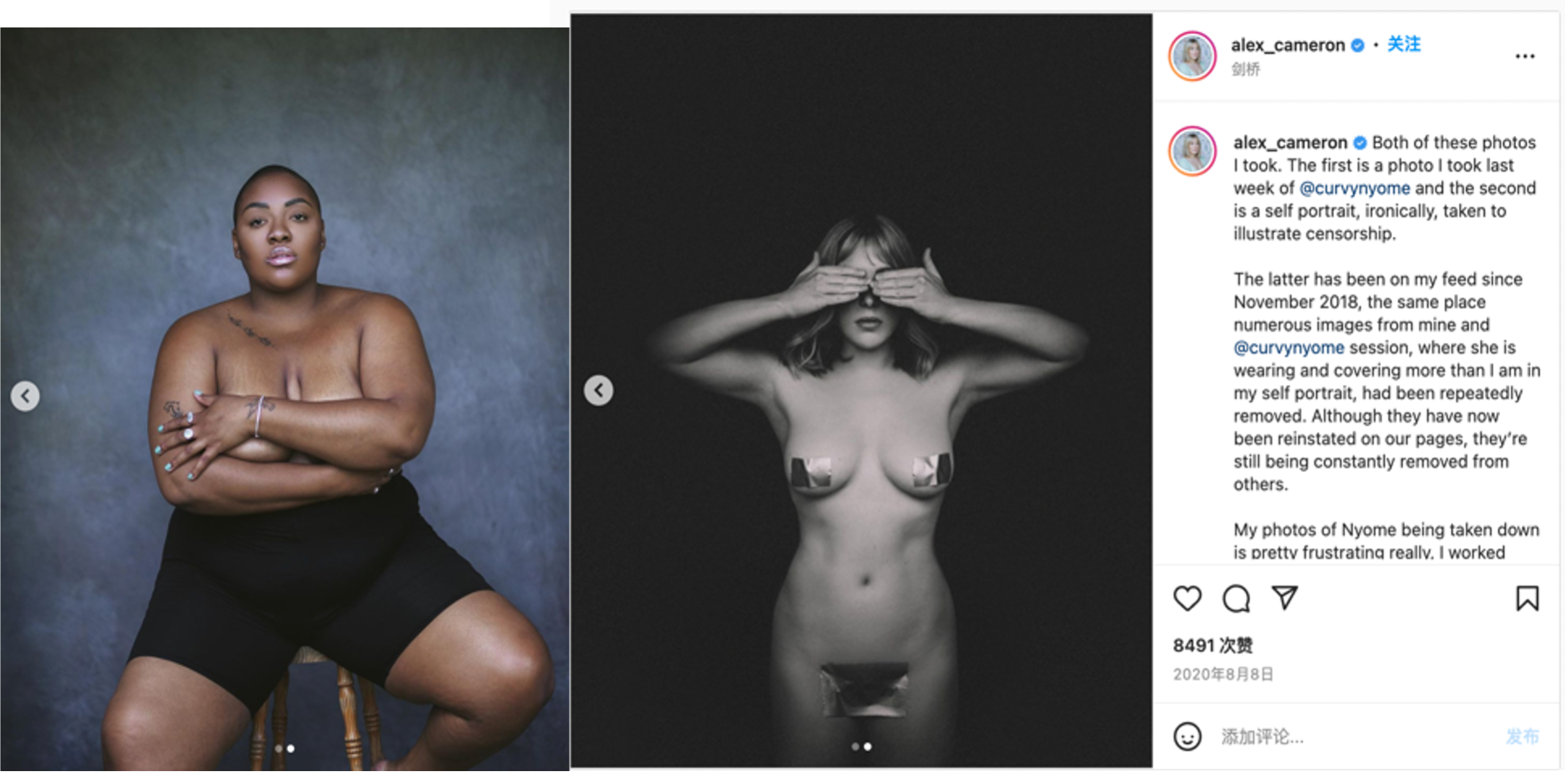

Gina Martin (@ginamartin), one of the #iwanttoseenyome campaigners, posted in solidarity with Nyome on Instagram (Image 2). She pointed out that Nyome’s pictures were constantly being removed after reupload. To back up her statement, Martin used several nude images of white, thin people that the Instagram community had censored. She also indicated that black women with larger bodies were constantly accused of violating community rules. Based on Martin’s example, a picture showing a non-white person in a thin state is likely to break community rules for posting nudity.

Image 2: Martin’s post image to prove her argument(Martin, 2020)

Image 2: Martin’s post image to prove her argument(Martin, 2020)

Alex Cameron (@alexcameron), a photographer who regularly takes photos of Nyome, has gone along with testing the Instagram censorship algorithm as well. Cameron’s post contains two images, a body shot of Nyome she photographed and a nude body picture of herself, with the photographer covering less cloth than Nyome(Image 3).The irony of this result is that the result of both images’ comparison enables people to feel strongly exclusive, despite the platform’s commitment to consistency in content review.

Image 3: Cameron’s post, comparison between Nyome and her nude body(Cameron, 2020)

Image 3: Cameron’s post, comparison between Nyome and her nude body(Cameron, 2020)

In accordance with both campaigners, there is unexplainable and subtle bias in the Instagram algorithm, and this inaccurate vetting places a false burden on disenfranchised and minority groups (Gillespie,2020, p. 3). Whether such regulations are intentional or not, Instagram inevitably constructs a vehicle for transmitting prejudice that protects whiteness and imagines the ideal subject as white (Matamoros-Fernández,2017, p.934). This partly or indirectly reflects social differences, as algorithms extend the social discrimination of the natural human world. The ease of access to information vehicles like social media seems to allow equal access to information and expression between individuals and communities, but it triggers more profound inequalities.

Instagram’s community censorship rules are rife with subjective bias against plus-size users, especially people of colour. People who formulate the censorship rules may not think the same way as those labelled as the ‘other’. Meanwhile, users of the platform have no way of confirming how the images posted were vetted, or whether the algorithm or the platform’s reviewers were involved in identifying ‘nudity’. The answer to this is still unknown. Undoubtedly, the aggregated nature of social media exacerbates discrimination, affects groups’ social inclusion and infringes on the public’s right to equality. Using unclear censorship regulations for content governance on such platforms reproduces inequalities (Matamoros-Fernández, 2017, p. 936)

The Success of the #iwanttoseenyome Movement

In the context of Web 2.0, social media has given more voice to various groups of people, and the power to speak is no longer held by a few “elites” but by the public. To maintain their corporate images and commercial profits, media platforms are actively regulating controversial content (Matamoros-Fernández, 2017, p. 936).

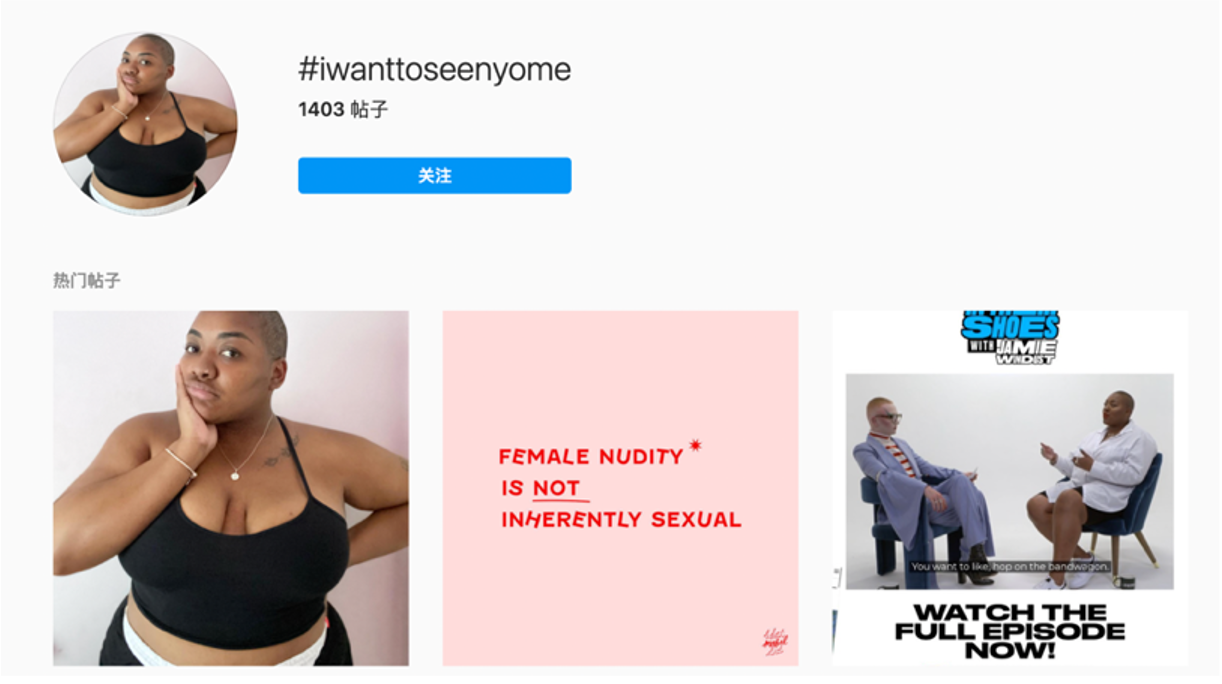

Thankfully, supported by many users, Nyome’s experience has led to the #Iwanttoseenyome movement. Social platforms have shaped the way the public lives and organises society. In the context of digital media, the rights of the public interact with the power of platforms comprehensively, mutually exploiting and facilitating each other to a certain extent. Launched by Nyome and other activists in August 2020, the campaign organised around the hashtag #iwanttoseenyome aims to call on all groups of black women whom the Instagram algorithm has discriminated against to join the fight that attaches the hashtag to their social media posts to raise social awareness. The campaign has received over 1,400 responses so far(Image 4).

Image 4: #iwanttoseenyome hashtag on Instagram(Instagram, 2020)

Image 4: #iwanttoseenyome hashtag on Instagram(Instagram, 2020)

As part of the recommendation algorithm, hashtags are used to algorithmically push messages precisely, allowing the campaign’s social impact to grow, and the immediacy and interactivity of new media help create greater control over the discourse. While Instagram sparked this social movement, it was also the medium of cultural communication for the #iwanttoseenyome movement that supported the idea that technology is both the problem and the solution (Just & Michael, 2017, p. 253). In other words, it gives disadvantaged groups subject to discursive repression the opportunity to break the hegemonic grip of discourse and helps achieve equal opportunities between various groups. Changes in technological infrastructures and policy responses to the demands of public opinions increasingly call for changes in the platform content management (Gillespie, 2017).

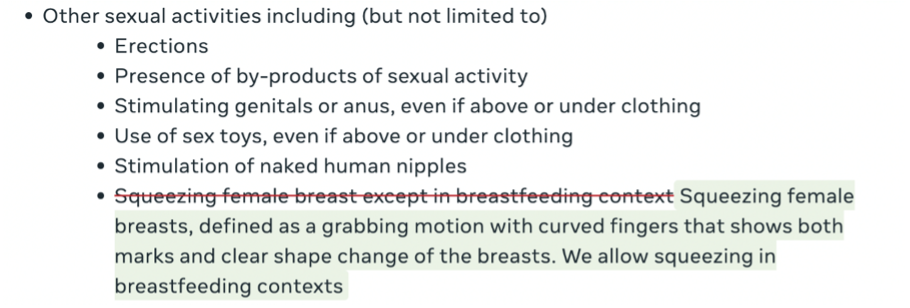

Designing technology to avoid bias can be challenging, but the ability to re-address such bias is the first step in fighting discrimination. Therefore, Adam Mosseri, Head of Instagram, has changed its policy on nudity to distinguish between sexual and non-sexual breasts in images, to dispel rumours of discrimination and ensure that all body types, including the black plus size, are treated equally on the platform. In accordance with the initial unclear rule of ‘no breast squeezing except for breastfeeding‘ (Image 5), users were allowed to post content that only included hugging, cupping or breast holding from 28 October 2022 (Meta, 2020). The policy does not clarify the reason for the difference in vetting posts between thin white women and black plus-sized women. Instagram has successfully shifted the discourse from racial bias to helping users be more disciplined in their self-presentation and self-documentation on the platform.

Image 5: Nude photo Policy change on Instagram(Meta,2020)

Image 5: Nude photo Policy change on Instagram(Meta,2020)

How can similar incidents of censorship inequality be reduced?

While Nyome has gained a relatively fair voice, countless marginalised groups are still in the new media. Therefore, how can we construct a more equal discursive space?

The Algorithm as a Solution

Governing algorithmic discrimination through technology may be a way to create a fair online discourse space. Despite extreme care to avoid inaccuracies, algorithmic discrimination may exacerbate existing bias in society, which can be attributed to constant reconfiguration based on past input and output data. Nevertheless, it is possible that algorithmic regulatory systems can be imagined and designed in more egalitarian and progressive ways in terms of value, orientation and operation (Reddy et al., 2019,p.6). Furthermore, it is essential to clarify the subject of accountability for algorithmic discrimination, with the algorithm compilers shouldering primary responsibility if the algorithm contains discriminatory content. Also, the inputters should be responsible if they have discriminatory operations that cause algorithmic discrimination consequences during data selection and collection. In the case of the US Algorithmic Accountability Act of 2019, a more productive solution is reached by asking about the structure of embedded accountability rather than pursuing the question of who did it (Reddy et al., 2019, p. 6).

Promoting Diversity in Algorithm Teams

A shortage of diversity in AI teams and leaders can cause discrimination against disadvantaged, minority and protected groups. A diverse team is essential for effective negotiations at the AI development and deployment level to regulate development practices and curb unconscious expressions of bias(Akter et al., 2021, p.3). Instagram teams should be interdisciplinary, and they need people of different gender, various ethnic and socioeconomic backgrounds as well as disabled and sexual orientation groups who are better able to detect existing biases.

Developing Clear Technical Fairness Guidelines

Social laws, regulations, institutions and judicial decision-making practices are governed by procedural justice. These regulations are written into platforms in the form of code. However, programmers may not realise the technical implications of fairness and lack some necessary technical fairness rules to guide their programming. For instance, Google introduced a way to measure and prevent discrimination based on data-sensitive attributes in artificial intelligence design (Hardt, 2016). For Instagram, content reviewers should follow a transparent, independent fairness principle to reduce discrimination arising from individual subjectivity.

In Conclusion

Online platforms like Instagram influence the construction of users’ real life, but discrimination is magnified exponentially by algorithmic bias. Consequently, we need to confront algorithmic prejudice and recognise the following two aspects. On the one hand, it is inevitable, coming from the human tendency, of which implicit bias is predominant; on the other hand, algorithmic bias is identifiable. While the vetting mechanisms of platforms are prone to discrimination, the flattening and decentralisation of online communication have brought some discursive power to marginalised groups. However, algorithmic bias remains an unprecedented challenge for all of humanity. It is essential to build an equal voice for users on social platforms by enhancing the clarity of algorithmic rules. To defeat this invisible gatekeeper, it is necessary to have improved algorithmic oversight mechanisms, fair technical guidelines and diverse team building.

Reference:

Akter, McCarthy, G., Sajib, S., Michael, K., Dwivedi, Y. K., D’Ambra, J., & Shen, K. . (2021). Algorithmic bias in data-driven innovation in the age of AI. International Journal of Information Management, 60, 102387–. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2021.102387

Flew, T. (2008) New Media: An introduction (20 key new media concepts: pp.21-37), Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ghaffari. (2022). Discourses of celebrities on Instagram: digital femininity, self-representation and hate speech. Critical Discourse Studies, 19(2), 161–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405904.2020.1839923

Gillespie, T. (2017). Governance of and by platforms. In J. Burgess & T. Poell (Eds.), The Sage hand- book of social media. Sage. Pre-Publication Copy. Retrieved from http://culturedigitally.org/wp- content/uploads/2016/06/Gillespie-Governance-ofby-Platforms-PREPRINT.pdf

Gillespie, T. (2020). Content moderation, AI, and the question of scale. Big Data & Society. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951720943234

Hardt, M. (2016). Equality of Opportunity in Machine Learning [Website]. Google AI Blog. http://ai.googleblog.com/2016/10/equality-of-opportunity-in-machine.html

Introna, L. D., & Nissenbaum, H. (2000). Shaping the web: Why the politics of search engines matters. The Information Society, 16, 169–185. doi:10.1080/01972240050133634

Just, N., & Latzer, M. (2017). Governance by algorithms: Reality construction by algorithmic selection on the Internet. Media, Culture & Society, 39(2), 238–258. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443716643157

Matamoros-Fernández, A. (2017). Platformed racism: The mediation and circulation of an Australian race-based controversy on Twitter, Facebook and YouTube. Information, Communication & Society, 20(6), 930–946. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2017.1293130

Meta. (2020). Adult nudity and sexual activity | Transparency Centre. Meta. https://transparency.fb.com/en-gb/policies/community-standards/adult-nudity-sexual-activity/

Olszanowski. (2014). Feminist Self-Imaging and Instagram: Tactics of Circumventing Sensorship. Visual Communication Quarterly, 21(2), 83–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/15551393.2014.928154

Pasquale, F. (2015). The black box society. Cambridge: Harvard University Press

Reddy, Cakici, B., & Ballestero, A. (2019). Beyond mystery: Putting algorithmic accountability in context. Big Data & Society, 6(1), 205395171982685–. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951719826856

Image reference:

Cameron, A. [@alex_cameron]. (2020, August 8). Both of these photos I took. [Instagram post]. https://www.instagram.com/p/CDmQyncBxgy/

Nyome, N.W. [@curvynyome].(2020, July 30). Why are white plus sized bodies seen as “acceptable” and accepted and black plus sized bodies not?. [Instagram Post]. https://www.instagram.com/p/CDRUNf9gOvt/

Martin, G.[@ginamartin].(2020,August 6). @alex_cameron, one of my favourite photographers shot this photo of @curvynyome. [Instagram Post]. https://www.instagram.com/p/CDg_bern1ut/